"Hound" - The Scholarly Review III - The Cattle Raid of Cooley, Part 1

The third part of my scholarly review of Paul J. Bolger's dark fantasy graphic novel "Hound"

At last we reach perhaps the most famous story arc from Cú Chulainn’s saga in this adaptation of his life—Táin Bó Cúailnge (“The Cattle Raid of Cooley”). Although the version of events taking place in Hound are heavily truncated from the source material, I decided to split this installment of the scholarly into multiple parts in order to adequately cover the changes made in the graphic novel.

In my first two installments of this review series of Paul J. Bolger’s graphic novel adaptation of Irish legend, I examined the birth, boyhood deeds, martial training, and romantic life of Cú Chulainn. If you have not already read those, you can read them at the links below:

"Hound" The Scholarly Review I - The Conception and Boyhood Deeds of Cú Chulainn

I mentioned in my general review of “Hound” that I might have to split my scholarly review into separate parts. I decided it would be best to do that based on the primary “episodes” that make up the life and saga of Cú Chulainn. This review will be examining Paul J. Bolger’s

"Hound" The Scholarly Review II - The Wooing of Emer and Training of Cú Chulainn

I debated at the end of January whether to post this as my first February post or hold off until this Wednesday (Valentine’s Day). I chose the latter option as it a) gave me more time to research and review the relevant sections of Hound, and 2) since the tales we’re examining in this portion have romantic elements, it fit perfectly …

This review will contain spoilers for Hound, so if you would like to read it before checking out this review, you can get yourself a copy from Darkhorse Comics’ website here!

Unlike my previous two reviews where I did an almost one for one comparison of the events which take place in the source material and adaptation, I will only be focusing on the beats that are adapted in Hound. This is due to TBC being an incredibly dense, sprawling text that Bolger, in some cases, was well within his right to leave out in order to tell a leaner story focused on Cú Cullan.

Background on The Táin and the Irish Custom of Cattle-Raiding

The Táin Bó Cúailnge is one of the closest texts we have to an “Irish Iliad” in the sense of it being an epic tale deeply rooted in the culture, mythology, and warfare of Ireland rounded out by plenty of intrigue and lore to balance out the bloodshed. There are two primary versions (called recensions) of the Táin that are intensively studied. The first recension is contained in a 12th century manuscript called Lebor na hUidre (“The Book of the Dun Cow”) while the second is in the 14th-15th century manuscript The Book of Leinster. The varying details of these recensions range from broad to minute, thus it would take too much time and space to explain them all, but broadly speaking the plot is the same for both of them.

The story of the Táin is centered, as the title suggests, on a cattle raid—the act of one tribe invading the territory of another to take their livestock. The tradition of cattle-raiding was recognized by Gaelic culture in Ireland and Highland Scotland as a legitimate method of acquiring wealth and renown. The warrior-elite of Gaelic clans believed there was more honor to be won in meeting opponents in open combat and taking their material wealth through the means of might than secretly stealing a single sheep. This tradition lasted longer in Scotland than in Ireland, all the way up to the early 18th century before the final Jacobite Rebellion in 1745.

Although the Táin was written in the middle ages, elements of its story may be revealing of what Ireland was like during the Iron Age. Although research into the technology referenced in the Táin has revealed some anachronisms, the Táin is likely one of the closest images we will have for the time being of how Ireland may have been prior to the arrival of Christianity.

One of the most important elements of the Táin’s plot, especially in regards to this review, is that it is where we find the story of Cú Chulainn’s boyhood deeds. His early life is told to Medb and Ailill by Fergus mac Roích and several other warriors who had been exiled from Ulster. From a traditional, modern narrative standpoint, I suppose it makes sense for Bolger to have presented the conception, boyhood deeds, and training first, but I think it makes for an interesting comparison when holding what Cú Chulainn did as a child side-by-side with his duty of defending the entire province of Ulster by himself.

The Táin in Hound

Hound kicks off the Táin segment with a variation of the famous “Pillow Talk” episode featured in the second recension of the text. Following Cú Cullan’s marriage to Emer, Queen Maeve in Connacht is attended to by a mysterious female slave whose black, sketchy speech bubbles and flash of red eyes in a single panel reveals her to be more than she might be letting on. She mentions to Maeve that Alil constantly boasts of his own wealth being greater than his wife’s. Maeve confronts Alil at once and the couple prepare to calculate their wealth in order to settle the quarrel. Meanwhile, the slave girl secretly transforms into Maeve’s Fomorian witch advisor Calatin who oversees the calculation of the goods. She determines Maeve and Alil are matched equally in terms of their personal wealth, but Alil owns one more bull than Maeve. This bull, dubbed “the great Whitehorn”, is a special bull that only has one equal—Connor’s great brown bull in Ulla. Calatin points out that Maeve may ask Connor to loan her the bull for a year and a day so she may have it sire an equally worthy beast, but Maeve intends to keep the bull for herself.

In the original story, it opens on Medb and Ailill1 arguing over their wealth in bed, but without provocation from any other character. They come to a similar conclusion, realizing Ailill owns one more bull than Medb—the white bull Findbennach (“Fair/White-Horned” in Old Irish). At once, Medb wishes to have Findbennach’s equal, the Donn Cúailnge (the “Brown Bull of Cooley”) loaned to her. She sends her messengers to the bull’s owner, Dáire mac Fiachna with an offer of fifty heifers to have the bull loaned to her. She even sweetens the pot by offering Dáire land in Connacht, a new chariot, and Medb’s “own intimate friendship” if he brings her the bull himself.2 Medb’s messengers give Dáire the offer and he accepts at first, but his servant overhears them talking about how Medb would have invaded Ulster to take the bull by force if Dáire refused. When the messengers come to collect the bull, Dáire refuses to give it to them and the messengers return to Connacht to inform Medb of their failure to secure the bull.

In Hound, the Donn Cúailnge (note that it is never actually referred to this or a similar name in the graphic novel) is kept by Emer’s father Ferrell. Calatin and several warriors from Connacht come to Ferrell’s farm to negotiate the terms of the loan. While Ferrell and Emer are entertaining the other guests, Calatin goes to the bull by herself and reveals her true form—the Morrigan—and tells the bull she and it are the “last of [their kind].” The backstory of the Findbennach and Donn Cúailnge is not mentioned in Hound, but this interaction seems to at least hint towards some kind of deeper, supernatural origin. The bulls were original swine herds in service to a king of the Túatha dé dannan3 who got into a fight with each other, shapeshifting into different animals until they both ended up as worms that were swallowed by cows and reborn as the white and brown bulls. Readers who are familiar with the remscél (“pre-story”; i.e., prologue)4 of the bulls’ origin are likely to fully understand it, but for newcomers it’s at least a subtle hint at the deeper lore of the Ulster Cycle and Ireland as a whole.

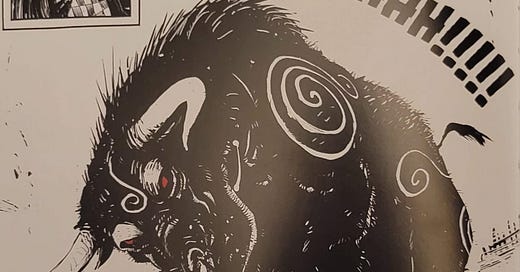

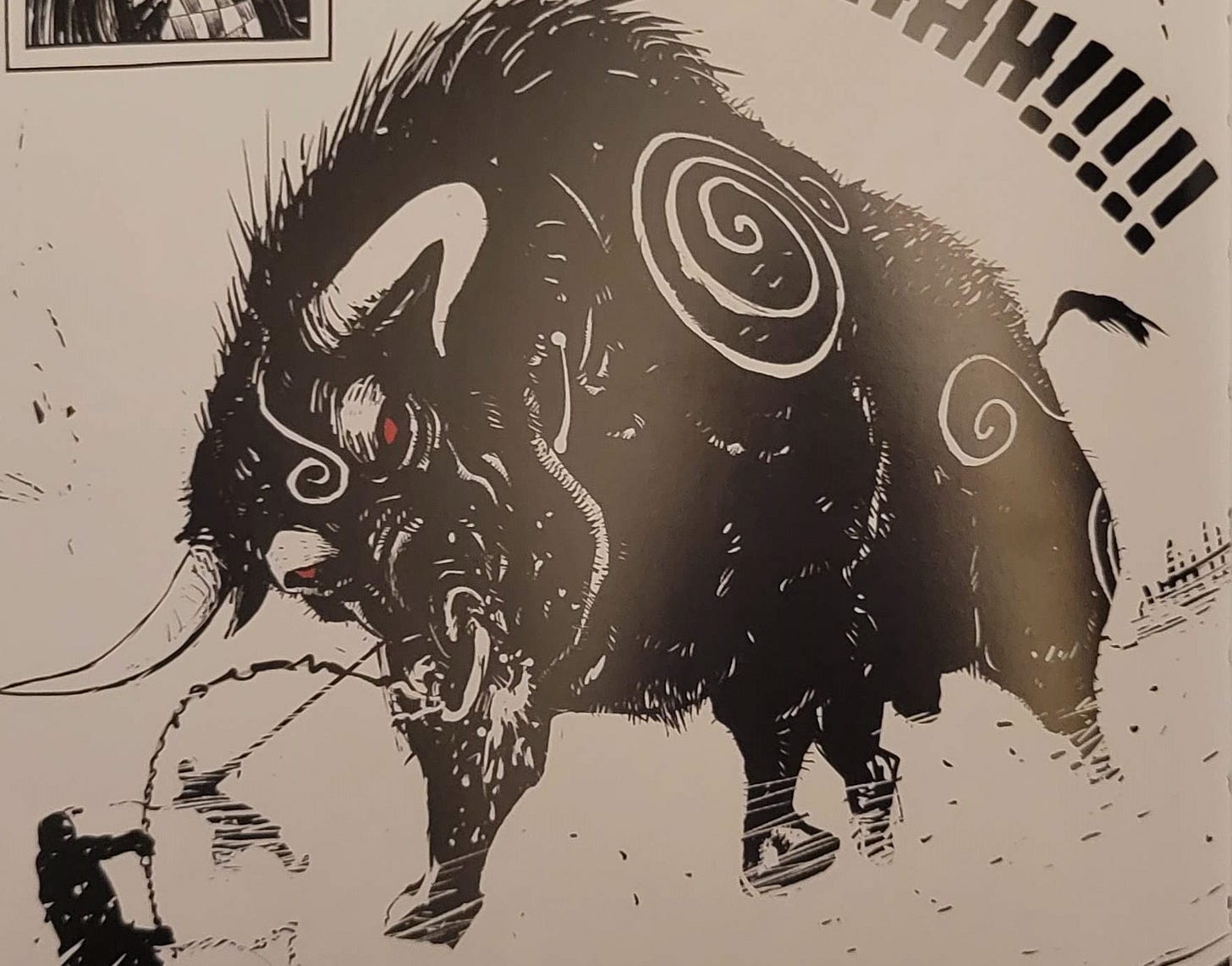

Once night falls, Calatin (the Morrigan) and Maeve’s underlings set the theft of the Donn Cúailnge in motion. Calatin warns Emer about the theft and sends her out to stop the rustlers while her father is being throttled unbeknownst to her. The Donn Cúailnge’s eyes turn red (red eyes in Hound seem to imply the influence of the Morrigan’s bloodlust) as it is being wrangled by the Connachtmen. The bull breaks free and tramples Emer, seemingly killing her just as Cú Cullan realizes something is amiss as he is burning the midnight oil in the fields. He returns to Ferrell’s farm as it’s burning down then pursues Maeve’s lackeys, killing and beheading them. This, rather than the miscommunication in the original text, becomes the catalyst for both Connacht invading to take the Donn Cúailnge by force and Cú Cullan’s primary drive for taking action against Connacht. In the Táin, Cú Chulainn only becomes involved once Connacht begins their invasion, placing a warning for them on a wooden hoop around a pillar stone, then promptly going to have an affair with a woman. This tryst causes Cú Chulainn to completely miss Connacht’s invasion, letting them slip past the borders unchecked. Frustrated at his own failure as a border-guardian, Cú Chulainn rushes to meet the invaders and slay them.

Maeve prepares her army after receiving the heads of her lackeys, promising the warriors of Connacht whatever they wish when they raid Ulla. The Morrigan (still in the guise of Calatin) urges Maeve to prove herself a worthy leader of men; she lops off her hair (making it look like those undercuts that are popular with fans of the History channel show Vikings) and proclaims herself a “warrior queen.” In the original text, the warriors of Connacht and other mercenaries Medb recruits don’t seem to need much reason to join the raid other than the prospect of obtaining wealth and honor for themselves and their tribes. In the next scene, Maeve is shown bathing in a large tub that a horse is sacrificed, mutilated, and dispersed into. It’s a brief scene but obviously a reference to a sovereignty or coronation ritual allegedly practiced (ironically) in Ulster, which Gerald of Wales observed and wrote about in his 12th century text Topographia Hibernica (The Topography of Ireland).5 This scene does not take place in the original Táin and in fact it entirely leaves out the encounter Medb has with Feidelm, the prophetess from the faerie-mounds, who predicts immense bloodshed as a result of the cattle raid and Cú Chulainn being one of the main threats Connacht will have to contend with.6 I suppose having this scene in Hound would be redundant since we already have an inkling of what’s coming to the Connacht invaders, but it would have been interesting to see a psychedelic prophecy scene in Bolger’s style.

Cú Cullan brings the Donn Cúailnge and Emer’s body to Connor’s fort, preparing for her funeral. Connor and Cú Cullan make amends during the burial. Miraculously, Emer awakens much to Cú Cullan’s joy, however, no explanation is given as to how she lived or what methods were taken to heal her. At first, I assumed this might have been one of the Morrigan’s tricks to give Cú Cullan false hope or that this was a hallucination brought on by all the stresses he has had up to this point. However, it seems Emer is entirely alive and well after the incident. There is also an amusing panel where Kava swears to the god Crom upon seeing Emer alive, which I took to be a Conan the Barbarian reference.

In the next scene, Connor, Fergus, and other Ulla noblemen plot their defense against Maeve, putting Cú Cullan at the forefront of their retaliation. Cú Cullan, however, is hesitant to join the fight even after Emer’s close call thanks to the Connachtmen. Connor also calls Maeve’s warriors “muck savages” during this scene, which is a derogatory term the characters of Hound use for the Fir Bolg (a pre-Gaelic people in Ireland), potentially referencing how Connacht became the designated province for their race after they were defeated by the Túatha dé. The Morrigan slips poison into the wine vats that are delivered to Connor and his subordinates. Upon drinking from it, they are all struck down ill. This scene is a great departure from one of the key plot points in the original Táin that is a major reason why Cú Chulainn ends up fighting the entirety of the Connacht army by himself—Noinden Ulad (“the Debility of the Ulstermen”).7 In one of the stories preluding the Táin, the otherworldly woman (potentially a goddess) Macha curses all the men of Ulster after she is forced to run a footrace while she is pregnant with twins. The curse is set to last for nine generations, coming into effect during the province’s greatest times of need, afflicting all the Ulstermen for nine days to suffer pains like that of childbirth the entire time. Women, children, and Cú Chulainn are the only ones exempt from the curse—the reasons for Cú Chulainn not be affected are speculated but may include clauses such as him still being underaged during the events of the Táin (in the original story his is only 17, but in Hound he is around 26 years old), the fact he is partially descended from a god, or that his father Súaldam might not actually be from Ulster. The problem I found with Bolger’s take on the Debility is that the Morrigan only poisons Connor and the other nobles (who aren’t exactly given any characterization), which may be trying to suggest that they are unable to lead their warriors and tenants into battle. With the Debility in the Táin, it is clear that the curse affects the entirety of Ulster’s adult male population, not only the nobles. In Hound, Cú Cullan therefore felt shoehorned into being the sole defender of the province as at any point the other able-bodied warriors could have taken up arms even without leadership of their chieftains.

In Cú Cullan’s first strike against the Connacht invaders, he ambushes a scouting party in the forest during a rainstorm, making for some particularly striking, grimdark scenery. It ends with him beheading all of them and leaving a warning carved into one of their torcs, sticking quite close to the first engagement Cú Chulainn has with the invaders in the original text and the warning he leaves behind.8 In Hound Ferdia seems to assume the role Fergus mac Roích9 did in the original text, serving as the “devil’s advocate” who warns Maeve of the danger Cú Cullan poses and generally acts as a voice of reason amidst the battle-hungry Connachtmen.

Maeve presses her army on, heedless of Ferdia’s warnings, and comes upon a river where the Morrigan is washing a crown that resembles Maeve’s dripping in blood. She warns that all of the Connacht army will perish if they cross the river. The Connachtmen continue their march and are suddenly attacked by Cú Cullan who hurls sling stones at them in a sequence reflective of one strategy Cú Chulainn employs in the original, halting the invaders’ advance by a ford as well. Cú Cullan meets Ferdia face to face and bids him to deliver Maeve a message: “Tell your queen to send a champion against me in the ford of the glen at dawn…Pass on my offer. One fight at day… Or I kill everyone.” In the original Táin, Cú Chulainn makes a similar demand to the Connachtmen when they ask him to stop using his sling, which he has used to kill them by the hundreds for nights on end. Cú Chulainn’s demand for single combat in the Táin may serve two purposes: 1) to give him more of a chance to stem Connacht’s flow into Ulster without the aid of his sling, and 2) potentially as a way to give himself more honor by defeating Connacht’s best warriors one man at a time. For as strong as the sagas’ Cú Chulainn is, he is still smart enough not to take on the entirety of Connacht’s army at once. Hound’s Cú Cullan, however, makes the bold claim that he could fight and kill all of Maeve’s army. While his favor with the Morrigan might provide him with the ferocity to take on such a challenge, even his superhuman feats have limits.

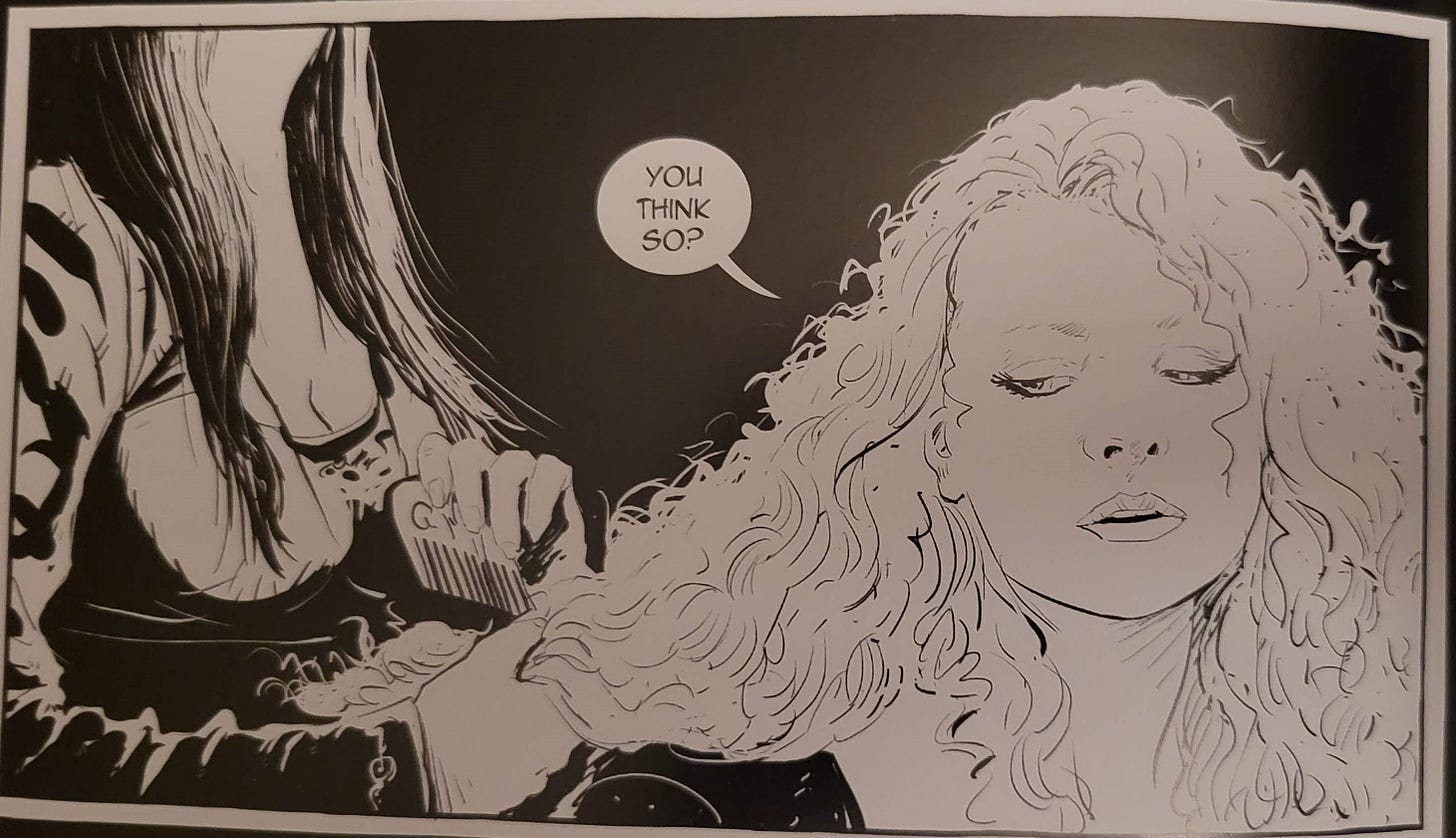

Ferdia relays the message to Maeve and she demands that he prepare to duel Cú Cullan. However, Ferdia is unwilling to fight his friend and acknowledges that he is unbeatable.

Overall Thoughts (and Lore Tidbits)

It may be premature to include the entirety of my thoughts in this segment, but I will use this place to point out a few things that didn’t fit in the main body of the review. This part of Hound, in particular, I felt was chockfull of references and repurposing of different aspects of not only the sagas but other elements of Irish folklore and culture.

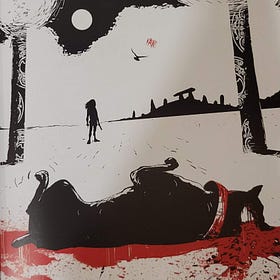

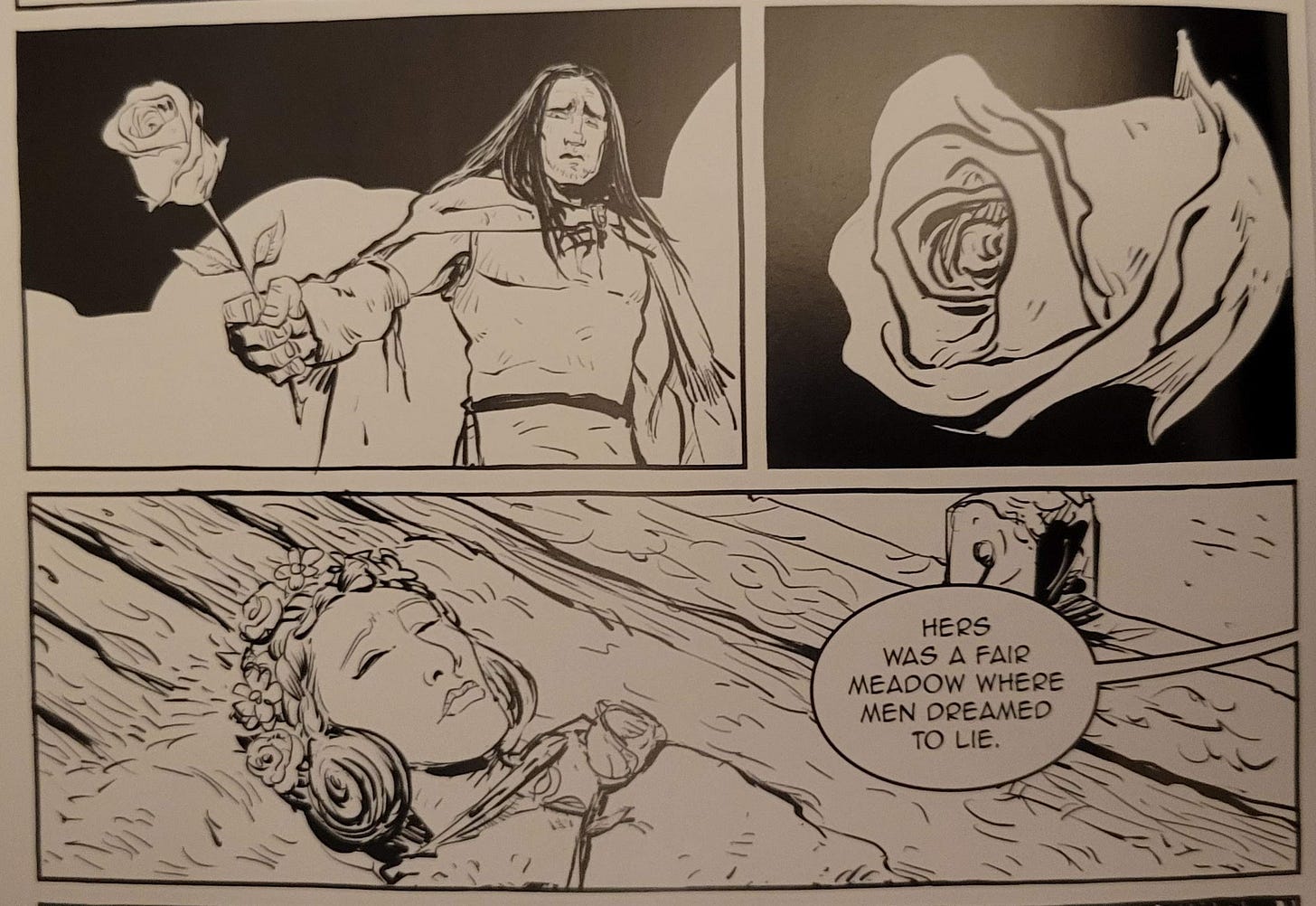

As Cú Cullan lays a rose on Emer’s body, he says, “Hers was a fair meadow where men dreamed to lie” which is likely repurposed from “The Wooing of Emer” when a juvenile Cú Chulainn calls Emer’s breasts a fair plain.

The Morrigan’s washer woman form at the river where she meets Maeve is a clear reference to the various supernatural heralds of death in Gaelic folklore that include the Banshee and the bean-nighe. Both entities are usually seen washing the garments of people who are about to die. It is an interesting repurposing of the Morrigan’s role as a goddess of death, or more so a goddess with prophetic powers. Perhaps this is the closest we might find to a Feidelm-like character in Hound.

In the same scene, the Morrigan says to Maeve, “His river of blood will mark your entry into Tigdun.” An asterisk provides the translation of “Hell” when this is actually a variation of the place name Tech Duinn, “The House of Donn”, which was a potential afterlife located under the sea in Gaelic belief where it was believed all the souls of Gaelic people went after they died. Tech Duinn gets its name from the mythological figure Donn, a son of Mil, whose followers would take Ireland from the Túatha dé and become the Gaelic people.

So far, the Táin segment of Hound doesn’t exactly capture the same scope of this grand invasion that the original saga builds up. I think part of it boils down to how the Debility of the Ulstermen was handled where the Morrigan’s poison seemingly only afflicted the nobles rather than the entire warrior population of Ulster like in the saga. Realistically, any warrior worth his salt at the time who was not affected by the Debility would have been able to gather enough support to fight off at least part of the invasion. I suppose this is one of the cases where it was more helpful for me to put blinders on my scholarly analysis and remember that Bolger is focusing the story primarily on Cú Cullan and his personal journey rather than the machinations of the other characters and institutions in his world. Consequentially, however, this part of the story feels much less epic than the epic it is based upon.

Looking towards the next part of the Táin, we will see how more of the emotionally climatic moments are adapted in Hound, which I am happy to say I am looking forward to covering!

Read the next part here!

Thanks for reading this latest installment of my scholarly analysis of Hound! Have you read the Táin or other versions of it? Share your thoughts about how Hound handled it by hitting the button below!

Refer a friend to Senchas Claideb using the button below and gain access to special rewards, including a personalized Gaelic phrase and a free, original short story!

Follow me on other social media platforms!

Facebook

Instagram

Twitter (X)

Special Announcement! New Story Release!

I am excited to share that DMR Books has released their latest anthology Die By the Sword Volume II! This collection contains twelve tales of sword & sorcery fantasy, including my latest story “Balefire Beneath the Waves” featuring my series characters Eachann MacLeod and Connor Ua Sreng.

In this story, the lads pledge their service to a gruff sailor who has been travelling the world with his daughter, hunting a mysterious sea monster whose existence has haunted him since his youth. Eachann, Connor, and the small crew of the mad sailor’s ship soon find more than they bargained for in the stormy grey seas north of Scotland…

You can pick up your copy of Die By the Sword Volume II in paperback, hardcover, or eBook from DMR Books’ website! Be sure to leave a review and spread the word with friends, family, and fellow fans of S&S!

The names of the characters in Hound are slight anglicizations of their original Irish names, so when I am referring to the source material I will use the original names but any anglicized versions will be referring to the graphic novel.

Táin Bó Cúailnge from the Book of Leinster. Translated by Cecille O’Rahilly, 2014. §83-6. https://celt.ucc.ie/published/T301035/.

Full Translated Text:

‘Go you there, Mac Roth, and ask of Dáire for me a year's loan of Donn Cúailnge. At the year's end he will get the fee for the bull's loan, namely, fifty heifers, and Donn Cúailnge himself returned. And take another offer with you, Mac Roth: if the people of that land and country object to giving that precious possession, Donn Cúailnge, let Dáire himself come with his bull and he shall have the extent of his own lands in the level plain of Mag Aí and a chariot worth thrice seven cumala, and he shall have my own intimate friendship’.

These are the ancient, potentially godly predecessors of the Gaelic people in Ireland. For more information about a few of them, check out this post I made the other week:

The Old Gods of Éirinn

The pre-Christian deities of Ireland are the great subject of speculation and misinterpretation in modern scholarship and popular culture. Given what little evidence Pagan Celts left behind about their gods and their overall religion, it is best to make carefully-informed theories and ideas on the subject but the com…

The most approachable version of the Táin that contains the pre-stories to help contextualize the main narrative is Thomas Kinsella’s The Táin.

The Topography of Ireland by Gerald of Wales. Translated by Thomas Forester, 2000. 77-8. https://www.yorku.ca/inpar/topography_ireland.pdf.

Full Translated Text:

There are some things which shame would prevent my relating, unless the course of my subject required it. For a filthy story seems to reflect a stain on the author, although it may display his skill. But the severity of history does not allow us either to sacrifice truth or affect modesty; and what is shameful in itself may be related by pure lips in decent words. There is, then, in the northern and most remote part of Ulster, namely, at Kenel Cunil, a nation which practises the most barbarous and abominable rite in creating their king. The whole people of that country being gathered in one place, a white mare is led into the midst of them, and he who is to be inaugurated, not as a prince but as a brute, not as a king but as an outlaw, comes before the people on all fours, confessing himself a beast with no less impudence than imprudence. The mare being immediately killed, and cut in pieces and boiled, a bath is prepared for him from the broth. Sitting in this, he eats of the flesh which is brought to him, the people standing round and partaking of it also. He is required to drink of the broth in which he is bathed, not drawing it in any vessel, nor even in his hand, but lapping it with his mouth. These unrighteous rites being duly accomplished, his royal authority and dominion are ratified.

TBC. O’Rahilly (trans). §240-300

Full Translated Text:

[Medb:] ‘I care not for your reasoning, for when the men of Ireland gather in one place, among them will be strife and battle and broils and affrays, in dispute as to who shall lead the van or bring up the rear or first cross ford or river or first kill swine or cow or stag or game. But speak truth to us, Feidelm. O Feidelm Prophetess, how do you see our army?’ ‘I see red on them, I see crimson’.

And Feidelm began to prophesy and foretell Cú Chulainn to the men of Ireland, and she chanted a lay:

[Feidelm:]

I see a fair man who will perform weapon-feats, with many a wound in his fair flesh. The hero's light is on his brow, his forehead is the meeting-place of many virtues.

Seven gems of a hero are in his eyes. His spear heads are unsheathed. He wears a red mantle with clasps.

His face is the fairest. He amazes womenfolk, a young lad of handsome countenance; yet in battle he shows a dragon's form.

Like is his prowess to that of Cú Chulainn of Muirtheimne. I know not who is the Cú Chulainn from Murtheimne, but this I know, that this army will be bloodstained from him.

Four sword lets of wonderful feats he has in each hand. He will manage to ply them on the host. Each weapon has its own special use.

When he carries his ga bulga as well as his sword and spear, this man wrapped in a red mantle sets his foot on every battle-field.

His two spears across the wheel-rim of his battle chariot. High above valour (?) is the distorted one. So he has hitherto appeared to me, but I am sure that he would change his appearance.

He has moved forward to the battle. If he is not warded off, there will be destruction. It is he who seeks you in combat. Cú Chulainn mac Sualtaim.

He will lay low your entire army, and he will slaughter you in dense crowds. Ye shall leave with him all your heads. The prophetess Feidelm conceals it not.

Blood will flow from heroes' bodies. Long will it be remembered. Men's bodies will be hacked, women will lament, through the Hound of the Smith that I see.

A version of the story can be read in full here: https://www.maryjones.us/ctexts/debility.html

TBC. O’Rahilly (trans). §460-510.

Full Translated Text:

Sualtaim went with warnings to the Ulstermen. Cú Chulainn went into the wood and cut a prime oak sapling, whole and entire, with one stroke and, standing on one leg and using but one hand and one eye, he twisted it into a ring and put an ogam inscription on the peg of the ring and put the ring around the narrow part of the standing-stone at Ard Cuillenn. He forced the ring down until it reached the thick part of the stone. After that Cú Chulainn went to his tryst…

The nobles of Ireland came to the pillar stone and began to survey the grazing which the horses had made around the stone and to gaze at the barbaric ring which the royal hero had left around the stone. And Ailill took the ring in his hand and gave it to Fergus and Fergus read out the ogam inscription that was in the peg of the ring and told the men of Ireland what the inscription meant.

And as he began to tell them he made the lay:

[Fergus:]

This is a ring. What is its meaning for us? What is its secret message? And how many put it here? Was it one man oft many?

If ye go past it tonight and do not stay in camp beside it, the Hound who mangles all flesh will come upon you. Shame to you if ye flout it.

If ye go on your way from it, it brings ruin on the host. Find out, O druids, why the ring was made.

It was the swift cutting(?) of a hero. A hero cast it. It is a snare for enemies. One man—the sustainer of lords, a man of battle (?)—cast it there with one hand.

It gave a pledge (?) with the harsh rage of the Smith's Hound from the Cráebrúad. It is a champion's bond, not the bond of a madman. That is the inscription on the ring.

Its object is to cause anxiety to the four provinces of Ireland—and many combats. That is all I know of the reason why the ring was made.

I’ve mentioned in the previous installments of this review that the character of Fergus was greatly diminished from his original role in the sagas. He was one of Cú Chulainn’s foster-fathers and was an established hero in his own right, not simply a side character as he is relegated to in Hound.

You are providing a very well-deserved boost to the reputation of a graphic novel, and, concomitantly, to other graphic novels. They are not just glorified "comic books" as some would characterize them. The research Bolger has done into Irish history and myth--as you point out--deserves scholarly examination--as you have provided. Many other graphic novels deserve a like treatment. Kudos to you and to Bolger.

I appreciate how you treat Hound as an adaptation, I feel like a lot of people treat mythic narratives as a set of facts in a wiki article rather than proper narratives, so the detailed comparisons are nice to see.