"Hound" - The Scholarly Review IV - The Death of Aife's Only Son

The fourth part to my scholarly review of Paul J. Bolger's dark fantasy graphic novel "Hound"

This installment is the penultimate part of my overall scholarly review for Paul J. Bolger’s Hound. It is a fairly short “chapter” in the graphic novel, but adapts one of my favorite stories from Cú Chulainn’s life and is utilized as a key turning point in this story’s take on the character. The story it takes from is Aided óenfir Aífe (“The Death of Aife’s Only Son”), a ninth century story from the Yellow Book of Lecan,1 which relates the tragic duel Cú Chulainn had with his only son, Conla, whose mother was Aife, the sister of Scathach—Cú Chulainn’s teacher of martial arts.

As usual, this review will contain spoilers for both Hound and the original myths of Cú Chulainn, so if you haven’t read either and want to experience either, consider checking them out before reading on. Also, my previous installments of this review are linked directly below if you haven’t caught up on them yet.

In terms of Aided óenfir Aífe (hereafter AOA)’s place in the “chronology” of the Ulster Cycle, I am unsure of where most scholars place it. In certain collections of Irish myth that include Cú Chulainn’s story, usually editors might place it after the Táin Bó Cúailnge (“The Cattle Raid of Cooley”) sections. If we follow Fergus’ timeline given in TBC, Cú Chulainn goes to Scathach when he is six years old, training with her for a year, and conceiving Conla with Aife in that timespan. Conla comes to Cú Chulainn seven years afterwards,2 which would make Cú Chulainn 14 and Conla only seven years old. My advisor in grad school, Ranke de Vries, pointed out that in the stories dealing with Cú Chulainn’s martial training and relationship with Emer (Tochmarc Emire and Foglaim Con Culann), he may be actually older than six. Mythological heroes also sometimes progress at faster rates than average humans, in terms of skill or physical growth.

This part of Hound begins ten years following the “Cattle Raid of Cooley” events with King Connor and Fergus watching a chariot race and commenting on how Cú Cullan has chosen to live as a farmer at Emer’s estate rather than live among his kingly relatives. A small boat bearing sails emblazoned with Pictish symbols approaches the shore of Ulla, its rider demanding, “Send out your strongest champion!”

In AOA, the introduction of Conla is a little more drawn out and laced with a bit of foreshadowing. The text describes him as approaching in “…a skiff of bronze…and gilt oars in his hand.”3 In the black and white medium of Hound, it is not really clear if Conla’s boat is made of these materials and no character makes mention of it. Given Bolger seems to have gone for a grittier version of this story, it’s unlikely he had it in mind to make Conla’s boat as decked out as it is in the original story. The foreshadowing comes as a bit of a spectacle, which has Conla taking down birds with stones he shoots from his staff-sling (cranntáball in Old Irish) but leaving them alive, “Then he would let them up in the air again.”4 This is likely a reference to the story “Cú Chulainn takes up arms” in “Cú Chulainn’s Boyhood Deeds” where he brings down a flock of swans with his sling without killing them and ties them to his chariot. Conla also performs something that is translated as a “palate-feat” (carpad clis in Old Irish), which the text seems to describe as some sort of vocalization: “He would perform his palate-feat between both hands, so that the eye could not reach it (?) He would tune his voice for them [the birds], and bring them down for the second time. Then he revived them once more.”5 Conchobar comments on the boy’s talent,

“[W]oe to the land into which yonder lad comes!…If grown-up men of the island from which he comes were to come, they would grind us to dust, when a small boy makes that practice. Let some one go to meet him! Let him not allow him to come to land at all!”6

Hound cuts right to Conla landing on the shore and beginning his fight with the Ulster champions, only repeating his line, “Send out your strongest champion!” The first man Connor sends to take care of him is a fighter named Horgan. I imagine this character is just meant to serve as a redshirt, showcasing Conla’s ability to salmon leap like his father as well as his willingness to slay outright. The original text takes its time when it comes to Ulster sending out champions to meet Conla before bringing in Cú Chulainn. The first man sent out by Conchobar is Condere mac Echach (son of Echu) to attempt diplomacy with Conla. When Condere meets Conla and inquires his origin and purpose for coming to Ulster. Conla replies, “‘I do not make myself known to any man…nor do I avoid any man.”7 In the beginning of AOA and after Cú Chulainn’s union with Aife in Tochmarc Emire (“The Wooing of Emer”), he places three geasa on Conla before he is born:

[From AOA:] “Let no man put him off his road, let him not make himself known to any one man, nor let him refuse combat to any.”8

[From TE:] And [Cú Chulainn] said that Conla was the name to be given to him, and told [Aife] that he should not make himself known to anyone, that he should not go out or the way of any man, nor refuse combat to any man.9

Condere attempts to reason with Conla by naming several Ulster champions who might protect Conla if he introduces himself properly, but he refuses. This is again reminiscent of “Cú Chulainn’s Boyhood Deeds” when, at the beginning of that tale, Cú Chulainn refuses protection from the Ulster champions when he goes off to play at Emain Macha. These behaviors are likely meant to signal to the audience that Conla is undoubtedly Cú Chulainn’s son, having inherited not only his talents but his headstrongness as well.

When Condere reports Conla’s resistance to the Ulster champions the hero Conall Cernach volunteers to meet the boy and fight him to preserve the honor of his home province. Conla manages to knock Conall down with a single stone from his sling, humbling that champion enough to call for someone else to take his place.10

In Hound, Cú Cullan is summoned swiftly after Horgan is slain. Emer simply notes Conla's young age and bids her husband to “Go easy” on him. In AOA, Emer more pointedly tells Cú Chulainn the boy on the shore is his son and warns him not to fight:

“Do not go down!” said she. “It is a son of thine that is down there. Do not murder thy only son!…It is not a fair fight nor wise to rise up against thy son….Turn to me! Hear my voice! My advice is good. Let Cuchulinn hear it! I know what name he will tell, if the boy down there is Conla, the only son of Aife…”11

Cú Chulainn ignores Emer’s warning and challenges Conla in order to preserve the Ulster champions’ honor. In Hound, Cú Cullan seems driven to fight mostly because Connor asked him to and Conla’s statement, “[My mother] is who sent me…to take the head of every dog lover on this rock or die trying.” In the stories featuring Conla’s conception, Cú Chulainn openly invites Aife to send their son to him once he is old enough—the marker for that being when a ring gifted to Aife by Cú Chulainn can fit on his thumb.12

In sort of a repeated pattern, Hound also decides to streamline Cú Cullan and Conla’s fight, implanting it with elements of Cú Cullan’s madness induced by the Morrigan. Cú Cullan also makes an aside that Horgan was his friend, although we only ever see him in this chapter. The fight shows them as equally matched, with the salmon leap feat being the most-utilized move between the two. In AOA, it does take a little more time to describe the fight and how Conla’s skills are on par with, or may even surpass Cú Chulainn’s at some points. At the end of Foglaim Con Culainn (“The Training of Cú Chulainn”), after learning of Aife’s pregnancy, he advises her,

“But if it be a son that thou wilt bear, nurture him well, and teach him feats of valour and bravery, and teach him all the feats save only the feat of the gae builg, for I myself will teach that to him after he reaches Ireland.”13

As seen above with Conla’s entrance, he utilizes several feats Cú Chulainn mastered originally. Some of the other feats Conla utilizes includes the “measured blow” feat where he “crops off Cuchulinn’s hair.”14 The two also wrestle each other, with Conla displaying his inherited strength as he mounts a pair of pillar stones to reach his father, and his feet sink into the stones “up to his ankles.”15 The apex of the fight begins when Cú Chulainn and Conla attempt to drown each other, with the latter almost succeeding twice. Cú Chulainn decides to employ the gae bolg to end the fight, dissembowling Conla.16

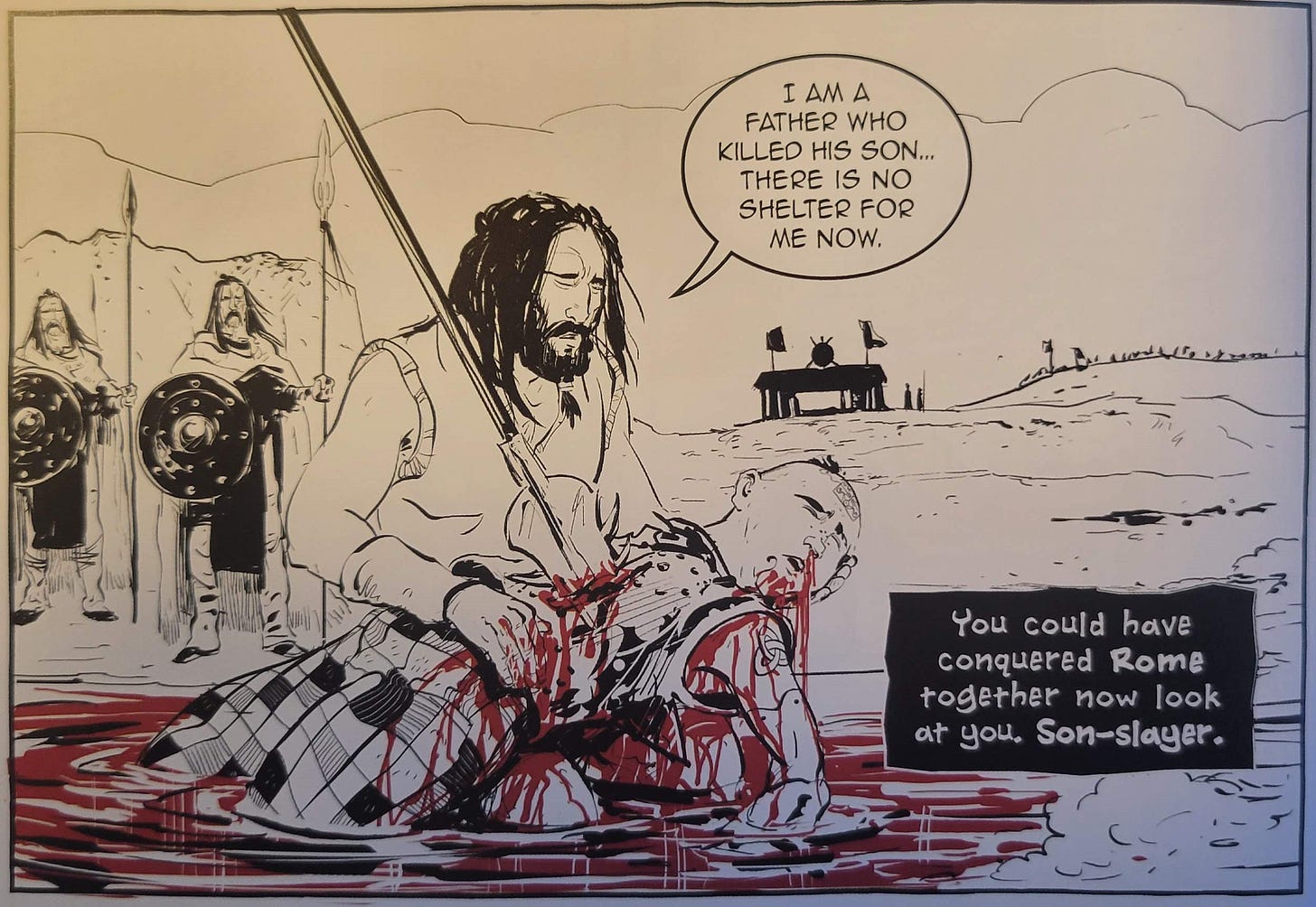

Hound’s exchange between Cú Cullan and Conla only lasts for a single exchange of blows. Conla knocks Cú Cullan to the ground and as he stands he hallucinates a demonic face on Conla, prompting him to cast the gae bolg. Cú Cullan learns Conla’s identity (as being Eva’s son, but never actually his name), then proceeds to lament his kinslaying.

Cú Cullan’s grieving at the end of this chapter in Hound takes cues from William Butler Yeats’ poem “Cuchulain’s Fight with the Sea,” which retells AOA in a very Celtic Twilight format, lacing it with extreme melancholy, natural imagery, and adding references to druids—who are absent from the original text. After killing Conla, Cú Cullan starts going crazy and the demonic overlays from the Morrigan and viewing his allies as monsters. He is only subdued when the druid Kava redirects his anger towards the sea, claiming, “The real demons lie beyond the ninth wave.” He then proceeds to slash at the waves while the Morrigan taunts him in his mind.

Yeats’ poem portrays Cú Chulainn as an older man, which is somewhat in line with how Hound has him in this chapter—by this point he is around 36 in the graphic novel. Following the death of Cú Chulainn’s son in “Fight with the Sea,” Conchobar acknowledges that his nephew’s rage might fall upon Ulster so he sends a druid to cast illusions over him:

“Cuchulain will dwell there and brood

For three days more in dreadful quietude,

And then arise, and raving slay us all.

Chaunt in his ear delusions magical,

That he may fight the horses of the sea.”

The Druids took them to their mystery,

And chaunted for three days.

Cuchulain stirred,

Stared on the horses of the sea, and heard

The cars of battle and his own name cried;

And fought with the invulnerable tide.17

Kava doesn’t cast any specific incantation over Cú Cullan, but the elements of the hero raging in the first place, raising his friends’ concerns, then proceeding to fight the sea are obviously lifted from this Celtic Twilight poem.

In AOA, the mourning of Conla is actually more subdued and shorter than in Hound and “Cuchulain’s Fight.” Cú Chulainn brings a dying Conla around to each of the Ulster champions, whom he embraces, then dies in his father’s arms. Afterwards, the Ulstermen give him a proper burial and observe interesting rites out of respect: “Then his cry of lament was raised, his grave made, and his stone set up, and to the end of three days no calf was let to their cows by the men of Ulster, to commemorate him.”18

While I did enjoy the broad strokes of this chapter in Hound, putting it to more scholarly scrutiny does unveil some of the cracks in the adaptation. Something I’ve lamented a bit is the absence of notable customs and in-depth cultural references in Hound. The total change of “Cú Chulainn’s Boyhood Deeds” would be difficult to echo in the chapter on Conla considering that it is missing some key moments that would foreshadow his relationship to Cú Chulainn (i.e., shooting down the birds and eschewing proper invitation into Ulster). Cú Cullan’s hasty departure from Eva and Skye also leaves a bit to be desired as he only gives Eva the thumb ring without any statement on nurturing their son’s training or behavior. As with the rest of Hound, this chapter continues to dial in on the main character of Cú Cullan and explore his downfall as a hero and descent into madness. In the previous chapter, his fight against Ferdia felt far more emotionally charged while still keeping within the vision of Hound as a tale of tragedy. This chapter is tragic as a whole, but since it is over and done with so quickly it is difficult to find the same emotional weight as the duel with Ferdia. In the context of Irish heroes, AOA is meant to explain why Cú Chulainn has no heirs or legacy outside his own stories, there isn’t much indication in this tale that his kinslaying brings on bad luck or his ultimate downfall. Later collections and variations of Cú Chulainn’s story (Hound included to a degree) use it as an omen for his impending doom. There is likely a case to be made in this story for how unwavering adherence to codes of honor can lead to tragedy, which would have been interesting to explore in this chapter of Hound—as it was somewhat in the previous one—but it is not given as much space as it deserves.

Read the next part here!

Thanks for reading this week’s post! Leave your thoughts below if you’ve read the original story and how well you think it was adapted for Hound!

Refer your friends to Senchas Claideb to receive access to special rewards, including a personalized Gaelic phrase and a free, original short story exclusive to top referees!

Shoot me a message!

Kuno Meyer, “The Death of Conla” in Éiru 1 (1904), 113. https://archive.org/details/riujournalschoo02acadgoog/page/n128/mode/2up?view=theater

Meyer (trans.), “Conla,” §1.

Meyer (trans.), “Conla,” §2. Original Old Irish: “…luingíne chréduma fo suidhe 7 rámada díórda ina láim.”

Meyer (trans.), “Conla,” §2.

Meyer (trans.), “Conla,” §2. Original Old Irish: “Imfuirmed a carpad clis itir a dá láim conátairthed súil.”

Meyer (trans.), “Conla,” §3. Original Old Irish: “‘[M]airg thír i táet in gillae ucut’, ol sé. ‘Matis fir móra na hindsi asa táet donístis, conmeltis ar grian, in tan is mac bec dogní in airbert ucut. Eirged nech ara chend. Nacha telged i tír eter.’”

Meyer (trans.), “Conla,” §4. Original Old Irish: “‘Ním sloindim do óenfiur,’ ol in gillae, ‘& ní imgabaim óenfer.’”

Meyer (trans.), “Conla,” §1. Original Old Irish: “‘…nacham berad óenfer dia chonair & nacha sloinded do óenfiur & ná fémded comlann óenfir.’”

Kuno Meyer (translator,) “The Wooing of Emer,” in Archaeological Review 1 (1888): 254|302. Original Old Irish: “…& ispert co m-bad é a ainm do bretha n-dov Conlui & aspert frie nacha slonnad d'oinfir & nacha m-beurad oinfer dia sligid & na rodobad comlonn ainfir.”

Meyer (trans.), “Conla,” §6-7.

Meyer (trans.), “Conla,” §8. Original Old Irish: “‘Ná téig sís!’ ol sí. ‘Mac duit fil tís. Ná fer fingail immot óenmac, co sechnam, a maic saigthig soailti. Ní soáig ná soairle coméirge frit mac mórgnímach mór ... n-esiut. Artai o ríag cnis fochlóc ót biliu, ba cotat fri Scáithchi scél. Mad Conlae céssad clár clé, comad fortamail taidbecht. Tinta frim! Cluinte mo chlois! Fó mo chosc! Bad Cú Chulainn cloadar! Atgénsa cid ainm asind ón, maso Conlae óenmac Aífe in mac fil tís,’ ol in ben.”

Meyer (trans.), “Conla,” §1.

Whitley Stokes (translator), “The Training of Cú Chulainn” in Revue Celtique 29 (1908): 136|137. Original Old Irish: “‘…& mas mac bheárus tú, oil go maith é, & múin cleasa goile & gaisge dhó, & múin na huile chleasa dhó acht cleas an ghá builg amhain, oir múinfed féin sin dó ar rochtain a nEirinn dó’.”

In AOA, Conla states that is was Scathach who taught him the feats of war (except the gae bolg) §12.

Meyer (trans.), “Conla,” §10.

Meyer (trans.), “Conla,” §11.

Meyer (trans.), “Conla,” §11.

W.B. Yeats, “Cuchulainn’s Fight with the Sea.” https://celt.ucc.ie/published/E890001-004/text001.html

Meyer (trans.), “Conla,” §12.

I have been waiting for this! I am looking forward to more reviews of Celtic media in general and the next installment of your scholarly review of Hound. I appreciate your blog because it is rare to see blogs like this run by scholars.

Your review of this graphic novel has served me as an introduction to the wealth of wonderful literature that has been produced by the Celtic peoples. I admit, although I have a background in literature, my acquaintance and knowledge of Irish literature is scanty at best. Your review has inspired me to delve into what should prove to be a very rich body of literature.