"Hound" The Scholarly Review II - The Wooing of Emer and Training of Cú Chulainn

The second part of my scholarly review of Paul J. Bolger's dark fantasy graphic novel "Hound"

I debated at the end of January whether to post this as my first February post or hold off until this Wednesday (Valentine’s Day). I chose the latter option as it a) gave me more time to research and review the relevant sections of Hound, and 2) since the tales we’re examining in this portion have romantic elements, it fit perfectly with the holiday.

In my first part of the scholarly review of Paul J. Bolger’s Hound, I examined the sections of the graphic novel adapted from the episodes of Cú Chulainn’s conception and boyhood deeds. I compared how they were adapted to the original stories from the manuscript texts and added my own thoughts as to what worked and what didn’t in this new interpretation of one of Ireland’s greatest heroes.

If you haven’t already, I highly suggest taking a look at part one to catch up on what’s going on and for context on the graphic novel and the stories it is based upon:

"Hound" The Scholarly Review I - The Conception and Boyhood Deeds of Cú Chulainn

I mentioned in my general review of “Hound” that I might have to split my scholarly review into separate parts. I decided it would be best to do that based on the primary “episodes” that make up the life and saga of Cú Chulainn. This review will be examining Paul J. Bolger’s

Also, if you have not read Hound, there will be major spoilers for it in this review (also spoilers for centuries old stories). So if you would like to experience Hound, spoiler-free, you can purchase it from Dark Horse Comics here.

This next part of Hound is based off two stories about Cú Chulainn’s development as a young man and warrior: Tochmarc Emire (“The Wooing of Emer”) and Foglaim Con Culainn (“The Training of Cú Chulainn”). These tales both cover the martial training Cú Chulainn receives from the warrior-woman Scathach, but differ primarily in that “The Wooing of Emer” has the added plot of Cú Chulainn attempting to woo and marry Emer. For this review, I will be dividing my analysis by first examining how the courtship plot of “The Wooing of Emer” is adapted in Hound, then go on to examined how “The Training” is adapted, which will mention elements from both Foglaim Con Culainn and Tochmarc Emire. First, however, I will give a brief overview of the tales.

The Wooing of Emer

This tale, separate from the “Boyhood Deeds” episode found in Táin Bó Cúailnge (“The Cattle Raid of Cooley”; hereafter referred to as TBC), follows the story of how Cú Chulainn meets and marries his wife Emer. The exact age Cú Chulainn is during this tale is uncertain, as his foster-father Fergus mac Roich in TBC claims Cú Chulainn trained under Scathach when he was six years old and marries Emer when he is seven. My advisor in grad school, however, pointed out that Cú Chulainn might have been much older. This is one of the parts of Irish mythology (or mythology in general) that can be confusing to casual audiences—there is not as clear a timeline as we may think when it comes to stories. Adaptations for general readers may give more clear-cut paths but the truth is that many of these stories come from different resources and traditions even within one culture, thus making it challenging to piece together how storytellers of yore might have told these tales. Whatever the case for his age may be, Cú Chulainn is respected and feared by his fellow Ulstermen, their main concern being that his heroic deeds at such a young age paired with his almost supernatural beauty may cause their wives and other unwed women to fall in love with him. They search for a suitable bride all over Ireland for a year and a day but come back empty-handed. Cú Chulainn himself decides to seek out a maiden he heard of, Emer the daughter of Forgall the Wily. He meets her and her foster-sisters in a playing-field1 outside of Forgall’s fortress and they speak to each other in riddles, in part to test each other’s wit and also to prevent eavesdropping from Emer’s father. After departing back for Emain Macha, Cú Chulainn determines Emer is a worthy bride.

Forgall, however, catches onto Cú Chulainn’s plan and visits Emain Macha disguised as a Scandinavian emissary. He claims Cú Chulainn could increase his martial deeds by training under Domnall the Soldierly and Scathach in Scotland. His hope with this suggestion is to get Cú Chulainn killed by the sheer intensity of the training, Scathach’s especially. Cú Chulainn and several other Ulster champions agree to set out and receive training in Scotland. Before leaving, Cú Chulainn tells Emer of his plan and she reveals that Forgall had orchestrated the plan to send him to Scotland in order for him to die from the training. Cú Chulainn is undeterred, however, and makes a promise with Emer that they will remain chaste until they meet again.

Cú Chulainn and his fellow champions reach Domnall the Soldierly and learn feats of war from him. Feats (called cleasa [pl.]) in Old Irish sagas are types of “special moves” that heroes perform in and outside of combat which demonstrate their prowess as martial artists. Feats as they appear in the sagas are subject to speculation in terms of whether they could actually be performed or not, but for the sake of understanding the gist of what they are, imagine them like powers or techniques characters in Kung-Fu movies or anime shows might use. The feats Domnall teaches Cú Chulainn and the other champions include dancing on a heated flagstone and landing and coiling around spearheads. Domnall teaches everything he can to Cú Chulainn, then directs him to Scathach to learn more in the arts of war.

I will be saving the full description of Cú Chulainn’s training with Scathach but I will note here that one of the major differences between Tochmarc Emire and Foglaim Con Culainn is the role of Aife, Scathach’s sister and rival. Aife and her followers are in conflict against Scathach and her warriors, with Scathach being the aggressor. Not wanting harm to come to her pupil, Scathach gives Cú Chulainn a potion that will make him sleep for a full day, however it proves to be ineffective on him and he joins her in battle. Cú Chulainn fights Aife in single combat but is suddenly disarmed by her and, tricking her into believing her horses and chariot were destroyed, he overpowers her. She offers to fulfil three desires named by him if he spares her, and he lists them as follows: “ ‘[T]hou to give [thyself in] hostage to Scathach, without ever afterwards opposing her, thou to be with me this night before thy dun, and to bear me a son.’ ”2 Cú Chulainn and Aife sleep together, conceiving a son. When Aife shares news of her pregnancy with Cú Chulainn, he gives her a gold thumb-ring that she is to give to their child when he is old enough for the ring to fit on his finger, which Cú Chulainn reckons would be seven years after. He also tells her to name the boy Conla, and places three taboos upon him: “[H]e should not make himself known to anyone, that he should not go out or the way of any man, nor refuse combat to any man.”3

After Cú Chulainn completes his training, he returns to Ireland and approaches Forgall’s fortress. He is denied entry so he vaults over the wall with his “salmon leap” feat and kills half of Forgall’s men, sparing Emer’s brothers. After gathering Emer, one of her foster-sisters, and some of Forgall’s treasure, Cú Chulainn leaps out of the fort and kills the rest of Forgall’s men. Forgall witnesses the entire kidnapping and slaughter, tumbling off his fortress wall and falling to his death. Pursuers chase Cú Chulainn and the maidens in his chariot back to Emain Macha, but he slays them at different points, giving new place-names to areas the combats occur in.

Cú Chulainn and Emer wed but at the wedding feast, the hospitaller and “pot-stirrer” Bricriu brings up the fact Cú Chulainn’s uncle Conchobar, as king of Ulster, has the right of the first night to sleep with Cú Chulainn’s new bride. Conchobar is not one to deny tradition but is also terrified at the prospect of angering his nephew. His druid Cathbad and Fergus mac Roích propose that they lay between Conchobar and Emer to circumvent the right of the first night. Additionally, Conchobar gifts the newlyweds a handsome bridal price and declares Cú Chulainn chieftain of the youths of Ulster.

The Training of Cú Chulainn

Foglaim Con Culainn follows a similar structure as Tochmarc Emire but lacks Emer and the plot of Cú Chulainn courting her entirely, instead giving more attention to the martial traditions and instruction of Cú Chulainn. Instead of travelling to Scotland at the suggestion of Forgall, Cú Chulainn chooses to seek out instruction on his own volition. He and several other champions travel to Scotland and meet Dordmair, the daughter of Domnall the Soldierly. She teaches Cú Chulainn and his allies similar feats as her father in Tochmarc Emire, but her training is so intense that only Cú Chulainn is strong enough to endure the trials. He remains in Scotland to continue his training but meets a stranger from an unknown land who tells him of Scathach, whose school is far to the east in Scythia. Scathach’s house is described as having both male and female students under her tutelage:

[T]hrice fifty girls…with purple mantles and blue. And there were thrice fifty like-aged boys, and thrice fifty great-deeded boys, and thrice fifty champions, hardy and bold, opposite each of those doors, outside and inside, learning valour and feats of knighthood with Scáthach.4

The reference to the girls wearing purple and blue indicates that they are likely of noble status given those were the colors worn by members of the ruling caste in Ireland. There being three distinct categories of boys at different age groups—or rather stages of renown—also indicates that it is primarily an institution for martial training. It is probably the case that fighters of all ages and skill levels have the potential to study the arts of war under Scathach, especially considering Cú Chulainn has already achieved significant mastery over fighting and feats already but desires more instruction. We can also see this in modern martial arts schools (both in Western and Eastern traditions) with consideration for beginners, intermediates, and advanced students. There is also the fact that the upper echelons of students in these schools will sometimes lead their own classes while still receiving instruction from the grandmaster. It may be a similar case with Scathach’s schooling, but rather than slowly climbing the ranks, Cú Chulainn—as we will see—goes directly to the grandmaster herself.

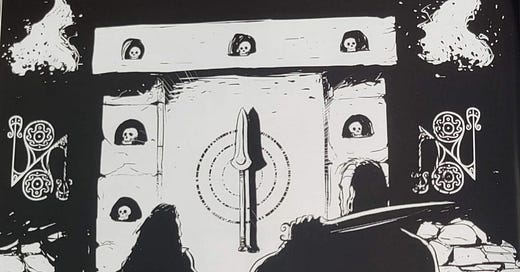

Cú Chulainn travels to the grounds outside of Scathach’s fort and meets youths playing a driving game5 where he has a chance, as in his “Boyhood Deeds” episode, to show off his superior skills in sports. Four Irishmen who also came to learn under Scathach praise Cú Chulainn and show him the entryway to the warrior-woman’s fort—across the bridge of leaps (called the hero’s bridge in Tochmarc Emire). The bridge in both stories is a kind of device that is difficult to balance on and is rigged to fling whoever reaches the end of it back to where he started. It seems a bit like an obstacle one might find in a Wipeout or American Gladiator course and was likely meant to test the athleticism of candidates for Scathach’s training. Cú Chulainn tries and fails three times, being mocked by observers each time. On the fourth time, he uses the feat of the salmon’s leap to clear the bridge entirely and is met by Scathach’s daughter Uathach. Scathach bids Uathach to bring Cú Chulainn to “the house of the barbers.” She does so and the barbers prepare Cú Chulainn for another trial, which involves him standing atop a ridgepole on a house while the barbers throw spears and darts at him. Cú Chulainn cannot let any of the projectiles hit him or draw blood. He is thrown atop the pole and assailed by spears and darts. Rather than simply dodging them, Cú Chulainn goes the extra mile and jumps on each dart, using them like a set of stairs to descend to the ground, inventing an entirely new feat—the dart feat—in the process. The barbers repeat the trial three more times, but Cú Chulainn becomes enraged and kills all of them, placing their heads on spikes before killing another 150 of Scathach’s champions.

Cú Chulainn and Scathach have a highly antagonistic relationship in Foglaim Con Culainn with Cú Chulainn threatening to kill her multiple times despite his desire to learn from her. In their first face-to-face interaction, Cú Chulainn demands that she hands over “‘[T]he mass of jewels and treasures and wealth of the youths of the world, which thou hast (kept) without giving to them.’”6 I interpret this as fosterage fees or perhaps “tuition” fees that boys or their families would have paid to train under Scathach. It was customary that a fosterling was obligated to a portion of the fee once his fosterage ended. Here, Cú Chulainn seems to imply that Scathach has neglected to deliver the rightful share of goods to her former students. Scathach’s sons, Cuar and Catt challenge Cú Chulainn to a duel but their mother forbids the both of them from going; Cuar decides to face Cú Chulainn in single combat. Cuar’s repertoire of feats are included before the fight begins:

[H]is thrice nine feats upon him, as were the apple-feat, thunder-feat, and noise-feat: the wheel-feat, body-feat, hundred-battle-feat, hero's salmon-leap, and cast of sling-stick, and leap over [...], and feat on breaths, and under-blow, and [...] blow, and blow with power, and [...] course finally of parts of spears. So that they were (coming) from him to Cúchulainn like bees actively gathering their heavy collection from the tops of the white flowers.7

Despite his strength, size, and martial inventory, Cuar is slain and beheaded by Cú Chulainn who presents his head to Scathach. Despite having lost one of her sons, she invites Cú Chulainn to sleep inside her house.

During the night, Uathach visits Cú Chulainn and tries to sleep with him but he rebukes her, claiming it a taboo for a woman to lay with a sick man. She puts on a dress and returns but Cú Chulainn, still frustrated, breaks the skin of her hand. Uathach chastises Cú Chulainn for his willingness to hurt a woman, but he still insists on her leaving him alone. Finally, she offers to tell him how he might learn secret feats from Scathach if he lets her sleep with him. He relents and heeds her advice, sneaking behind Scathach the next morning when she goes to commune with the gods and placing his sword against her neck.8 He threatens to kill her but she offers to teach him the secret feats of Catt and Cuar, and the feat of eight waters. Cú Chulainn remains with Scathach for a year, seemingly marrying Uathach as well and potentially acquiring Scathach’s sexual partnership.

Cú Chulainn travels from Scythia to Greece where he meets Aife, who in this tale is daughter of the King of the Greeks. She hosts him for a year, also apparently marrying him. At the end of the year, when Cú Chulainn tries to leave, Aife offers to teach him three “prize feats” if he remains for another year. He accepts and by the end of that year, conceives a child with her. He bids her to raise the boy as a fighter, teaching him every feat except for the gae bolg, then to send the child to Ireland once he has proved himself a worthy warrior.

Cú Chulainn returns to Scathach’s fortress where four warriors from Ireland have been admitted to train under her. Among them is Fer Diad mac Damán. The Irishmen ask to learn every feat Cú Chulainn knows and he agrees to help Scathach train them, but withholds teaching them the gae bolg feat. This training lasts for a year, at the end of which Scathach makes her five students swear an oath of brotherhood and non-violence between each other, but if they should fight then may the best man win.

Before Cú Chulainn and his fellow Irishmen return to Ireland, there is a brief episode involving them going to a Scottish king’s domain that is being terrorized by Fomorians. Cú Chulainn rescues the king’s daughter and kills the leader of the Fomorians, entitling him to a share of the spoils and the princess’ hand. Fer Diad, evidently jealous, rebukes Cú Chulainn, wishing, “‘[M]ay no one on earth ever get renown or fame or lasting distinction on the same road with thee!’”9 Cú Chulainn brushes the curse off and returns to Ulster where he is praised and rewarded with an estate on the border of the province, thus entrusting him as a defender of his homeland.10

Cú Cullan’s Romance and Training in “Hound”

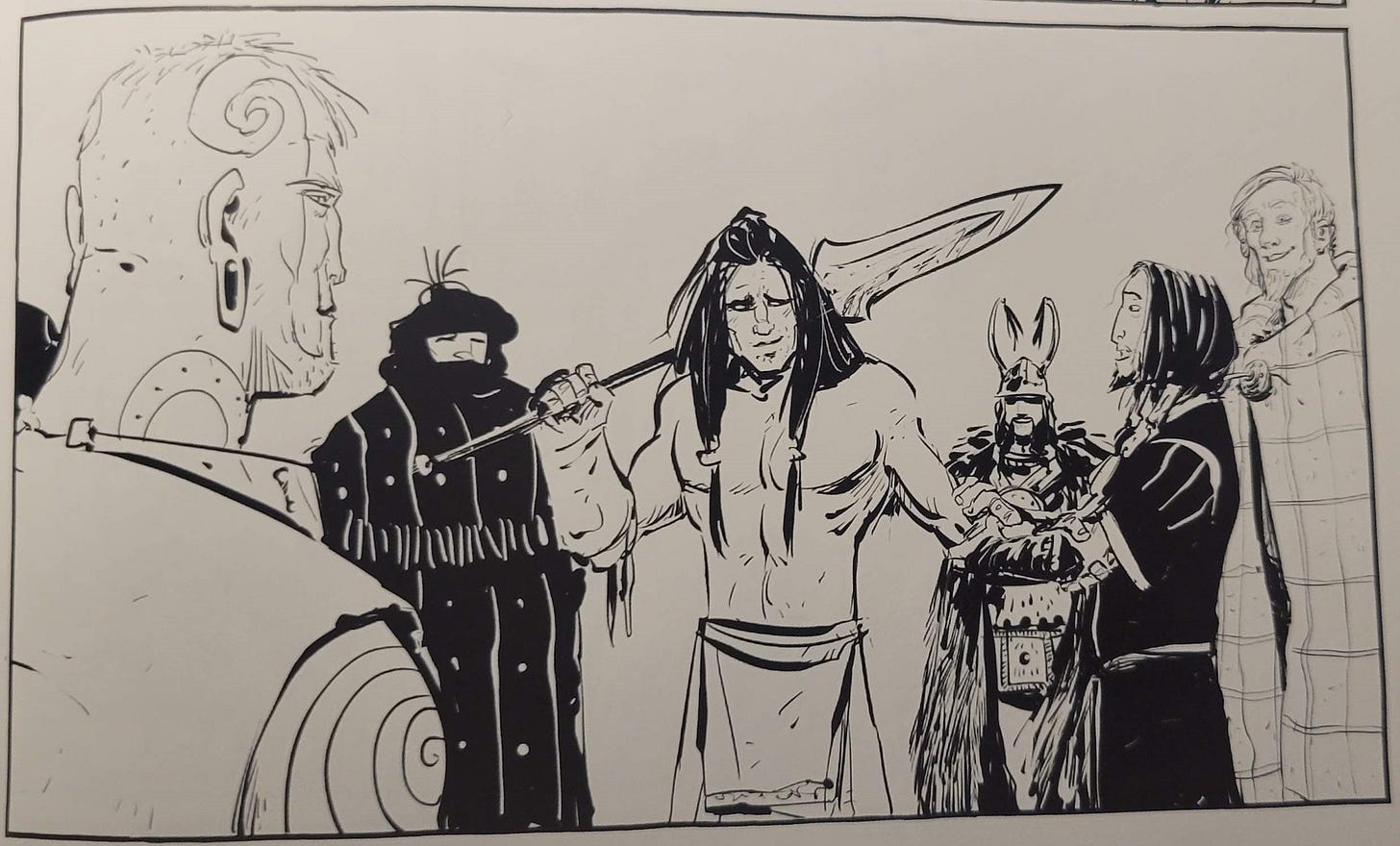

This “chapter” of Hound opens ten years after the “Boyhood Deeds” chapter. King Connor hosts a huge summit in Ulla (Ulster) where tribal rulers from Ireland and further afield congregate in the name of peace. Most notable among them is Queen Maeve from Connacht (and her Fomorian priestess Calatin) who is immediately established as discontent with Connor’s festival and reward of the champion’s portion, a specially-prepared swine gifted to champions at feasts in Medieval Ireland. One of the main events is a ball-and-stick game featuring champions from each tribe, chiefly Cú Cullan playing for Ulla and the Fer Bolg Ferdia playing for Connacht. I must give credit to Bolger here when talking about this game scene as in recent fantasy it seems we don’t get as many scenes like this where characters engage in recreation while also developing the plot and their characters. Considering how important these live sporting events were for ancient cultures (quite literally having similar sorts of excitement and fandom as modern sports), I’m glad that we get to see an adaptation of the athlete side of Cú Chulainn before diving into the bloody deeds in the rest of his saga. Cú Cullan wins obviously but gains the respect of Ferdia.

Following the game, Connor calls for a great, brown bull (the Donn Cúailnge who we will talk about in the Táin installments of the scholarly review) to be sacrificed to the Morrigan. Cú Cullan takes pity on the bull, preaching a nonviolent rhetoric and instead leads a sacrifice of throwing gold and other treasures into a river to placate the war-goddess. Again, Maeve sneers at this display of pacifism, but remarks that Connacht could loot the river in case they ever invade Ulla. Maeve being a naysayer of this ritual and the champion’s portion didn’t exactly sit right with me as though she is one of the antagonists in this story, she just scoffs at traditions that are inherent to her culture. I think this was mostly done to build her up as an antagonist in general, but it just reads more as a person with a somewhat modern, “realistic” philosophy breaking down the traditions of an older culture.

Cú Cullan as well seems to have some anachronistic behaviors during this chapter. He is at first reluctant to enter the match, hanging back in the shadows and moodily saying to Connor, “You know what will happen if I do…Men could die.” At this point, he’s likely aware of the violent impulses that can overtake him during combat or other moments of high stress. The saga Cú Chulainn would never shy away from the opportunity to win at a sporting event or a battle of any kind. We’re likely given this tamer Cú Cullan to make him appear more sympathetic according to nuanced morality—slanting towards good—commonplace in today’s stories. While it is a new angle to look at a mythic figure from, I think it steps a bit out of line from the characteristics of the energetic, wild hero that is Cú Chulainn.

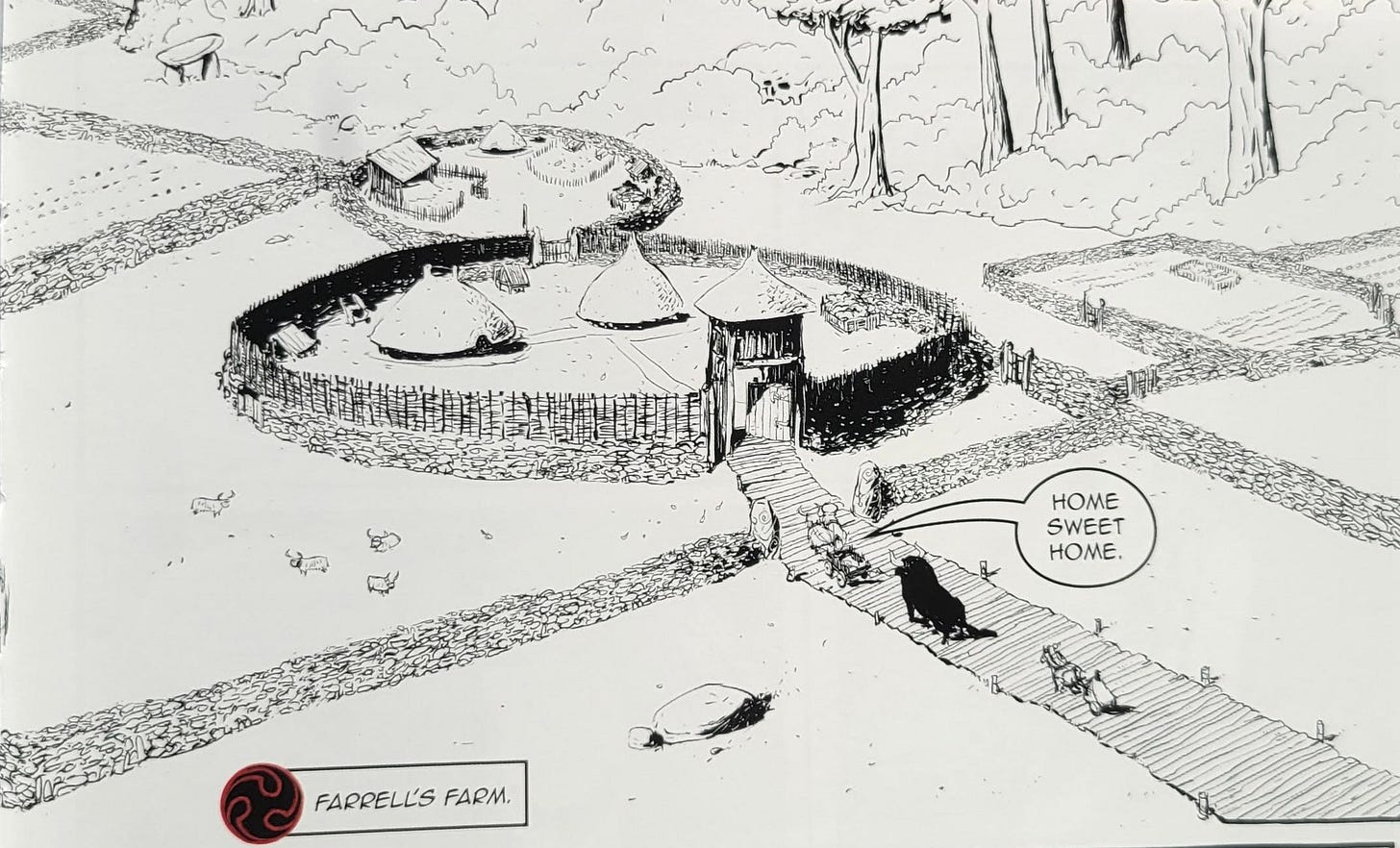

Connor sends Cú Cullan away soon after to the homestead of Farrell, a mild-mannered farmer in Ulla. He calls for his daughter, whom Cú Cullan has been charged with taking back to Connor’s fort, revealing her to be Emer. Hound’s adaptation of Forgall the Wily has almost no recognizable aspects from the original tale (in fact, later in the graphic novel he is just A-Okay with Cú Cullan living with his daughter on his farm) and willingly hands Emer over to Cú Cullan so she can be delivered to Connor and married to him. Farrell also seems to have gone down a few pegs in terms of social status as his home mostly looks like a simple Iron Age farm rather than a tribal leader’s hillfort as is described in Tochmarc Emire. However, given Farrell’s non-antagonistic role in Hound, it does make sense to have his abode be more agrarian than something Cú Cullan would have to slay his way through. We also see that Farrell is the keeper of the Donn Cúailnge.

Emer’s first comment upon seeing Cú Cullan is, “He’s skinnier than I thought he’d be,” which funnily enough is fairly accurate to how saga Cú Chulainn is often described even during the events of “The Cattle Raid of Cooley.” He is, during those stories, still only 17 and lacks a beard, and is mocked for his height and slightness by other warriors. Most modern art portrays Cú Chulainn as a hulking, Conan-like figure, but Bolger deserves much credit for keeping a more restrained physique for his adaptation.

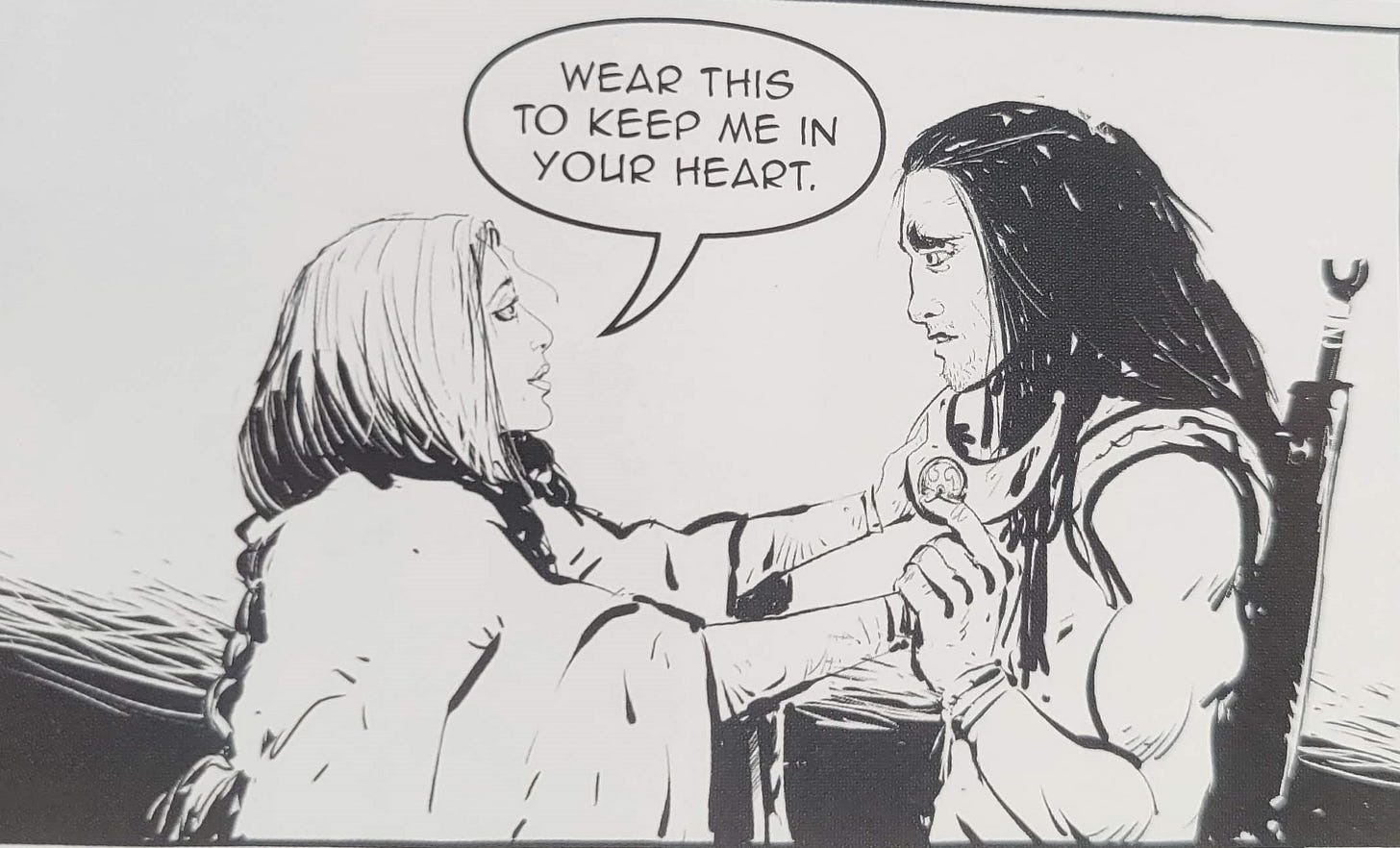

As for Cú Cullan and Emer’s relationship, since Emer is betrothed to Connor, there is not initially the same chemistry and flirting that we see in TE and the riddling is completely absent. Emer expresses her discontent with being betrothed to Connor, whom she claims never to have met. Reading this part, I wondered if Bolger might have incorporated the arranged marriage element from another Ulster Cycle tale about a woman named Deirdre,11 who was betrothed unwillingly to Conchobar. She ends up killing herself to escape the marriage. Emer in Hound, on the other hand, becomes infatuated with Cú Cullan, making advances on him while they are hiding out in a small hut within Connor’s fort. In response to some of Emer’s flirtatious questions, Cú Cullan answers one of them with, “Women don’t like me much,” which is again unfaithful to saga Cú Chulainn who is portrayed as being highly desired by women to the point that the whole plot of TE kicks off because the Ulstermen are worried Cú Chulainn will effortlessly woo their women (see above). Connor catches Cú Cullan and Emer embracing each other and places Cú Cullan under arrest. Before Cú Cullan resists, Fergus12 convinces Connor to send Cú Cullan to the warrior woman Skye (Scathach)13 to “put some manners on him.” Connor agrees, banishing Cú Cullan for three years and calling off his betrothal to Emer. Before Cú Cullan leaves, Emer gives him her necklace so he might not forget her while he is away.

Cú Cullan travels to Alba (Scotland) by first crossing the landmark Hound calls the “Fomorian Stones,” which a handy footnote denotes it as the Giant’s Causeway. While I won’t criticize Bolger for putting a creative spin on this famous Irish landmark, I still can’t help but point out that most stories we have about the Giant’s Causeway are related to another Irish hero, Fionn mac Cumhaill, and there aren’t really any tales that directly associate the Causeway with the Fomorians. Here, the Morrigan tempts him to give into his violent nature but he rebukes her. Later, in Scotland, he is waylaid by a group of kelpies14 who are portrayed in Hound as seaweed-clad Amazonians wielding axes who speak an anglicized form of Gaelic and are led by a woman called Eva (which is the anglicized form of the Irish name Aife), having been orphaned by Roman colonization and warfare. Cú Cullan is saved by a weird guy on stilts who also speaks this anglicized Gaelic, which Cú Cullan (oddly) doesn’t seem to understand. My nitpicky side reared its ugly head again as I realized Bolger likely made the same decision that the writers of Centurion (2010) made—they chose to have the language of the Picts, the aboriginal inhabitants of Scotland prior to the Irish Gaels, be modern Scottish Gaelic. While someone who has never heard a Celtic language before wouldn’t think twice about this, having studied modern Scottish Gaelic for over a decade and Medieval Irish Gaelic for several years, these kinds of details are hard for me to ignore. The reason why I say it’s weird for Cú Cullan, an Irishman, not to understand this clearly Gaelic language is because Scottish Gaelic and Irish came from the exact same language. It is reasonable to assume there would be dialectal differences but for the most part, he would be able to understand Gaelic as it was spoken during his time whether it was spoken in Ireland or Scotland.

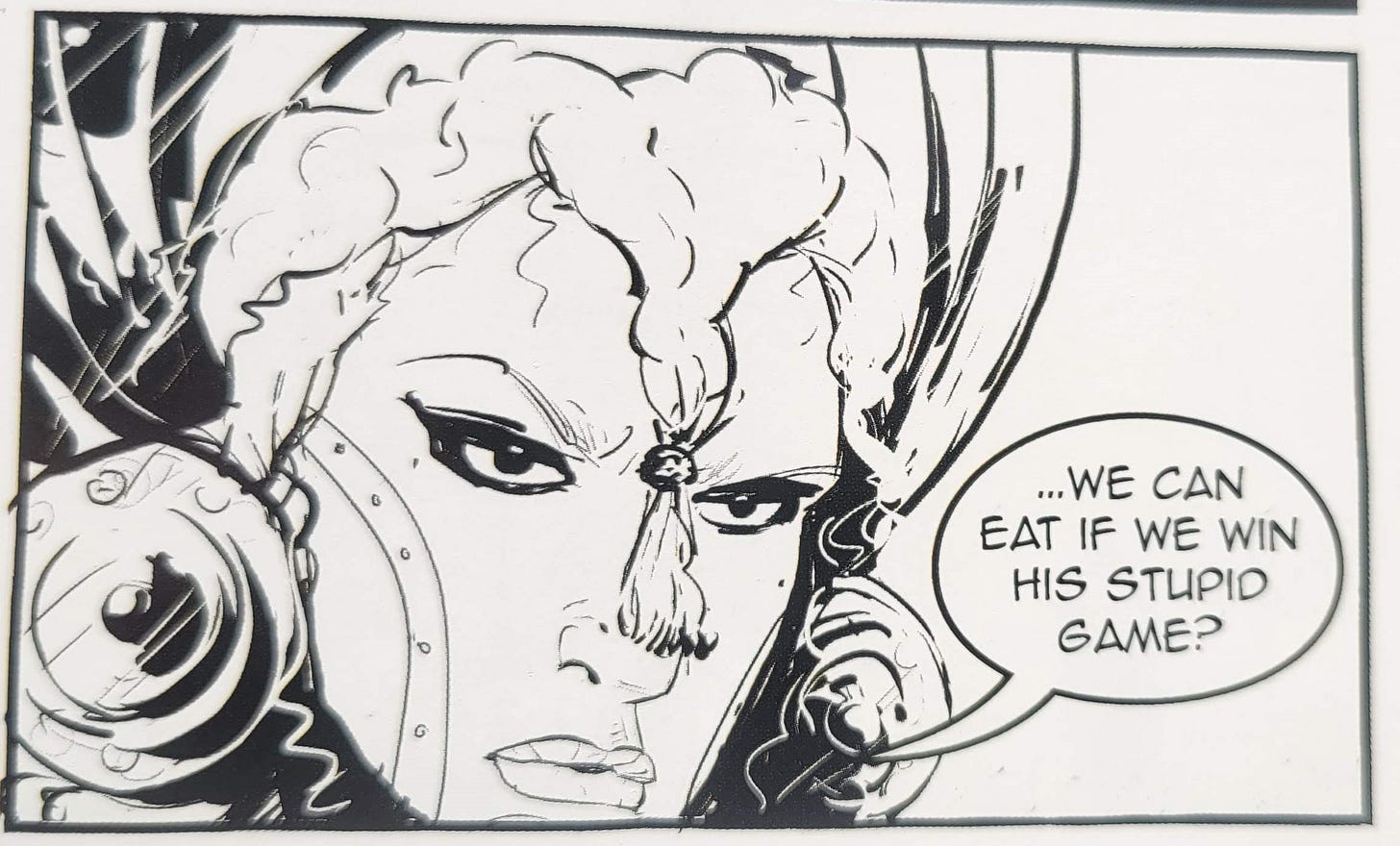

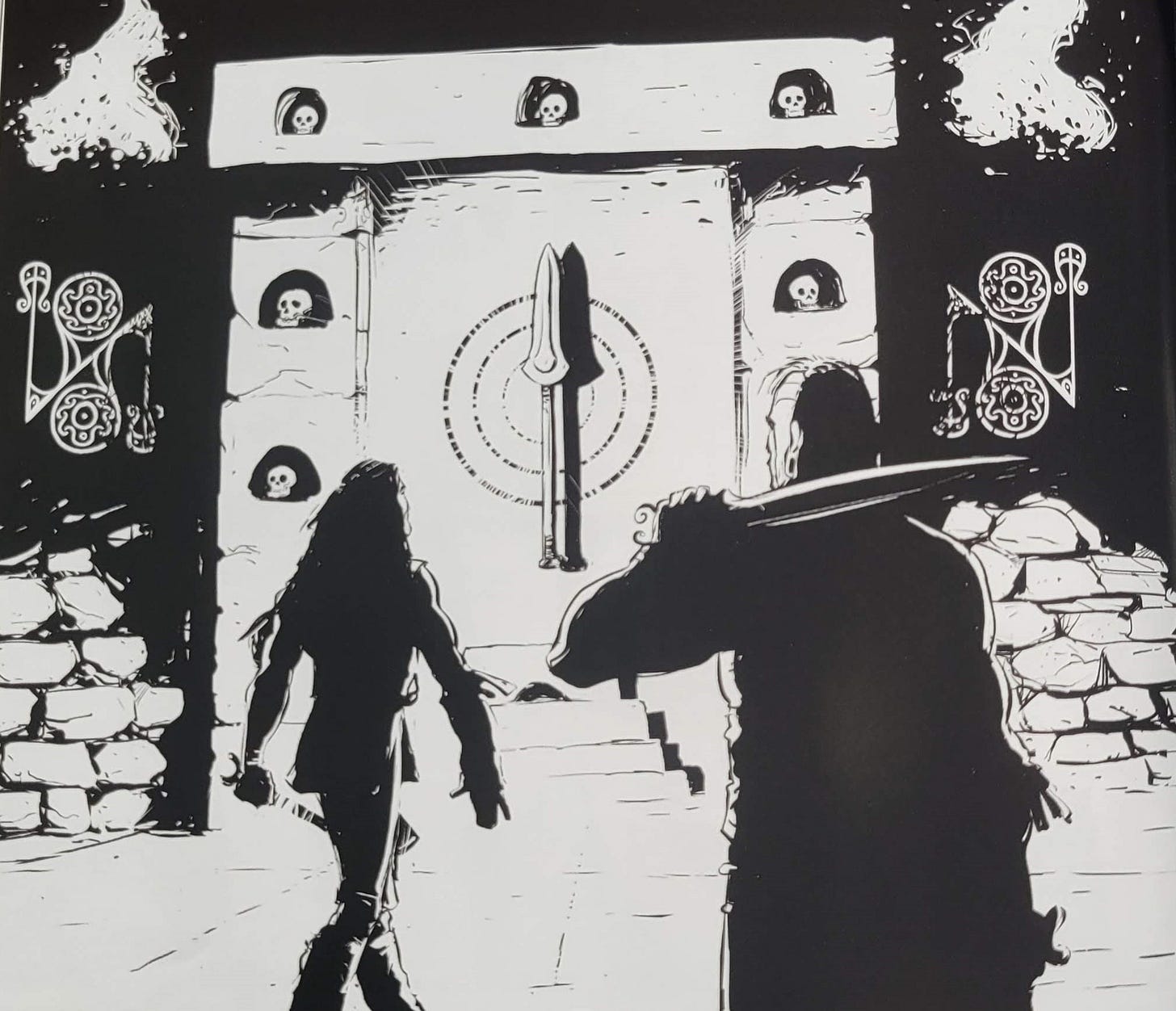

Returning to the story, Cú Cullan reaches an encampment before the hero’s bridge, or bridge of leaps, leading to the Isle of Skye. Here gather warriors from all over the world, including Gaul, Greece, Scythia, and Ireland; Cú Cullan witnesses Ferdia attempt to cross the bridge (called the Shadow Bridge), which is portrayed as a bridge of living stone that flings any who try to cross it back to the start. Ferdia fails his attempt and later talks with Cú Cullan about how he too wound up banished to Skye. He claims that it was “his turn” to sleep with Maeve after the festival in Ulla, but her husband, Prince Alil, confusedly thought it was his and had Ferdia sent away. Interestingly, Ferdia calls Maeve and Alil’s relationship an “open marriage” which is a bit of a simplification from the original saga texts—I will probably expand on this more in the TBC installment of the scholarly review. Ferdia tells Cú Cullan that after he manages to cross the Shadow Bridge, he must place his sword between Skye’s breasts in order to receive her instruction, much like how Uathach in TE informs Cú Chulainn how he can learn from Scathach.

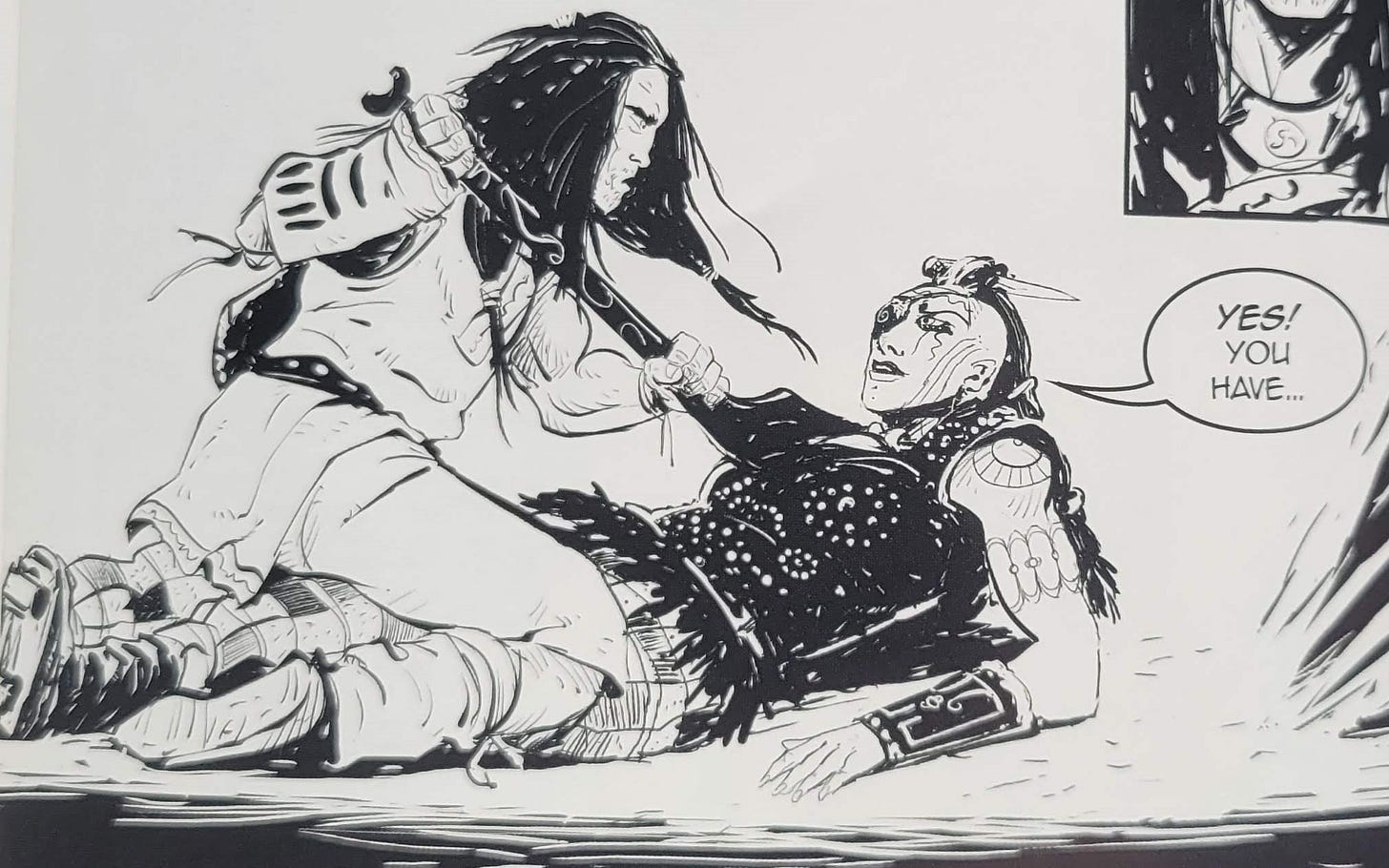

The next morning, Cú Cullan attempts to cross the Shadow Bridge, succeeding on his third try through the use of his Salmon Leap. Landing on the other side, he enters Skye’s school filled with Pictish Amazonians that he deftly avoids to reach Skye in her broch—a tower-like structure built by Picts when they originally inhabited Scotland. Cú Cullan tackles Skye to the ground and places his sword—or weaponized hurly—between her breasts and she agrees to teach him. Meanwhile, Ferdia fails his final attempt to cross the bridge but avoids falling into the whirlpools below thanks to a helping hand from Cú Cullan. Skye dismisses Ferdia but Cú Cullan gives her an ultimatum: if Ferdia leaves then he leaves, thus she misses out on the opportunity to train Ireland’s champion. Cú Cullan also, incredibly, convinces her to let the other warriors cross the Shadow Bridge without any trouble.

In the next scene, Cú Cullan and Ferdia are going through Skye’s armory and mocking the weaker weapons; Cú Cullan bends and breaks swords and spears, which I thought was a nice callback to the Boyhood Deeds episode where he takes up arms and breaks all but Conchobar’s equipment. After a brief sparring match, Cú Cullan and Ferdia notice a spear adorning one wall, which Skye explains is the Gae Bolga (defined by her as “the stretching spear” and “godkiller”).15 Skye claims that it can only be wielded by a child of Lú (erroneously called “the sun god” in Hound), yet this detail is never mentioned in any of Cú Chulainn’s training episodes. We also don’t know anything about the pre-Christian Pictish gods so this weapon, connected with a Gaelic deity, in the hands of Skye—a Pict—feels a bit stretched in terms of logic. The feat of using the gae bolg seems to be one that only Scathach and Cú Chulainn know, the latter ensures that no one else but him learns how to wield the spear potentially so that he may always have the edge if he is ever faced by a fighter who possesses the same skills as him.

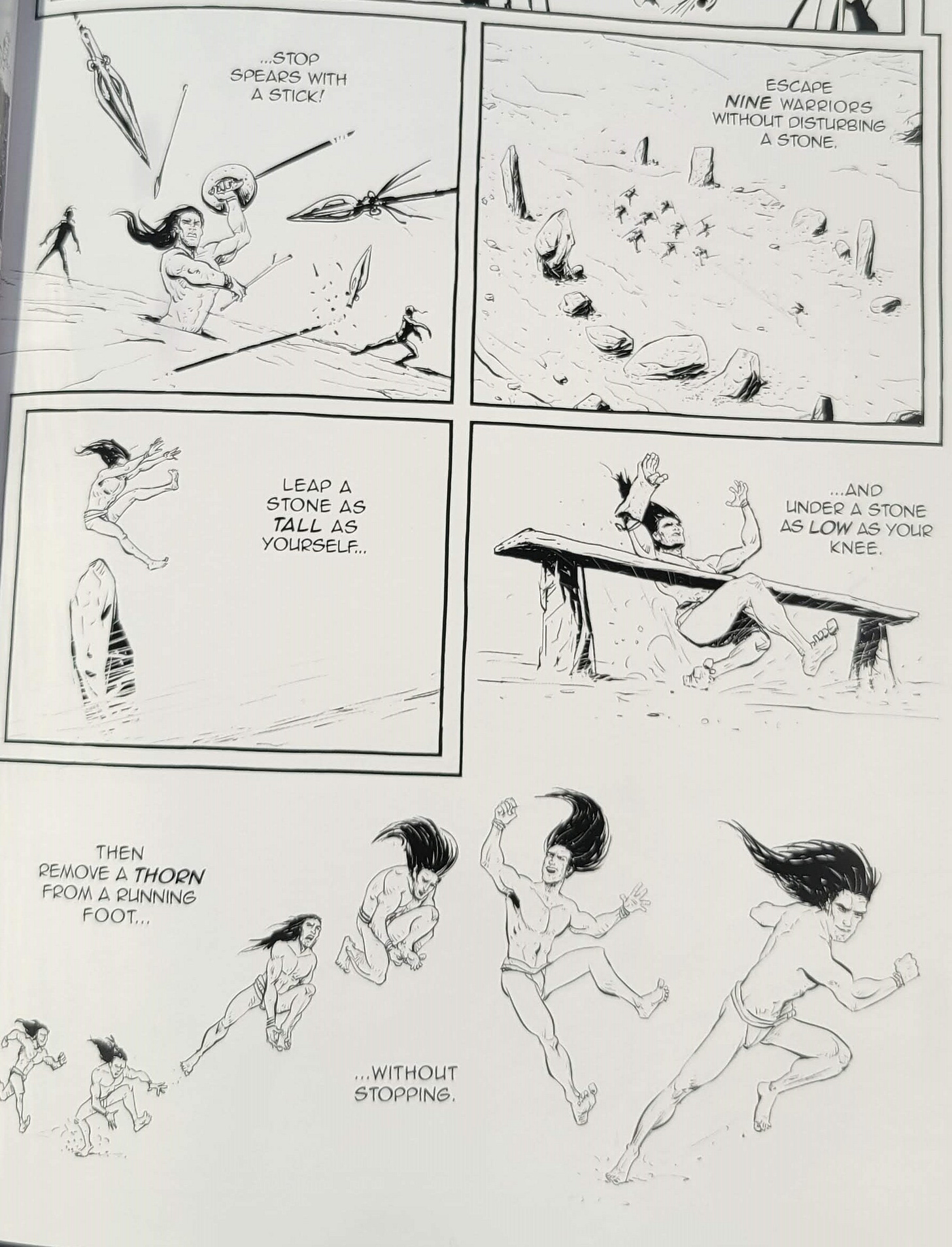

What follows is the “training montage” of Hound where Cú Cullan and his warriors training in different feats, trials, and weapons. It begins with them learning how to cast sling stones and how to “spear-walk” which is a feat Cú Chulainn is said to possess in the sagas. Skye leads them on to “the five tests” which are essentially the rites of passage to gain membership into Fionn mac Cumhaill’s fían warrior group.16 Although it is a clever way of stretching out Cú Cullan’s training with Skye, he never actually undertakes any training like this17 and this fundamentally has different literary meanings compared to the themes of Cú Chulainn’s saga which is mostly concerned with protecting the tribe and ascending to heroic status within society; the Fenian trials on the other hand represent survival skills within the wilderness and the idea of an eternal hunt with the trial involving evasion of pursuers.

Cú Cullan also learns how to wield the Gae Bolga. Aside from Hound’s added clause of the spear needing to be wielded by a child of Lú, the properties of the gae bolg from the sagas are rather straightforward and adapted here rather accurately. Bolger includes the key details that the spear travels on water and must be cast from the foot (although Skye initially throws it at Cú Cullan with an overhand toss). As for the design of Gae Bolga, I felt it looked a bit cartoonish with the overly large blade, making it feel more out of a fantasy than from history or myth. When the barbs on it do come out, the spear looks more in line with the dread, deadly image readers of the sagas might have had of it. However, we don’t have a very detail description of what the mythic gae bolg looks like other than to use other spears as examples.

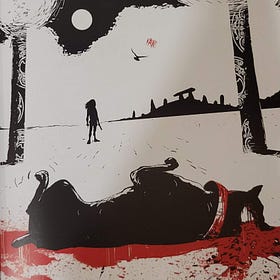

Cú Cullan’s final lesson has him face himself, or as Skye says, “The demon that harvests hate in our mind, screams when blind rage rises…It can destroy us and those we promise to protect.” What follows is a dark, psychedelic journey through Cú Cullan’s mind utilizing images inspired by prehistoric artwork from ancient sites across Celtic-speaking areas. He encounters visions of the Morrigan taunting him, showing him visions of Emer’s corpse being eaten by a crow. Disturbed, he awakens and declares he must return to Ireland.

As Cú Cullan prepares to take his leave, he and Ferdia make a pact of non-violence between each other, sealing it with a blood oath. Suddenly, the school is attacked by Eva and her Kelpies, the reason for why she decides to attack now in particular is unclear other than she simply wants her mother, Skye, slain and to take the school for herself. Eva and Skye fight each other but before Skye can land the killing blow on her daughter, Cú Cullan holds Gae Bolga against her throat, calling for a ceasefire. This coerces Skye into relenting, sparing Eva and repairing their relationship. The conflict between Scathach and Aife in the sagas is not entirely explained, but the text implies that Scathach is the aggressor rather than Aife. The choice to make the adaptation of Aife into Scathach’s daughter seems to kill two birds with one stone as Cú Chulainn sleeps with both Scathach’s sister and daughter in TE. Cú Cullan in Hound does pursue a relationship with Eva despite his devotion to Emer, remaining on the Isle of Skye for four months, at the end of which Eva reveals she is pregnant with Cú Cullan’s son. He gives her a ring meant for the child to wear so he might recognize the boy should their paths ever cross—this is the beginning of another tale we’ll examine later in the the scholarly review. Cú Cullan and Ferdia soon depart Scotland, reaching the Fomorian Stones before going their separate ways. They affirm their pact once more before their separation.

Cú Cullan then reunites with Emer and they are married by the druid Kava. During the entirety of Cú Cullan’s exile, Connor seems to have just fallen into a deep depression over having been cuckolded out of marrying Emer. When we see him again following Cú Cullan’s return, he is disheveled and sleeping alone in his room. He scoffs at the news of Cú Cullan’s return and marriage before returning to sleep.

For the time being, Cú Cullan begins a quiet life with Emer on her father’s farm with hopes for a prosperous, happy future.

My overall thoughts on this chapter

As with Cú Chulainn’s Boyhood Deeds, going into Hound I was curious as to how Bolger was going to handle Cú Chulainn’s specialized training, given how little we know about the feats. Additionally, the romantic plot between Cú Cullan and Emer in this chapter feels much less like the rollicking adventure I always read Tochmarc Emire to be and in some cases more grounded, but in others—particularly Connor’s breakdown—a bit too melodramatic. It doesn’t have the same sense of “fun” that usually surrounds Cú Chulainn’s youthful deeds—despite them also having their fair share of violence and tragedy—which I suppose should be expected for a darker retelling of these tales. I did get more of that sense during scenes Cú Cullan had with Ferdia, and in that case, Bolger made the right choice to show the young warriors’ relationship in this adaptation as we do not get to see as much of it during the training episodes of the sagas. While the stories about Cú Chulainn are mostly centered on him, this part of Hound is really where I began to notice how much the plot and other characters are focused on furthering his story. Originally, the sagas had a lot of other things going on in the background and the other characters felt much more realized and integral to the events; Cú Chulainn, despite being the chief hero of the stories, never felt like everything was happening because of his mere existence. Skye makes special exceptions for Cú Cullan’s friends although they did not complete the Shadow Bridge successfully; having Ferdia fail it slightly diminishes his character as he is supposed to be Cú Chulainn’s equal in strength and skill save that he does not know how to use the gae bolg. I did like how Bolger kept the contentious relationship between him and Skye, however, as there seems to be some kind of conflict that is worth more investigation in the original tales.

I think one of the more jarring parts was Connor’s absolute meltdown over catching Cú Cullan and Emer together as it felt contrived, most likely to get Cú Cullan to Skye since Farrell has a much friendlier role in this adaptation. Even though Forgill’s plan was to get Cú Chulainn killed by sending him to Scathach, Cú Chulainn still chose to go even when told the truth as he wanted to acquire more martial knowledge and strength. Hound’s Cú Cullan is far more passive and pacifist despite his superheroic strength and skill, less willing to do things his saga counterpart would not hesitate to pursue. This in turn switches the power dynamic between him and other characters, particularly Connor. Conchobar in the sagas fears his nephew for his inhuman strength and wildness, but Connor in Hound is able to exploit Cú Cullan’s loyalty and aversion to violence to send him into exile.

The overall relationship Cú Cullan has with Emer, as I mentioned above, doesn’t have the same social complexities and nuances that we find in the original story. The development of their romance is quick, and the consequences of them simply being caught in each other’s arms happen rather abruptly. I believe this is one of the areas of the story that could have benefitted from being more faithful to the original tale. I would have liked to have seen Cú Cullan having to rescue Emer from her father’s fort and cutting down each of her guards while he Salmon Leaps over the walls. I suppose, however, the events of this chapter serve more to further this particular adaptation of Cú Chulainn and the overall themes of Hound.

Read the next part here!

Thanks for reading this installment of my scholarly review for Hound. Next time we will be looking at Hound’s adaptations of probably the most famous Cú Chulainn story—or Irish saga period—the Táin Bó Cúailnge (or “Cattle Raid of Cooley”). That one will likely be very long as well and might even need to be divvied up into smaller sub-parts.

For now, hit the share button below to spread the lore of this review with fans of Irish mythology, comics, or blood-soaked love stories.

Also, refer a friend to Senchas Claideb to receive special rewards including a personalized Gaelic phrase and a free, original short story!

Follow me on other platforms:

Facebook

Instagram

Twitter (X)

And a Special Announcement…

DMR Books has just released the cover page and table of contents for their upcoming anthology, Die By the Sword Volume II! I will be appearing alongside eleven new and returning authors who will bring a total of “…twelve sensational tales, ready to swallow you whole into a world of sword-wielding heroes, exotic locales, strange creatures, and malefic magic spells!”

My story, “Balefire Beneath the Waves”, is another Eachann and Connor story, making this the third of their tales DMR has published in their anthologies, links to which can be found on my publications page.

Die By the Sword Volume II is set to release in early March 2024, so be sure to follow DMR Books to get notified upon release!

In my previous installment of the scholarly review, I talked a lot about fosterage for boys in medieval Ireland. It was likely girls would also have their own sections for play and practicing their arts on playing-fields of households where they were fostered.

“The Wooing of Emer.” Translated by Kuno Meyer, 301. https://celt.ucc.ie/published/T301021/.

“The Wooing.” Meyer (trans.), 302. https://celt.ucc.ie/published/T301021/.

“The Training of Cú Chulainn.” Translated by Whitely Stokes, 119. https://celt.ucc.ie/published/T301038/. Original Irish: trí chaogad ingen ann gach iomdhai díobh sin go mbrataibh corcra & gorma, & do bhadur trí caogad macáoimh iomhaoíse5, tri chaogad macaomh morghlonnach, & trí caogad curadh crúaidhchalma fa chomhair gach doruis díobh, amach & asteach, ag foghluim gaisge & cleasa riderachta ag Sgáthaigh.

As I explain in my previous review, many translations of Old Irish texts use the words “hurly” or “hurling” to describe ball-and-stick games. In actuality, the word “hurling” is not attested until after the Anglo-Norman occupation of Ireland in the 13th century A.D. The sports may have been somewhat similar but usually I will use the verb “driving” to denote these types of games mentioned in saga literature.

“The Training.” Stokes (trans.), 127. Original Irish: “‘An mhét do sétuibh & do mhaoínibh & d'ionnmhus macraidhe an domain atá agadsa gan tabairt dóibh atáimsi d'iarraidh ort anois.’”

“The Training.” Stokes (trans.), 129. Original Irish: “…náoi gcleasa air, mur do bhí ubhall-chleas, torainncleas & fuamchleas, roithchleas, corpcleas, cét- chaithchleas, & iach n-earradh & coir ndealann & leím tar neimh & cleas fur anala & foibhéim ocus fáithbheím & beim go gcomus fáithréim andíaidh do reannaibh slegh, go mbídis sin úaidh chuige amhail beacha ag tionól a ttromchnuasaigh go treabhruighthe do bharraibh na mbánsgoth.”

It is clear that Cuar’s “nine feats upon him” are likely feats that he developed and used himself. Fighters today who practice historical combat, once they gain total mastery over the basics of their art, are able to play with the rules or even break the foundations if they find ways to use them to their advantage.

In Tochmarc Emire, Uathach has a similar tryst with Cú Chulainn and also tells him the secret of how to learn additional feats from Scathach, which differs slightly from Foglaim Con Culainn:

On the third day the maiden advised Cuchulaind, that if it was to achieve valour that he had come, he should go through the hero's salmon-leap at Scathach, where she was teaching her two sons, Cuar and Cett, in the great yew tree, when she was there; that he should then set his sword between her two breasts until she gave him his three wishes, viz., to teach him without neglect, and that he might wed her (Uathach) without the payment of the wedding gift, and to tell him what would befall him; for she was a prophetess.

—from “The Wooing of Emer.” Translated by Kuno Meyer, 300. https://celt.ucc.ie/published/T301021/.

“The Training.” Stokes (trans.), 147. Original Irish: “…‘ní bfuighe duine ar bioth bladh nó nós na buánoirdercus ar choimhslighe riot go bráth’.”

Border guardianship in ancient and medieval Ireland was a very important function for martial heroes given how disparate and territorial tribal lands were at the time. Emmet Taylor, a fellow St. Francis Xavier Celtic Studies grad, explains the function of border guardians in their thesis on Cú Chulainn’s foster-brother Conall Cernach which can be read here.

A more authoritative translation of the Dierdre text still seems to be in the works but for now this version will suffice: https://bardmythologies.com/deirdre-of-the-sorrows/

I discuss the diminishing of Fergus mac Roich’s role in Hound in my first installment of the scholarly review. In short, the original version of him in the sagas is supposed to have more of an emotional, fatherly relationship with Cú Chulainn, but at this point in Hound he is just a simple advisor to Connor.

The characters also deliberately call the location Cú Cullan is to be sent to the Isle of Skye, which people from Scotland or who have been to Scotland will likely know very well as being part of the Inner Hebrides off the west coast. While there is popular belief that this is where Cú Chulainn trained during the sagas, neither the training episodes in TE nor FCC are said to take place on the Isle of Skye. In fact, TE clearly states that Cú Chulainn goes to eastern Scotland to meet Scathach. There might also be the possibility that Scathach is the namesake of the Isle of Skye as the modern Gaelic word for it (An Eilean Sgitheanach) could have some slight similarities but as I am not an etymologist I cannot confidently comment on this.

Kelpies in traditional Gaelic folklore are usually horse-like creatures that will drag anyone foolish enough to ride them into the nearest body of water where they will drown, unable to dismount due to a glue-like substance on the beasts’ backs.

Cú Chulainn’s famous spear is subject to speculation and is explored further in the article “Cú Chulainn’s ‘gae bolga’—from harpoon to stingray spear?” by Edward Petit: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24778337.

From “The Enumeration of Finn’s People,” translated by Standish O’Grady, 92-3 & 100:

No man was taken till in the ground a large hole had been made (such as to reach the fold of his belt) and he put into it with his shield and a forearm's length of a hazel stick. Then must nine warriors, having nine spears, with a ten furrows' width betwixt them and him, assail him and in concert let fly at him. If past that guard of his he were hurt then, he was not received into Fianship.

Not a man of them was taken till his hair had been interwoven into braids on him and he started at a run through Ireland's woods; while they, seeking to wound him, followed in his wake, there having been between him and them but one forest bough by way of interval at first. Should he be overtaken, he was wounded and not received into the Fianna after. If his weapons had quivered in his hand, he was not taken. Should a branch in the wood have disturbed anything of his hair out of its braiding, neither was he taken. If he had cracked a dry stick under his foot [as he ran] he was not accepted. Unless that [at his full speed] he had both jumped a stick level with his brow, and stooped to pass under one even with his knee, he was not taken. Also, unless without slackening his pace he could with his nail extract a thorn from his foot, he was not taken into Fianship: but if he performed all this he was of Finn's people.

Original Irish:

Ní gabtha fer díb fós co nderntái latharlog mór co roiched fillidh a uathróigi. Ocus no chuirthe ann é ocus a sciath les ocus fad láime do chronn chuill. Ocus nónbar laech iar sin chuigi co nái sleguib leo ocus deich nimuiri atturru co ndibruigidís i n-óinfecht é. Ocus dá ngontai thairis sin é ní gabtai a bfianoigecht.

Ní gabtái fós fer díb so co nderntai fuiltfighi fair ocus go cuirthi trí feduib Erenn ina rith é co tigdísim uili ina diaid ar eiccill a gona. Ocus ní bídh aturro acht in craeb do ega. Dá rugta fair do gontai é ocus ní gabthai iar sin. Da crithnaidhidís a airm ina láimh ní gabtai. Dá tucad craeb isin choill ní dá fholt as a fhige ní mó no ghabtai. Dá minaigedh crand crín fá a chois ní gabtái. mina lingedh tar crann bud comard re aédan ocus mina cromad fó cradd bud comardrena glún ní gabtai é. ocus mina tucad in dealg as a chois dá ingin gan toirmesca retha uime ní gabtai a bfianaigecht é. Ocus dá ndernadh sin uili fa do muir Finn é.

However, the case has been made that the test where an initiate must stand in a hole does have parallels with the Boyhood Deeds episode where Cú Chulainn enters the boytroop’s playing field and is waylaid by their driving sticks and balls, which he manages to fend off.

A fascinating and well-researched read! I didn’t realize how complex Cu Cuchlainn’s mythology actually was until now. It’s made me curious about looking more into Celtic mythology, it’s kind of a shame that it’s not given the attention it deserves.

I have been waiting for more of your scholarly review of Hound! I predict that Part 3: The Cattle Raid of Cooley and Part 4: The Deaths of Aífe's Only Son and Cú Chulainn will follow. You compared Cú Cullan and Emer's romance in Hound to the legend of Deirdre but I think it's also similar to the legend of Tristan and Iseult.

If you are interested, here is a list of comics based on Irish mythology that are available as far as I know. I hope it helps!

* About a Bull by M. K. Reed, Caroline Kelsey, Hilary Florido Matt Wiegle, and Farel Dalrymple

* The Cattle Raid of Cooley by Patrick Brown

* Celtic Warrior: The Legend of Cú Chulainn by Will Sliney

* Deirdre agus Mic Uisnigh by Colmán Ó Raghallaigh, Barry Reynolds, and Audrey O'Brien

* Ness by Patrick Brown

* An Táin by Colmán Ó Raghallaigh and The Cartoon Saloon (Barry Reynolds, Adrien Merigeau, Roxanne Burchartz, Ross Murray)

* An Tóraíocht by Colmán Ó Raghallaigh, Paul Young, Michael McGrath, and Diane O'Reilly