"Hound" The Scholarly Review I - The Conception and Boyhood Deeds of Cú Chulainn

The first part of my scholarly review of Paul J. Bolger's dark fantasy graphic novel "Hound"

I mentioned in my general review of “Hound” that I might have to split my scholarly review into separate parts. I decided it would be best to do that based on the primary “episodes” that make up the life and saga of Cú Chulainn. This review will be examining Paul J. Bolger’s Hound as an adaptation of medieval sagas that have been—and are still being—carefully studied and interpreted by Celtic scholars.

In this section, I will be comparing the first part of Hound to the medieval Irish tales Compert Con Culainn (“The Conception of Cú Chulainn”) and Macgnímrada Con Culainn (“The Boyhood Deeds of Cú Chulainn”), covering the early life of the hero Cú Chulainn in the Irish sagas as compared to the adaptation of them in the graphic novel.

Before I launch into the actual review, I wanted to take a moment to explain my “credentials” in the field of Celtic Studies. I hold a Master’s Degree in Celtic Studies from St. Francis Xavier University. My thesis (which can be read here) examined the martial training of boys and young men in Early Medieval Ireland and 17th-18th century Highland Scotland. My research drew largely from the stories of Cú Chulainn from the Táin Bó Cúailnge (“The Cattle Raid of Cooley”; hereafter referred to as TBC) and legal tracts describing the traditional training and education of boys in their early years. Even with other mythologies, my favorite parts of hero stories are their origin tales, as I’m interested in knowing what shaped them into the supermen that they are most famously known to be. I have also been independently studying Celtic myth, history, and language for over a decade. My focus remains on hero-tales and martial traditions in history, mythology, and folklore but I am also interested in other sections within the broader field of Celtic Studies, which includes popular culture.

I must also give some context to the stories Hound is based upon—the stories of Cú Chulainn are part of a medieval manuscript tradition known as the Ulster Cycle, which are tales that were either written in or primarily deal with the northern province of Ulster in Ireland. These sagas are spread out across various manuscripts and sometimes have several different versions (e.g. TBC has three different “recensions”) that contain conflicting and confusing information. Some of Cú Chulainn’s stories were also expanded upon in Early Modern Irish manuscripts and were heavily focused on during the 19th and 20th century Celtic Revival (or Celtic Twilight) period, the works of which influenced many popular perceptions of Irish myth and folklore in the minds of modern audiences.

As such, I do not claim to know what is the actual “true” story of Cú Chulainn’s saga, but having studied the stories featuring him I wanted to bring in my own experience to talk about what I noticed had been changed for Hound. I won’t be able to speak on certain aspects of the adaptation, given my focus is on literature and martial culture (rather than archaeology or linguistics for example). Here and in the future installments of my scholarly review, I will be including direct references to primary and secondary sources dealing with the story and study of Cú Chulainn.

As a final warning before continuing—this review will have major spoilers for the plot of Hound (and I suppose spoilers for the original myths) so if you would like to read the graphic novel first, then return to the review, now would be the best place to stop. It may also be helpful for following along to familiarize yourself with the stories.

Hound can be purchased here.

Cú Chulainn’s stories can be read on Codecs Van Hamel (type “Cú Chulainn” in the search bar and select “Texts” and you’ll find most of the tales he appears in). I would recommend starting with “The Boyhood Deeds of Cú Chulainn” for this part of the review.

The Conception of Cú Chulainn

In the sagas, the conception and birth of Cú Chulainn bears significant mythical elements that may hint towards some Pre-Christian Irish beliefs. The boy who becomes Cú Chulainn (at birth his name is Sétanta [pronounced shay-dan-tuh]) is seemingly conceived three times and born twice. The Continental Celts (often known as the Gauls) believed in transmigration of the soul, or more simply in reincarnation. The Insular Celtic-speaking peoples (i.e. tribes inhabiting Britain, Scotland, and Ireland) likely shared similar beliefs before the coming of Christianity; the authors of the Compert Con Culainn (hereafter referred to as CCC) may have been aware of such beliefs but likely would not have subscribed to it in their era.

The first incarnation of Cú Chulainn is discovered near Bruig na Boinne (“The Palace of the River Boyne”; in modern day we know this place as the tombs of Newgrange, Knowth, and Dowth) by Conchobar mac Nessa, king of Ulster, and Conchobar’s sister Deichtire after they and a party of Ulster noblemen follow a flock of supernatural birds to the Palace. He is an unnamed, infant son of a mysterious woman living in a home not too far from the Palace who allows the Ulstermen to stay the night as a snowstorm halts them. The following morning, the woman is gone, leaving the child to be adopted by Deichtire who raises him as her own back in Emain Macha, Conchobar’s fortress in Ulster. The boy dies from sickness, however, leaving Deitchtire deeply saddened.

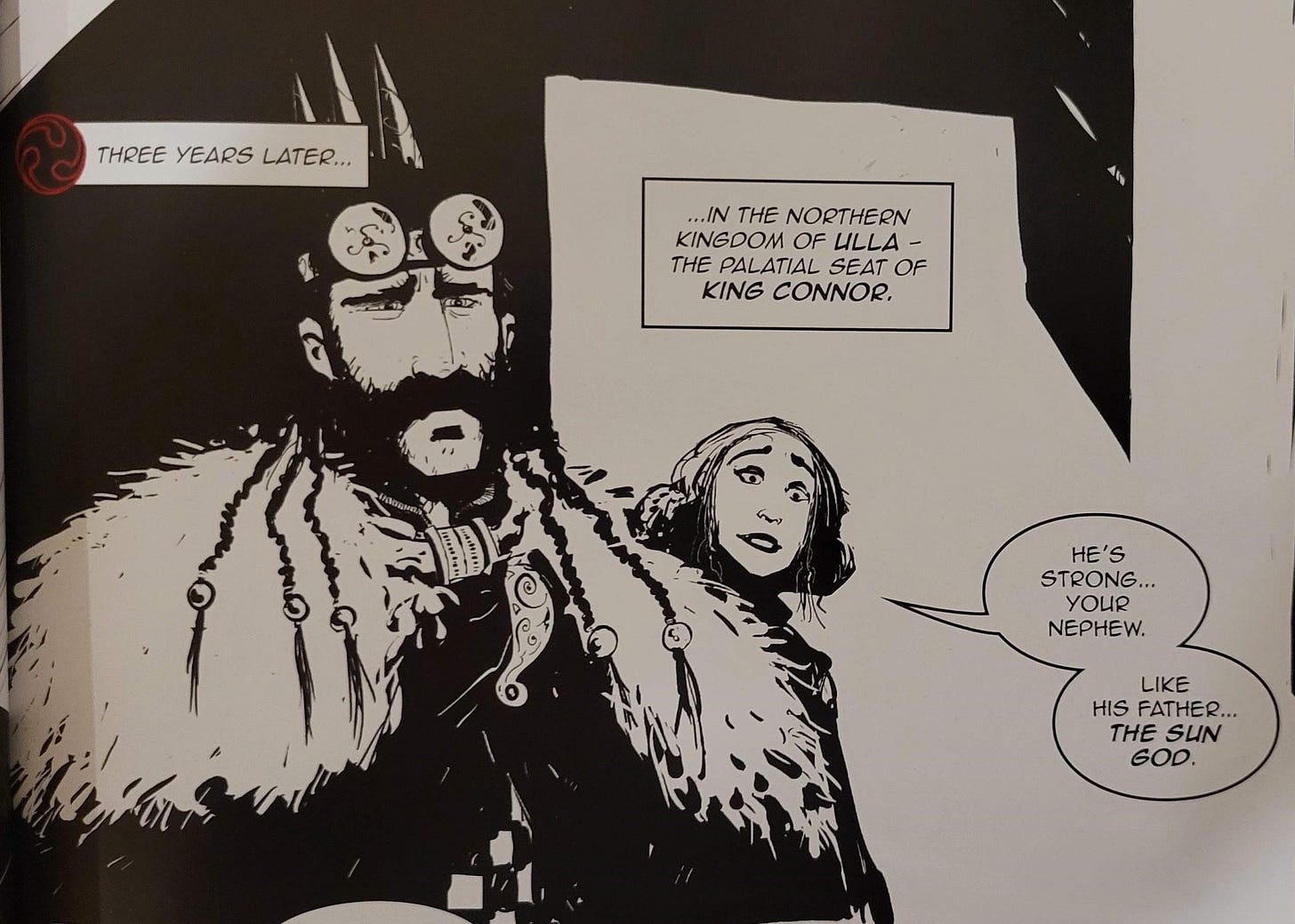

One day, Deitchtire drinks water from a vessel, which, unbeknownst to her, contains a tiny creature that she swallows whole. That night, a beautiful man appears to her in her dreams who claims she is pregnant with his child. This man is Lug, one of the members of the Túatha dé dannan (potentially a pre-Christian god of Ireland). Lug is popularly misidentified as a “sun god”, although there is nothing in the original stories he appears in to indicate that his functions include anything to do with the sun. This misconception is perpetuated in Hound, as Deichtire claims Cú Chulainn’s father is “The sun god.” Lug more accurately embodies an aspect of ancient Irish culture that involves the mastery of skills or crafts; he is also known as the samildánach (“many-skilled”), with those skills being listed in his appearance in the Mythological Cycle1 tale Cath Maige Tuired (“The Second Battle of Moytura”):

[Lug:] ‘Lug Lonnansclech is here, the son of Cían son of Dían Cécht and of Ethne daughter of Balor. He is the foster son of Tailtiu the daughter of Magmór, the king of Spain, and of Eochaid Garb mac Dúach.’

The doorkeeper then asked of Samildánach, ‘What art do you practice? For no one without an art enters Tara.’

‘Question me,’ he [Lug] said. ‘I am a builder.’ The doorkeeper answered, ‘We do not need you. We have a builder already, Luchta mac Lúachada.’

He said, ‘Question me, doorkeeper: I am a smith.’ The doorkeeper answered him, ‘We have a smith already, Colum Cúaléinech of the three new techniques.’

He said, ‘Question me: I am a champion.’ The doorkeeper answered, ‘We do not need you. We have a champion already, Ogma mac Ethlend.’

He said again, ‘Question me.’ ‘I am a harper,’ he said. ‘We do not need you. We have a harper already, Abcán mac Bicelmois, whom the men of the three gods chose in the síd-mounds.’

He said, ‘Question me: I am a warrior.’ The doorkeeper answered, ‘We do not need you. We have a warrior already, Bresal Etarlam mac Echdach Báethláim.’

Then he said, ‘Question me, doorkeeper. I am a poet and a historian.’ ‘We do not need you. We already have a poet and historian, Én mac Ethamain.’

He said, ‘Question me. I am a sorcerer.’ ‘We do not need you. We have sorcerers already. Our druids and our people of power are numerous.’

He said, ‘Question me. I am a physician.’ ‘We do not need you. We have Dían Cécht as a physician.’

‘Question me,’ he said. ‘I am a cupbearer.’ ‘We do not need you. We have cupbearers already: Delt and Drúcht and Daithe, Tae and Talom and Trog, Glé and Glan and Glésse.’

He said, ‘Question me: I am a good brazier.’ ‘We do not need you. We have a brazier already, Crédne Cerd.’

He said, ‘Ask the king whether he has one man who possesses all these arts: if he has I will not be able to enter Tara.’2

The child that Lug magically impregnated Deichtire with is meant to be Cú Chulainn, but her sudden pregnancy arouses suspicion amongst Conchobar’s court. To abate this, she marries a man named Sualdam, but seeing it as improper to give birth to a child that is not her husband’s, she crushes the fetus in her womb, aborting it, and conceives a child with Sualdam. She carries this child to term and names him Sétanta (who will later come to be called Cú Chulainn).

The triple-conception aspect of Sétanta’s birth is absent from Hound. Instead, soon after the prologue, his story begins when he is already around three years old and being doted upon by his mother (whose name is Dierdre in the graphic novel). As mentioned above, his mother simply claims, “His father is the sun god”, showing that Bolger likely chose the second conception for his adaptation. Sualdam is completely absent from Hound and there are no other characters who fill his role in the story.

The location of Bruig na Boinne from the first conception and birth is used in Hound as the place where the Morrigan abducts and brings the toddler Sétanta to. Connor follows her in his “war-wagon”3 to the tombs and retrieves the boy after wounding the Morrigan. Given that Dierdre dies, Connor takes it upon himself to raise Sétanta in her place.

The specific relationship that Hound chose to focus on (that being the connection between Cú Chulainn and the Morrigan) brings the Morrigan into this episode when she—and other supernatural entities that serve similar functions as her—are actually entirely absent from CCC. The choice to features her as part of Cú Chulainn’s very early life was likely to give reason for his violent nature, as she seems to warp his mind while he is her hostage in Bruig na Boinne.

Another major section from CCC is absent in the Hound adaptation of this tale—at the end of the original story, the champions of Ulster argue over who will have the honor of fostering the infant Sétanta, each candidate expositing his skills worthy of instructing the child in during his early years. The judge Morann settles the dispute by assigning each champion a specific area of education and childcare for Sétanta.

Although the sagas of the Ulster Cycle are meant to be set in a much earlier time than when they were written down,4 they feature references to medieval Irish law. The legal system of medieval Ireland is complex and is beyond my area of expertise, however, my research delved deeply into the fosterage system of medieval Ireland. Fosterage in medieval Ireland was the standard custom for childcare and education, where children as young as infants could have been sent to other families to learn and develop skills appropriate to their social status. It was not an institution that served children in unstable familial situations as fosterage is regarded today, but could be more comparable boarding school or extended summer camp managed by families. References to fosterage—and other forms of Irish law—are absent from Hound, limiting the scope of Cú Chulainn’s social circle and drastically altering the relationships he has with characters adapted from the sagas—namely Connor (Conchobar) and Fergus mac Roích. For the benefit of a general audience, it is likely for the best that Bolger left out the intricacies of medieval Irish law, however, leaving Fergus out of Cú Chulainn’s education and development as a young man and hero cripples his character and completely ignores one of the most emotional relationships in Cú Chulainn's life. King Connor instead serves as the primary paternal figure in Hound, which is no doubt one of his key functions in the saga-accurate Cú Chulainn's life.

The Boyhood Deeds of Cú Chulainn

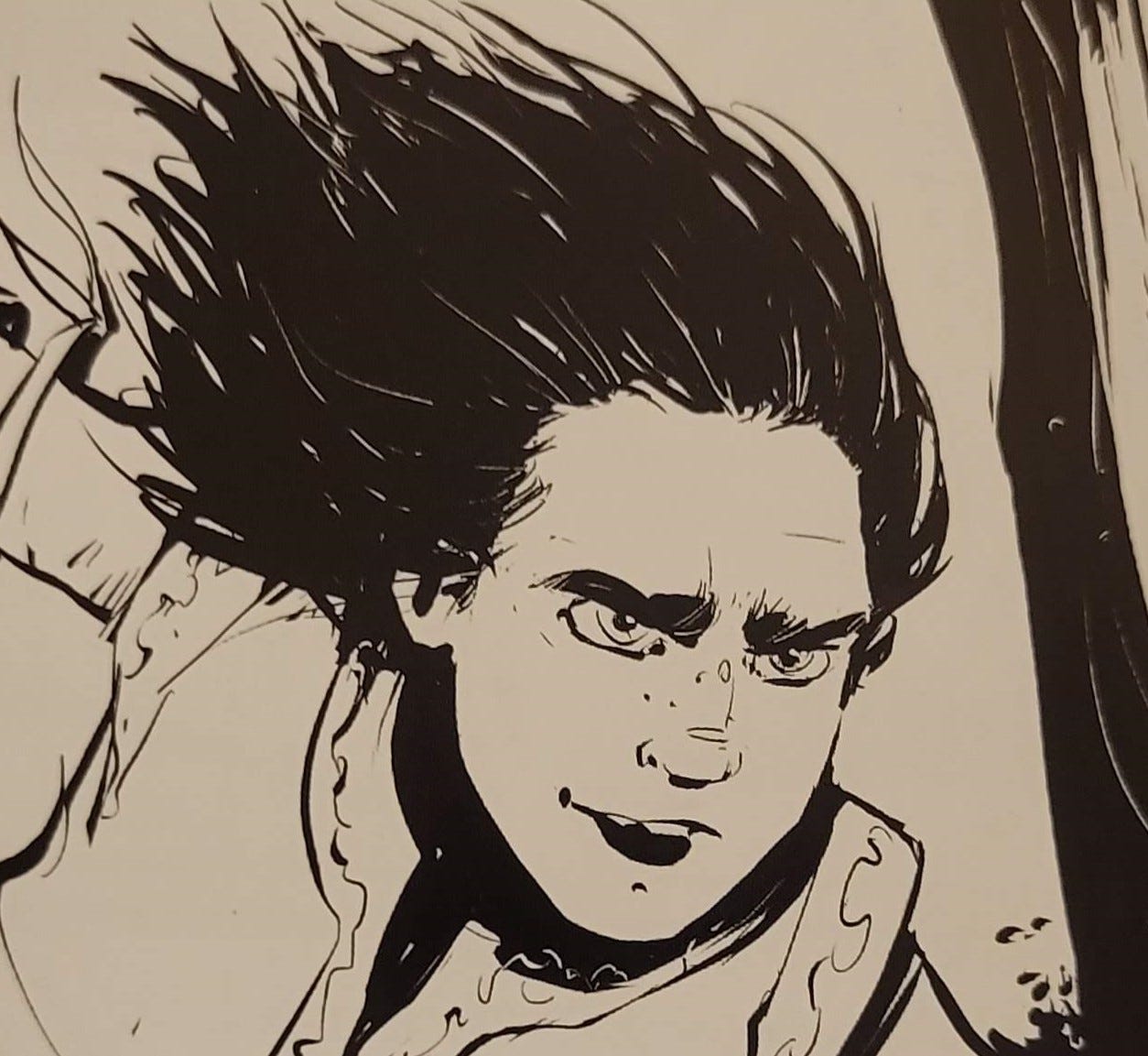

When I started reading Hound I was very interested to see how Bolger would adapt Cú Chulainn’s boyhood deeds. After reading it, however, I can safely say that the graphic novel has a very truncated version of this episode, featuring the “best of” in the boyhood deeds but also missing key elements that I believe really establishes Cú Chulainn’s early relationships and his status as an exceptional hero. Hound’s shortened boyhood deeds play out more like a standard superhero origin story, hitting the standard beats that readers familiar with “cape” stories will recognize, albeit flavored with details from the sagas—a teenage Sétanta being regarded as an outcast by his peers, a prophecy foretells that whoever “spills blood” upon a certain day will be remembered as a famous warrior, and Sétanta acquiring a superheroic identity through a great deed. Understandably, origin stories for heroes—even lesser known ones—can be detrimental to the pacing of the rest of the story, however, Hound unfortunately sacrifices some key details from the Macgnímrada Con Culainn (“The Boyhood Deeds of Cú Chulainn”; hereafter referred to as MCC) that I believe—and point out in my master's thesis—signals his transition from boyhood into manhood.

MCC is narrated during the events of TBC, and mainly deals with the deeds Cú Chulainn performs during his boyhood training at Emain Macha—the seat of power in Ulster, anglicized as “Owen Macha” in Hound—from the age of 5 to 7. At age 5, Sétanta is still living with his biological parents, Deitchtire and Sualdam, in a fort south of Emain Macha and is regaled by tales of the boy troop at Emain Macha. Against his mother's protests to go once he has an Ulster champion to secure his entrance, Sétanta ventures to Emain Macha to play with the boy troop, carrying a kit of play items: “He went off then with his wooden shield and his toy javelin, his hurley and his ball.”5 Once he enters the playing field, the boy troop attacks him for not having a champion to vouch for him:

Then he went to the boys without binding them over to protect him. For no one used to come to them in their playing-field till his protection was guaranteed, but Cú Chulainn was not aware of the fact that this was tabu for them. ‘The boy insults us,’ said Follomon mac Conchobair. ‘Yet we know he is of the Ulstermen. Attack him.’ They threw their thrice fifty javelins at him, and they all stuck in his toy shield. Then they threw all their balls at him and he caught them, every single ball, against his breast. Then they threw their thrice fifty hurling-clubs at him. He warded them off so that they did not touch him, and he took a load of them on his back.

Thereupon he became distorted. His hair stood on end so that it seemed as if each separate hair on his head had been hammered into it. You would have thought that there was a spark of fire on each single hair. He closed one eye so that it was no wider than the eye of a needle; he opened the other until it was as large as the mouth of a mead-goblet. He laid bare from his jaw to his ear and opened his mouth rib-wide so that his internal organs were visible. The champion's light rose above his head.’

Then he attacked the boys. He knocked down fifty of them before they reached the gate of Emain.6

Conchobar, who seemingly had not seen Sétanta since he was an infant, stops the boy in the middle of his rampage and questions who he is and why he is attacking the boys. Conchobar agrees to protect Sétanta from the boy troop, but immediately after releasing him, the little boy attacks his peers again. When Conchobar stops Sétanta again and asks why he’s attacking the boys, he responds by telling his uncle to make him the sole protector of the boy troop to which Conchobar agrees.

Sétanta’s initial conflict with the boy troop is featured somewhat in Hound, but is spun more as a result of a few boys mocking Sétanta and the Morrigan’s influence causing Sétanta to see his peers as monsters rather than a breech of social etiquette as is the case in the original story. Sétanta in Hound is already shown as a member of the boy troop—although there is no direct mention of a “boy troop” in the graphic novel—but is slanted as the “outsider” due to the absence of biological parents and his traumatic experience in Bruig na Boinne. This struck me as a moment of forced dramatization given the fact that fosterage and adoptions were taken seriously in Irish culture and even in Christian times, kinship and social privileges for bastard-born or adopted children were based more on if fathers pesonally recognized their children as worthy inheritors of their social status or deserving of their affection.7

There are several short episodes that follow the introduction of a young Sétanta, which I will skip past in the interest of staying on track.8 The next relevant story is how Sétanta acquires the name Cú Chulainn in the episode titled “The Death of the Smith's Hound.” At the beginning of this tale, Conchobar is visiting the estate of the master blacksmith Culann who agrees to host a feast for the king and some members of his court. Conchobar returns to Emain Macha and sees Sétanta playing three games with the boy troop:

Conchobor went to the playing-field and saw something that astonished him: thrice fifty boys at one end of the field and a single boy at the other end, and the single boy winning victory in taking the goal and in hurling from the thrice fifty youths. When they played the hole-game—a game which was played on the green of Emain—and when it was their turn to cast the ball and his to defend, he would catch the thrice fifty balls outside the hole and none would go past him into the hole. When it was their turn to keep goal and his to hurl, he would put the thrice fifty balls unerringly into the hole. When they played at pulling off each others's clothes, he would tear their thrice fifty mantles off them and all of them together were unable to take even the brooch out of his cloak. When they wrestled, he would throw the same thrice fifty to the ground beneath him and a sufficient number of them to hold him could not get to him.9

Conchobar is amazed by the boy's deeds and comments on how wonderful it is to have such a child in his province. Fergus replies with perhaps one of my favorite quotes from any mythological story, making his neutering in Hound all the more disappointing:

Conchobor began to examine the little boy. ‘Ah, my warriors’ said Conchobor, ‘happy is the land from which came the little boy ye see, if his manly deeds were to be like his boyish exploits.’ ‘It is not fitting to speak thus’ said Fergus, ‘for as the little boy grows, so also will his deeds of manhood increase with him.’10

The Fergus of the sagas is a strong, yet quietly wise character who values honor and heroic values. The Fergus of Hound is a one note character that just hovers by King Connor’s shoulder, acting somewhat as a naysayer but never contributing anything of importance to the plot.

Conchobar invites Sétanta to Culann's feast, but the boy insists on playing longer before he attends. Conchobar goes ahead to the feast and Culann asks if he is expecting anyone else as he plans to release his dangerous hound11 to protect his fields. Conchobar, for some reason, forgets Sétanta is on his way and allows Culann to unleash his hound. Hound adapts this scene in a way that gives a better explanation as to why Conchobar may have forgotten Sétanta was coming—in the graphic novel, Connor arrives at the feast and drinks a lot of wine, thus making him, in his inebriated state, forget that anyone else was following him to Culann's home.

Sétanta arrives on Culann's land after the hound is released and goes to attack the boy, but he uses his driving stick12 and ball to eviscerate the beast. Another version of this scene describes Sétanta breaking the hound's spine with his bare hands. Hound uses the first version, which I believe makes for a more interesting visualization and serves to demonstrate that Sétanta is still a child using a toy to kill a monster.

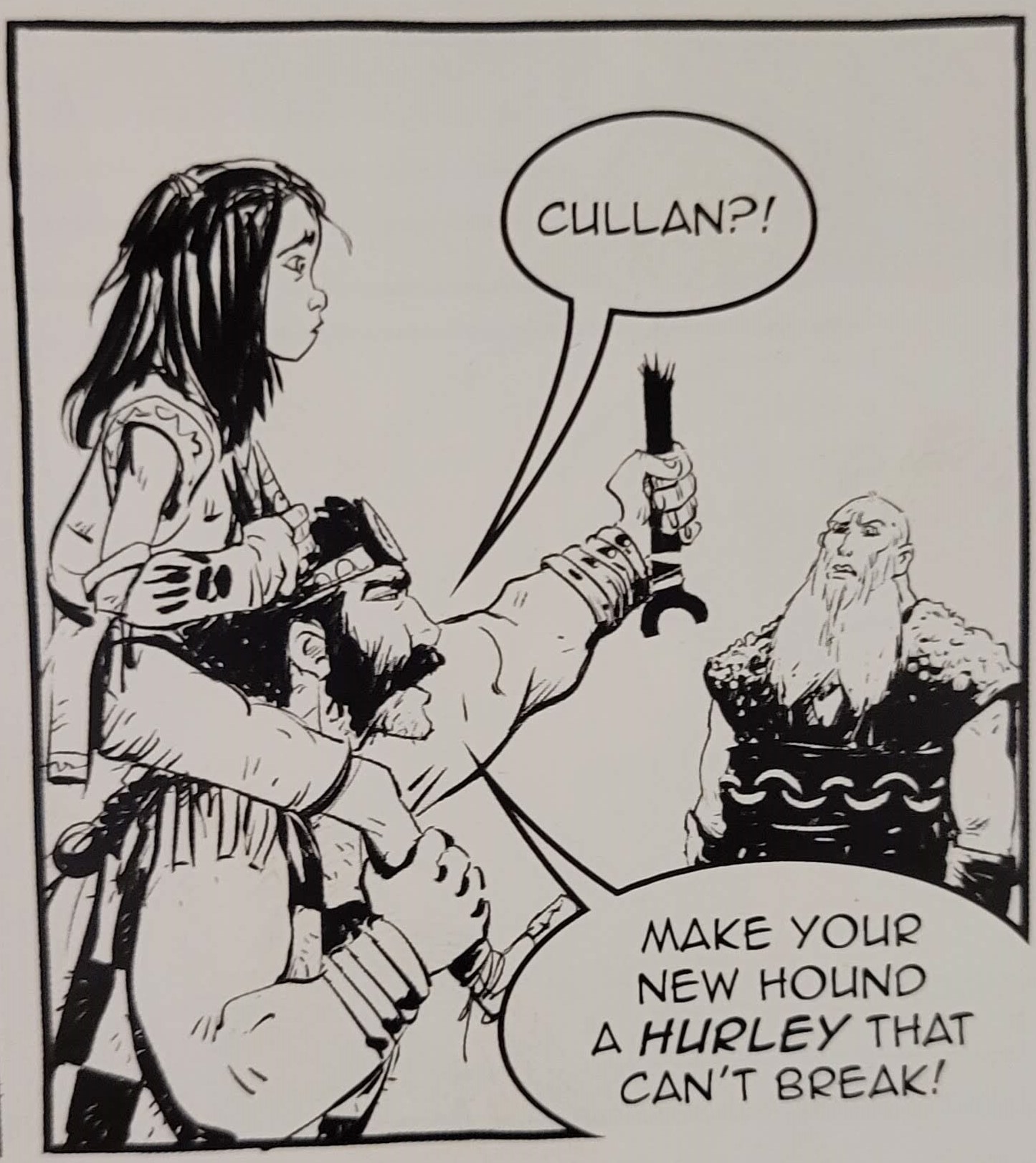

Culann is angered by the death of his hound but Sétanta offers to serve in place of the hound until a new one is reared for the smith. As such, Sétanta acquires the new name Cú Chulainn, meaning Hound of Culann.

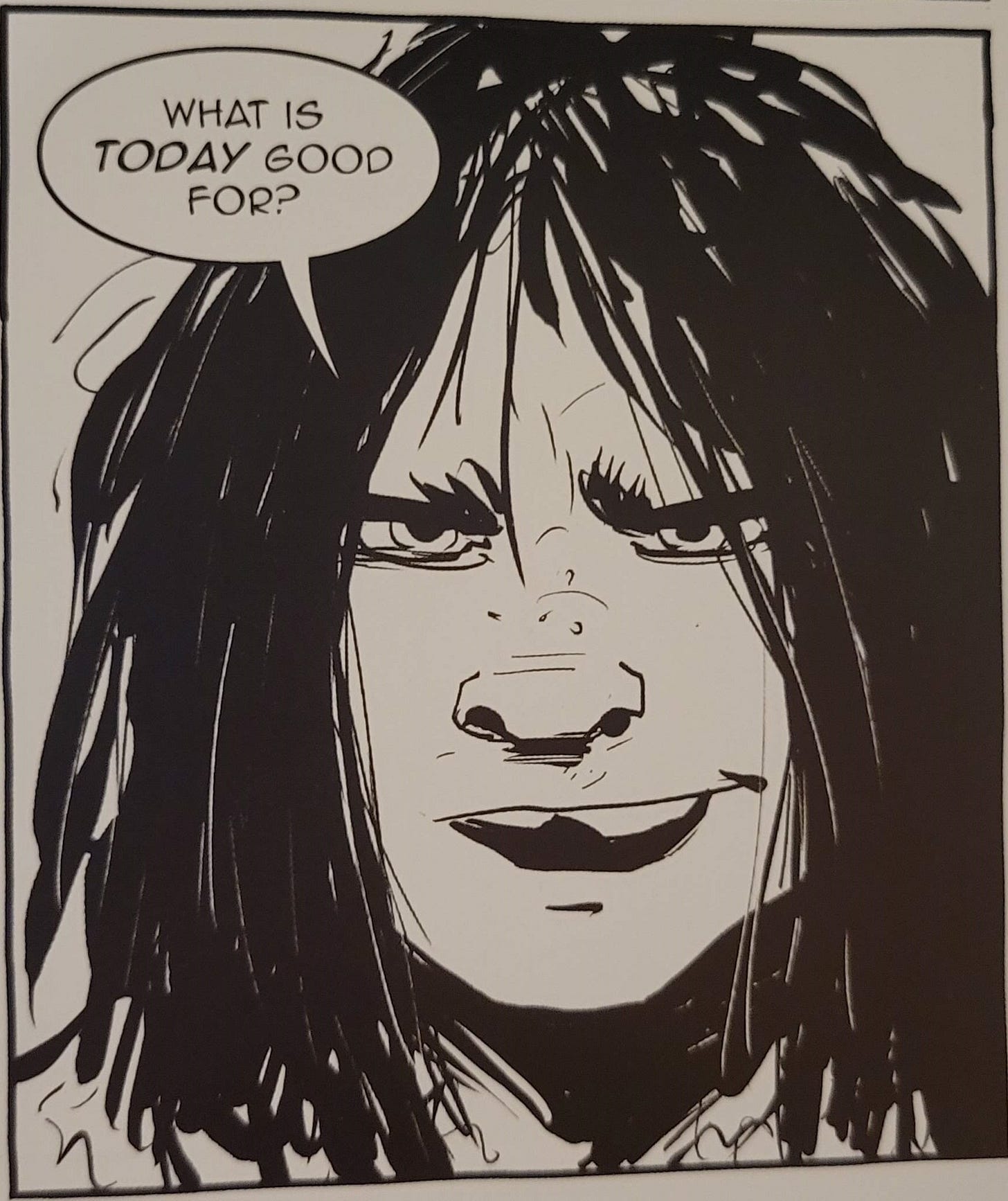

Hound adapts “The Death of the Smith's Hound” episode by combining it with the incentive event of the last episode of MCC, “The Death of the Three Sons of Nechta Scéne.” This part of Hound and the aforementioned episode begin with the druid Cathbad (anglicized to Kava in Hound) instructing his pupils. Sétanta is part of this lesson in Hound but in the original tale, Cú Chulainn13 merely overhears Cathbad while he is playing. After Sétanta's outburst and Connor's invitation, Sétanta asks Kava, “What is today good for?” This question is also asked by Cathbad's pupils in the MCC episode, but the druid's answer is radically different in the source material versus the adaptation:

Cathbad said that if a warrior took up arms on that day, his name for deeds of valour would be known throughout Ireland and his fame would last for ever…‘It is indeed a day of good omen,’ said Cathbad. ‘It is certain that he who takes up arms today will be famous and renowned, but he will, however, be short-lived.’

The grim part of the druid's prediction is more or less the same between the source and the adaptation, but serve different storytelling purposes. Traditionally, Celtic heroes are not long-lived and don’t usually have children, so in lieu of that they have larger-than-life stories to commemorate their deeds, seeking out total danger to make for a better tale should they survive or not.14 Hound on the other hand is more interested in painting the life of Cú Chulainn as a tragedy, which would not be terribly far from some scholarly interpretations of his stories.

An interesting choice that Bolger made is having Cú Chulainn use a weaponized version of his driving stick throughout the story and well into his adult life. In the sagas, Cú Chulainn only uses his driving stick as a weapon when he is a child, up to the point in “The Death of the Three Sons of Nechta Scéne” when he hears Cathbad's first prediction, which is when he throws down his playthings and rushes to Conchobar to ask for weapons befitting of a warrior. I pointed out in my thesis that this was Cú Chulainn’s transitory moment from young boyhood into an older stage of the male lifespan, called gillacht in Old Irish, meaning he is old enough to bear arms but is not yet a full-grown man. I suppose that him wielding his driving stick throughout his life serves as a bittersweet symbol of a boy who dreamt of being a warrior and turned a thing for play into an instrument of destruction and violence. What is more is that Conchobar, in both the original story and the graphic novel, is the one to give Cú Chulainn his warrior kit. In the original episode, he lends Cú Chulainn his own weapons, but in the graphic novel he gives Cú Chulainn’s broken driving stick to Culann, ordering him to fashion it into a weapon.

One of the most distracting parts of Hound was that it did not use the properly conjugated form of “Cú Chulainn” but instead spells it as Cú Cullan. I'm not sure at all what the point of somewhat anglicizing it could be for other than ease of reading.15

Hound completely skips over the section of the episode wherein Cú Chulainn kills the three sons of Nechta Scéne and goes on a hunt in his chariot. It was likely for the interest of focusing the story, but personally I feel like Bolger missed an opportunity to illustrate the following scene in his dark but beautiful style of Hound: “In this wise he went to Emain Macha with a wild deer behind his chariot, a flock of swans fluttering over it and three severed heads in his chariot.”16 “The Death of the Three Sons of Nechta Scéne,” in my opinion, is the major turning point in Cú Chulainn’s development as a young man and hero. In Hound, however, the characters seem to base their praise of the boy mostly off Kava’s prediction of shedding blood and an alleged omen of Cú Cullan accidently making a Red Hand of Ulster symbol on his bracer. Indeed, Connor declares him a hero and for the next 10 years of the story treats him mostly as a star player for team Ulster.

While Hound’s adaptation of the “Boyhood Deeds” did not exactly meet my expectations or show as many “beats” in the young Cú Chulainn’s development as a young man and hero, it still manages to distill the key moments that would be mostly familiar to casual audiences of Irish mythology. As I said above, some of Bolger’s decisions for this adaptation were interesting and impressive, but it seems that Hound is more interested on examining the adult Cú Chulainn. Similarly, I look forward to cross-examining the adaptations of the sagas within the graphic novel.

Read the next part here!

Thank you for reading this first part to my first major scholarly review! Be sure to leave a like and share your thoughts in the comments using the button below!

Spread the lore as well! If you know a friend who loves mythology, Ireland, and graphic novels, refer them to Senchas Claideb using the button below and secure special rewards for yourself including a personalized Gaelic phrase and and original, free short story!

Much like how the Ulster Cycle of tales deals with stories centered around the province of Ulster, the Mythological Cycle’s subject matter is on mythological events and characters which may provide minor insight into the pre-Christian beliefs of Ireland.

Cath Maige Tuired: The Second Battle of Mag Tuired. Translated by Elizabeth Gray. §55-67. https://celt.ucc.ie/published/T300010/

I thought it was interesting Bolger chose to use this term instead of the commonly-used “chariot” in most translations since we don’t have any archaeological evidence of archetypal chariots in Ireland.

The Táin Bó Cúailnge is sometimes referred to as “a window to the Iron Age” which is when most of the Ulster Cycle tales are estimated to have taken place. There are also references to Rome's zenith and the Resurrection of Christ having occurred alongside the events of the Ulster Cycle, but these could easily be later insertions.

Táin Bó Cúailnge (Recension 1). Translated by Cecile O’Rahilly.

Táin Bó Cúailnge (Recension 1). Translated by Cecile O’Rahilly. The monstrous form Sétanta takes is known as the “warp-spasm”, which is not featured in Hound until the very end.

Hound also considerably ages up Sétanta at the start of the MCC adaptation, having him be around the age of 13 rather than 5. This may be another way to streamline the story, but I noticed this also has a snowballing effect in terms of Cú Cullan's age later in the story. This only really something other Celticists would notice, but seeing him carrying out his major life events at a much older age just threw me off a tad.

There is an episode shortly after Sétanta joins the boy troop of Emain Macha where he encounters an Irish war goddess taking the form of a scald crow. She taunts him during a fight to enrage and inspire violence in him, which is also technically the Morrigan’s function in Hound, but there is nothing in the original tales that points to Cú Chulainn having any “curse” or “power” imposed on him by the Morrigan.

Táin Bó Cúailnge (Recension 2). Translated by Cecile O’Rahilly. Sétanta’s excellence in sports is only shown briefly during the episode of his young boyhood in Hound when he plays a little game by himself, striking a ball in the air and trying to hit it again before it lands. It is only in the next part of the graphic novel, taking place 10 whole years later, when his superior skill in sport is displayed.

Táin Bó Cúailnge (Recension 2). Translated by Cecile O’Rahilly.

The original text calls Culann's hound an archú which literally means “slaughter hound” (ar = “slaughter”; cú = “hound”)

Most translations use the word “hurley” to describe the stick Sétanta uses, however the sport of hurling is not attested in Ireland until after the Norman invasion. The original word, lorg ane, means literally “driving stick” and is the term I prefer to use when reciting these stories.

For sake of clarity, “The Death of the Three Sons of Nechta Scéne” occurs after “The Death of the Smith's Hound” so by then Sétanta acquires the name Cú Chulainn.

One of my favorite quotes from Cú Chulainn himself is in the second recension of TBC when he approaches the fortress of the three sons of Nechta Scéne:

‘Is it they who say,’ asked Cú Chulainn, ‘that there are not more Ulstermen alive than they have killed of them?’ ‘It is they indeed,’ said the charioteer. ‘Let us go to meet them,’ said Cú Chulainn. ‘It is dangerous for us,’ said the charioteer.’ ‘Indeed it is not to avoid danger that we go,’ said Cú Chulainn.’

The overall anglicization of names in Hound is something I will return to in a later installment of the scholarly review, but in short it seems to follow the modern Irish pronunciations of words rather than the Medieval Gaelic pronunciations.

Táin Bó Cúailnge (Recension 1). Translated by Cecile O’Rahilly.

Hi! I have been looking forward to your scholarly review of Hound. Your insights are invaluable because you have studied Irish mythology and it's rare to see someone like you. Do you have any favorite adaptation of any mythology, not just Irish mythology?

Yes, I get what you are saying. It’s kind of like when they a movie out of a novel and completely leave out parts of it or change the way in which things happen. Very unsatisfying!