"Hound" - The Scholarly Review III - The Cattle Raid of Cooley, Part 2

The third part to my scholarly review of Paul J. Bolger's dark fantasy graphic novel "Hound"

With how large-scale the original text this section of Hound is based off of, I decided to split it into multiple subsections in order to properly talk about what’s going on in the adaptation. While I will say here that there was a lot of content and entire characters with their own storylines cut out for the sake of focusing this story on Cú Cullan as the protagonist, there is at least one part where the narrow focus is more beneficial for the high emotional impact.

As usual, spoilers for Hound and the original myths will follow. If you haven’t read Hound, I recommend picking it up here, and if you haven’t read my previous installments of the scholarly review you can check out the links to them directly below (in descending order).

"Hound" - The Scholarly Review III - The Cattle Raid of Cooley, Part 1

At last we reach perhaps the most famous story arc from Cú Chulainn’s saga in this adaptation of his life—Táin Bó Cúailnge (“The Cattle Raid of Cooley”). Although the version of events taking place in Hound are heavily truncated from the source material, I decided to split this installment of the scholarly

"Hound" The Scholarly Review II - The Wooing of Emer and Training of Cú Chulainn

I debated at the end of January whether to post this as my first February post or hold off until this Wednesday (Valentine’s Day). I chose the latter option as it a) gave me more time to research and review the relevant sections of Hound, and 2) since the tales we’re examining in this portion have romantic elements, it fit perfectly …

"Hound" The Scholarly Review I - The Conception and Boyhood Deeds of Cú Chulainn

I mentioned in my general review of “Hound” that I might have to split my scholarly review into separate parts. I decided it would be best to do that based on the primary “episodes” that make up the life and saga of Cú Chulainn. This review will be examining Paul J. Bolger’s

Cú Cullan’s Duels and Deepening Madness

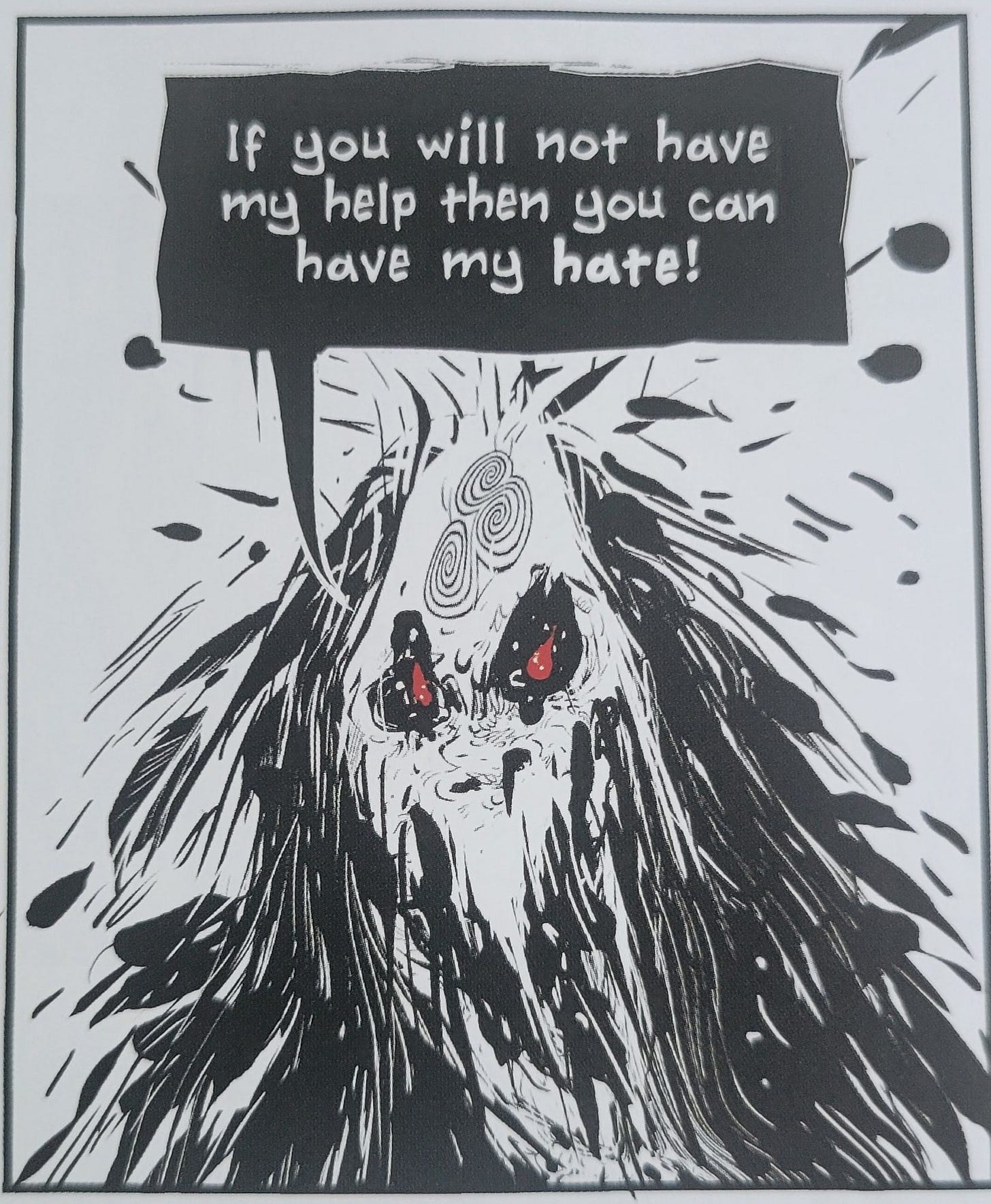

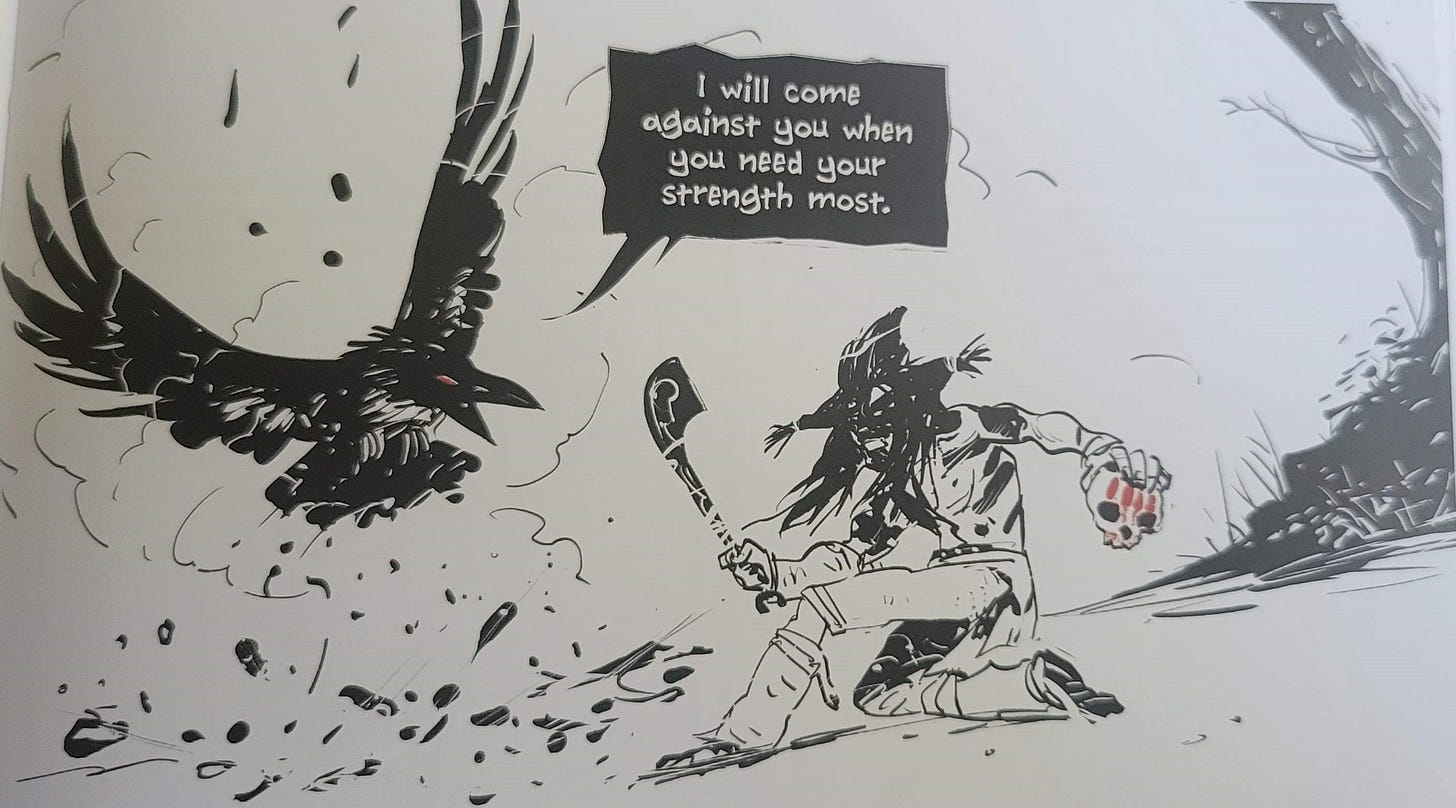

Following the close encounter with the entirety of the Connacht army, Cú Cullan is harried by the Morrigan, who also tries to seduce him, offering great help in return for him laying with her. He rebukes her, and in response she says, “If you will not have my help then you can have my hate! I will come against you when you need your strength the most.”

This scene is an abbreviated but faithful adaptation of the episode in the Táin Bó Cúailnge where Cú Chulainn encounters the Morrígan in the form of a beautiful young woman. When he asks why she has come, she answers, “‘I have come to you for I fell in love with you on hearing your fame, and I have brought with me my treasures and my cattle.’”1 Cú Chulainn, however, is not tempted by her offer and rejects her, leading to this exchange between them (format edited for clarity):

‘It will be worse for you’, said she, ‘when I go against you as you are fighting your enemies. I shall go in the form of an eel under your feet in the ford so that you shall fall.’

‘I prefer that to the king's daughter,’ said he. ‘I shall seize you between my toes so that your ribs are crushed and you shall suffer that blemish until you get a judgment blessing.’

‘I shall drive the cattle over the ford to you while I am in the form of a grey she-wolf.’

‘I shall throw a stone at you from my sling so and smash your eye in your head, and you shall suffer from that blemish until you get a judgment blessing.’

‘I shall come to you in the guise of a hornless red heifer in front of the cattle and they will rush upon you at many fords and pools yet you will not see me in front of you.’

‘I shall cast a stone at you,’ said he, ‘so that your legs will break under you, and you shall suffer thus until you get a judgment blessing.’2

The variations from this to Hound are in the exact offer the Morrigan gives Cú Cullan and the mention of her attacking him in the forms of different animals. In the graphic novel, she simply offers him “the love of a goddess” and does not harry him much during the cattle raid after this encounter.

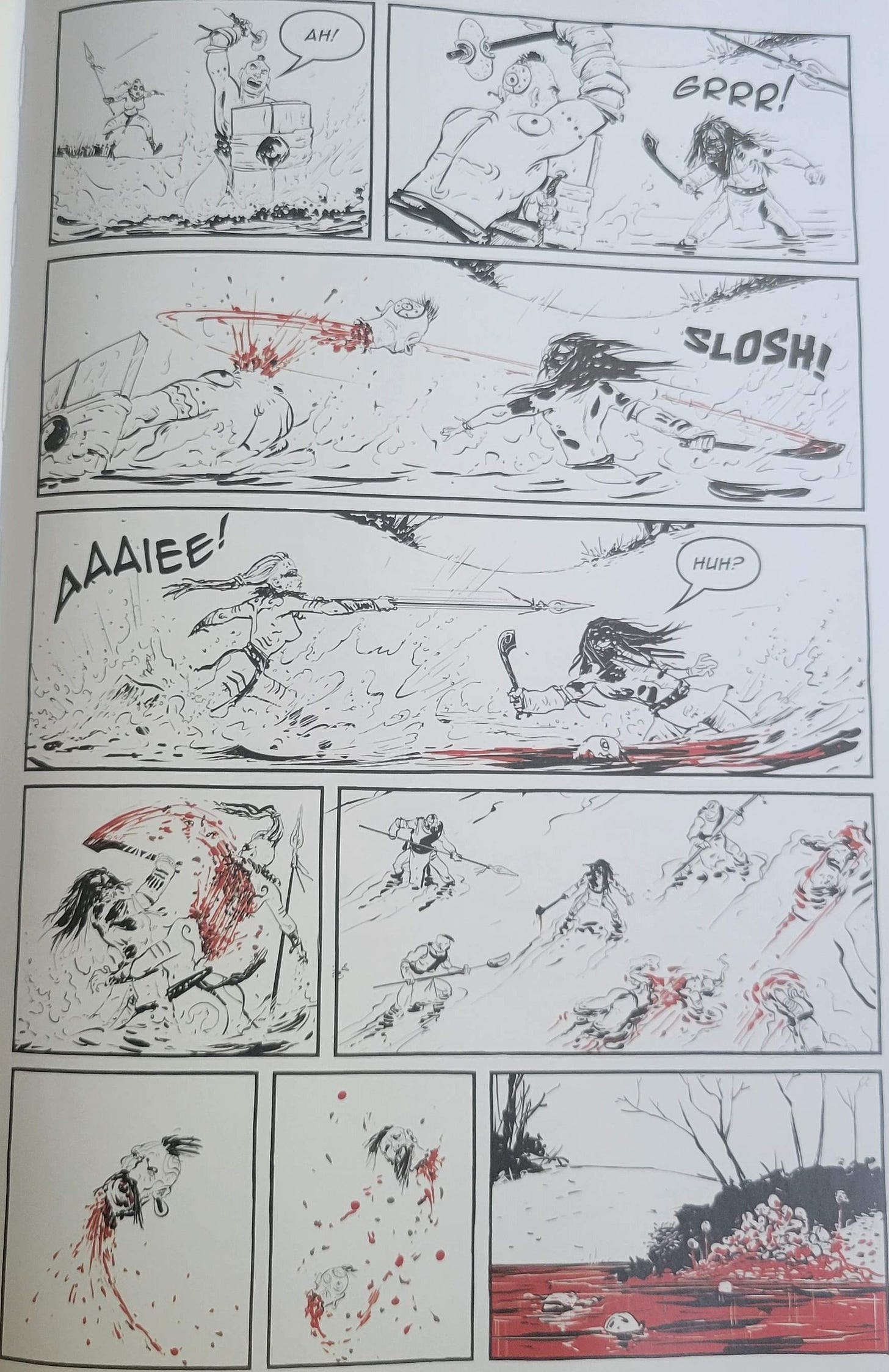

What follows is an extremely truncated version of the many duels Cú Chulainn wages to slow the advance of the Connacht army. None of Cú Cullan’s opponents are named in Hound during this section as they are in TBC. During one duel, Cú Cullan is suddenly beset by the battle-lust induced by the Morrigan and is distracted by a demonized version of Maeve. His present opponent wounds him in the chest and soon after, the Donn Cúailnge whisks him to safety. This part was definitely made up for the graphic novel as there is no episode in TBC where Cú Chulainn and the Brown Bull ever meet.

After the Bull ferries Cú Cullan away, he wanders through a snowy forest, nursing his wound and arguing with the Morrigan. In the middle of his walk, he chances upon several children collecting firewood. The Morrigan’s tampering with his mental state causes him to view the children as demons and he attacks them. While this scene may feel gratuitous, I wonder if Bolger was trying to emulate or at least add the gravity of how in TBC there is an episode where the entire boyhood troop of Ulster, which includes Cú Chulainn’s friends, are killed when trying to face the Connacht-men.

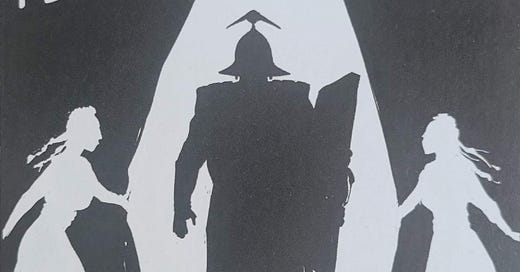

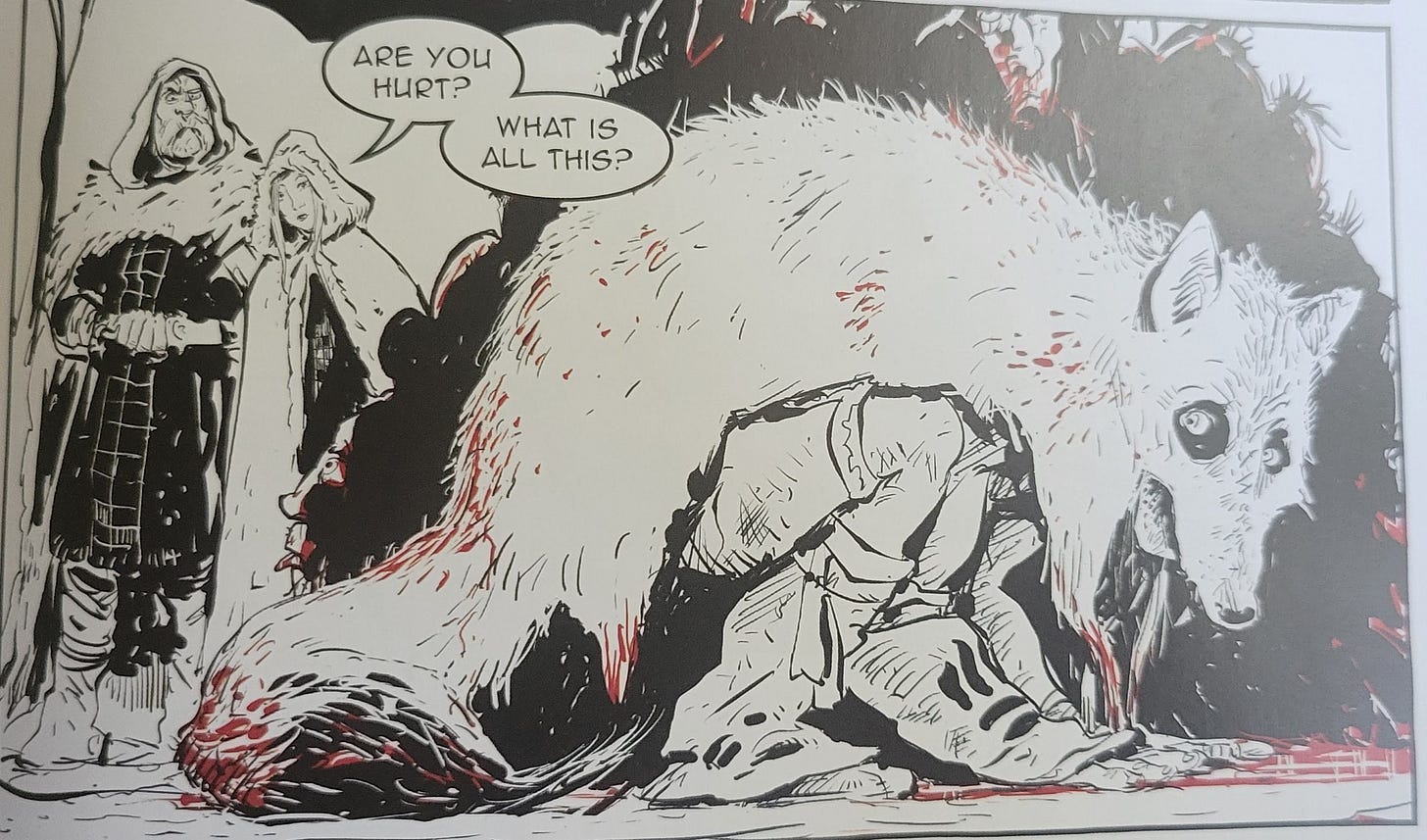

Shortly after, Cú Cullan seems to go mad, donning a wolf skin cloak and creating a mound of severed heads in the woods from men and women. He claims that their deaths are sacrifices in hopes that the Morrigan will stop haunting him. Emer and Fergus come to find him as his absence leaves Ulster open to attack from the Connacht-men, but he proclaims he is done with fighting. This part punctuates the anti-war message both Hound and TBC stand for.

The Fight of Ferdia and Cú Cullan

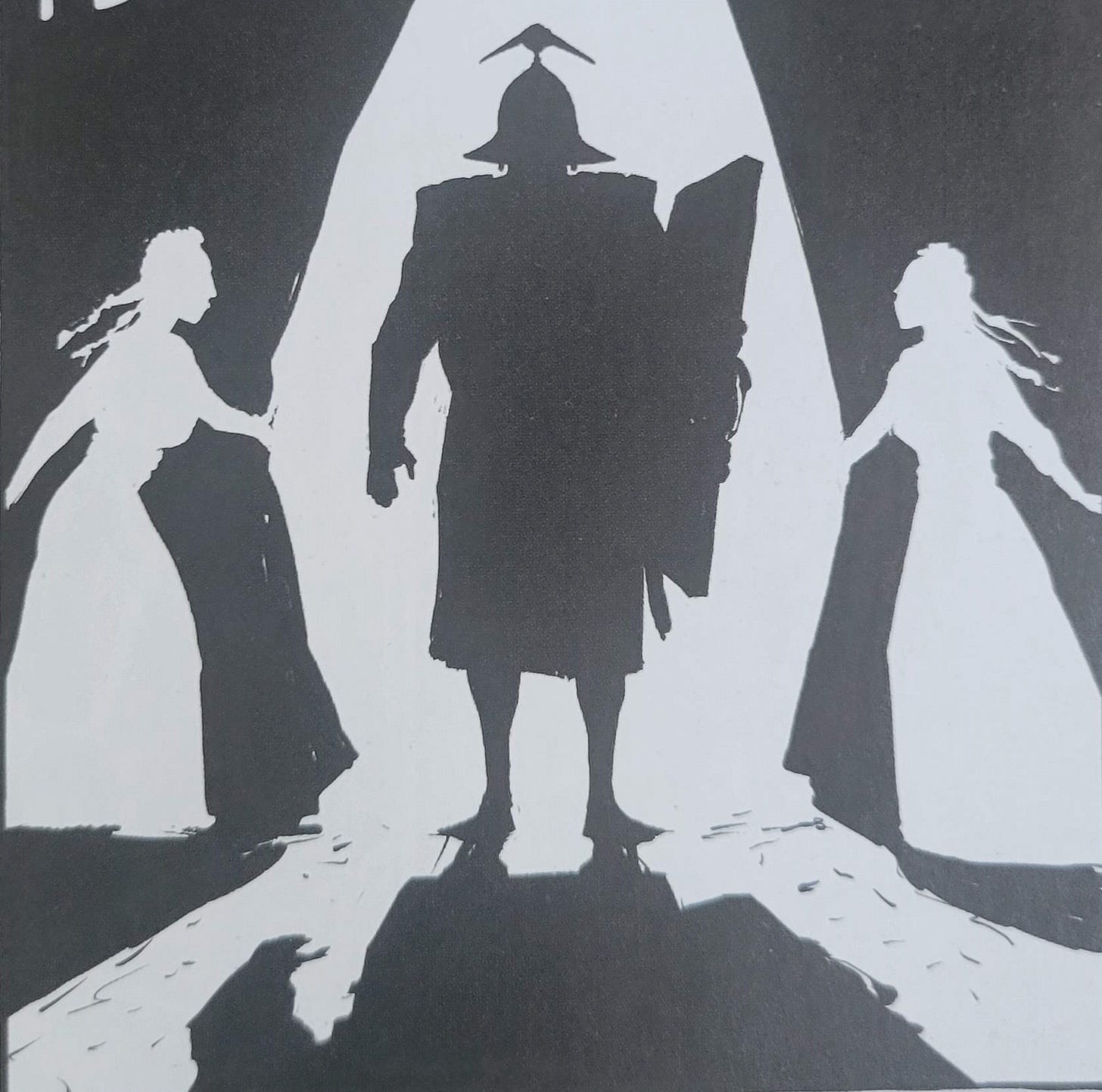

Later, Connor seems to have mostly recovered from the Morrigan’s poison and musters his personal army, the Red Branch, to meet Connacht on the ford they are held up at. Maeve comes to bargain with Connor, offering to set up a duel between Ferdia and Cú Cullan that will determine the outcome of the raid. Maeve offers to retreat should Ferdia win. Cú Cullan is obviously reluctant to fight but agrees at last. Before the fight Kava performs some kind of ritual that is meant to block out the Morrigan’s influence over Cú Cullan. Ferdia prepares by donning a suit of armor, helm, and a large millstone over his chest. In TBC, Cú Chulainn is said to wear a special raiment to control his rage:

Of that battle-array which he put on were the twenty-seven shirts, waxed, board-like, compact, which used to be bound with strings and ropes and thongs next to his fair body that his mind and understanding might not be deranged whenever his rage should come upon him.3

My advisor in grad school, Ranke de Vries, who specializes in medieval medicine, likens the shirts to a sort of “straightjacket” that may partially subdue Cú Chulainn during his “warp-spasms”. Kava’s incantation in Hound may be a stand-in for this attire. Cú Cullan never actually uses his “warp-spasm” during the Cattle Raid section, but is inhuman rage definitely stems from the Morrigan’s influence.

Ferdia in TBC, meanwhile, is described as having a conganchnes (“horn-skin”)4 that wards off any blow. It is uncertain if this refers to Ferdia’s actual skin or if it is a type of armor made from hardened materials. The millstone in Hound may be a variation of it or is specifically worn by Ferdia as an attempt to prevent the Gae Bolga from piercing him.

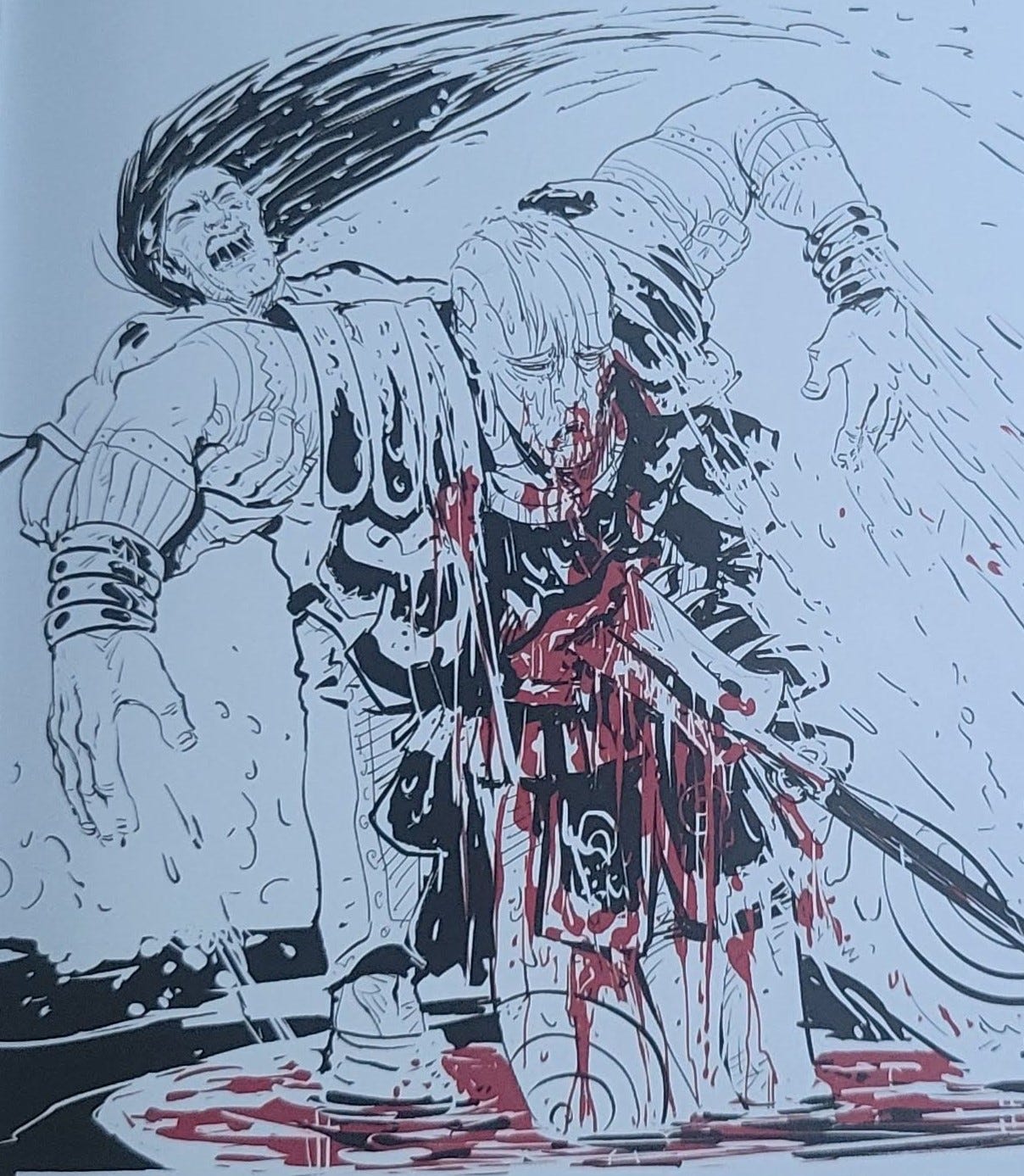

The friends meet at the ford, watched by the armies of Connacht and Ulla. Cú Cullan rushes into battle on a chariot, armed only with the Gae Bolga and his weaponized playing stick. During the fight, Cú Cullan recites Kava’s incantations to keep the Morrigan at bay, confusing Ferdia. In the middle of the battle, Ferdia says, “Poets will sing of when a wolf and hound fought for three days…”, likely referring to how long the original fight between Cú Chulainn and Ferdia took to wage; at the end of each day, they would come away from the ford with increasingly more gruesome injuries. Their duel in Hound, however, is resolved soon after as Ferdia gets ahold of the Gae Bolga and hurls it at Cú Cullan (although it was established only he could wield it being the son of “the sun god”). The Morrigan’s influence skews Cú Cullan’s mind for a moment and he kicks it back at Ferdia and it pierces him, breaking the millstone as well.

For all the parts of TBC that were left to the wayside in adapting Hound, this part overshadows all the “cut content.” One decision that Bolger made, which was likely the right move for telling this particular story, was by emphasizing the raw dread and emotion Ferdia and Cú Cullan had when fighting each other. Originally, Medb persuades Ferdia to fight Cú Chulainn by offering generous amounts of treasure, land, and her own daughter’s hand in marriage. Ferdia rejects all of these and Medb makes up a rumor claiming Cú Chulainn boasted about being able to best Ferdia. In the context of medieval Irish culture, this would be a grave insult worthy of renouncing a friendship over as demonstrating honor and strength was paramount to the warrior-elite. In Hound, however, Bolger chooses to focus on the almost lack of autonomy Cú Cullan and Ferdia have as pawns in a larger war; Cú Cullan’s leaders reinforce that he is their defender and champion doing right by fighting for his province, at the same time building up Ferdia as a “wolf” that is only meant to attack. In the end, Cú Cullan denounces the propaganda he has been fed, understanding that nothing has actually been won from the conflict and that he only paid greatly for his hand in it.

The End of the Cattle Raid

Following Ferdia’s death, Ulla and Connacht come to an uneasy truce with the only dissenter being Calatin (the Morrigan in disguise). Connor welcomes Cú Cullan back into his court by returning his cloak and pin. Cú Cullan, now more than ever, wishes to be rid of the Morrigan’s influence and tries asking Connor for information, but the king claims ignorance. Connor as well, cannot seem to understand Cú Cullan’s sadness over the loss of Ferdia, as he simply sees it as part of war or simply “business.” Amidst Connor’s pep-talk, reminiscing about celebrating after killing his enemies, Cú Cullan firmly states, “Ferdia was not my enemy.” Bolger made a very interesting choice by having Ferdia’s death as the final duel and deciding factor of the cattle raid as in TBC, Cú Chulainn ceases fighting for the rest of the story to mourn his friend, allowing Connacht to invade and pillage Ulster before being driven away by Conchobar and his champions, released from their debility. Instead, a grim sort of peace (or lull of conflict) prevails, but Cú Cullan is not able to celebrate it with his best friend. In fact, Maeve does not even acquire the Donn Cúailnge, making her invasion against Ulster and the lives lost even more pointless. In the original story, Medb takes the Brown Bull but it ends up killing Findbennach and receiving mortal wounds; it wanders back to Dáire’s farmstead and dies. Both stories get across the futility and horrors of war (although TBC has far more slaughter than Hound), but Hound particularly drives home the cruel fact that lives and friendships were lost due to an agent of senseless war.

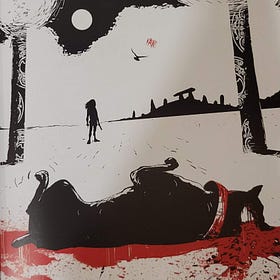

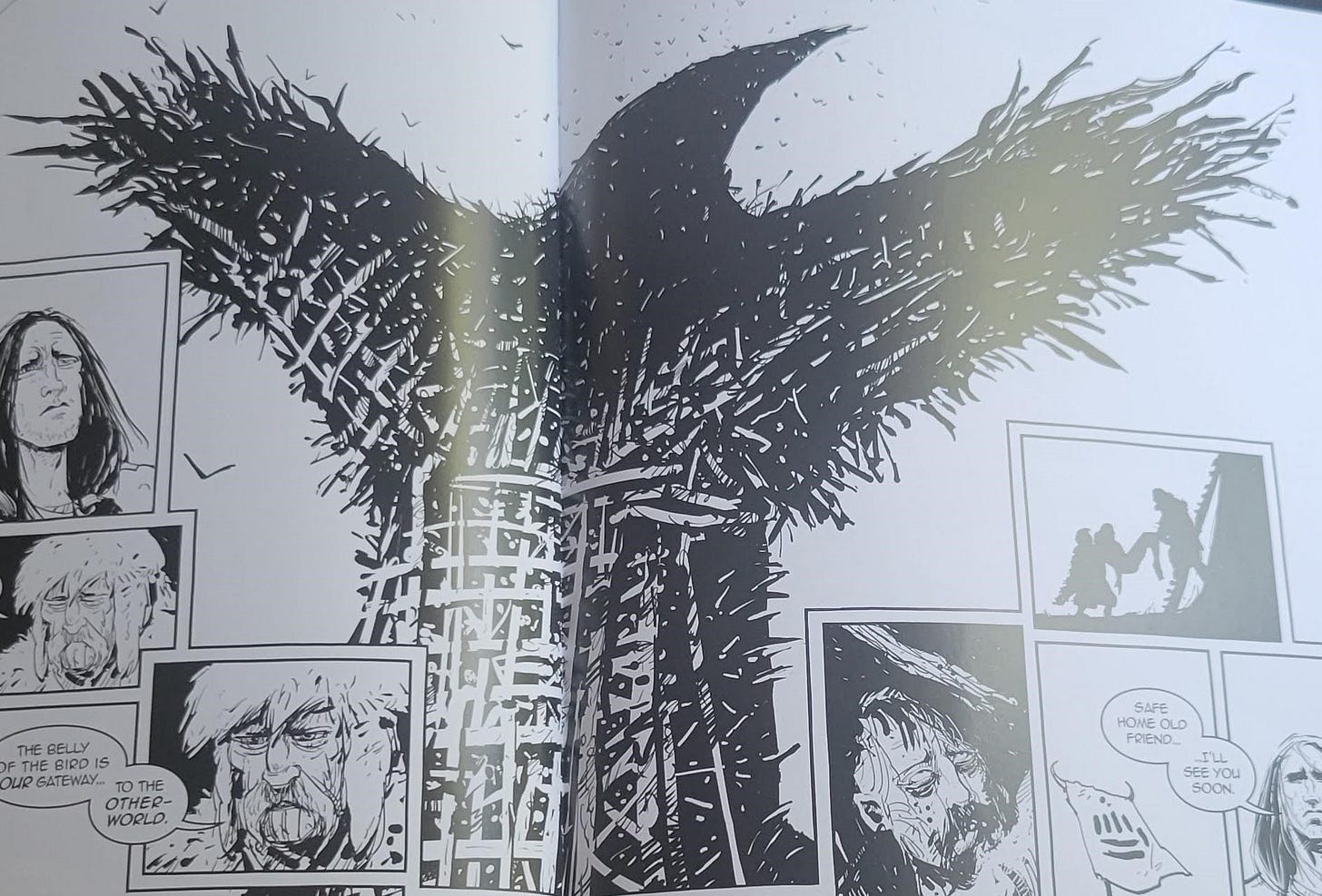

Cú Cullan has a wicker man-like funeral pyre built in the shape of a crow, containing not only Ferdia’s body but the bodies of others killed in the cattle raid. He lights it himself and declares to the crowd of people from Ulla and Connacht, “If any of you gathered here spark the flame of war again, know this…I will hunt you down and rain fire on you like never before. Do you hear me?!! You saw me make war…don’t have me make peace.” This part illustrates one element of Cú Cullan’s character that seemed quite paradoxical the first time I read Hound, which is his unceasing conflict between wanting to be a warrior and wanting absolute peace. With the significant time jump after his boyhood deeds and right before he meets Emer, he seems to have some crisis of identity somewhere in between

Overall Thoughts

Although I’ve reiterated that I was initially disappointed that the Cattle Raid of Cooley segment of Hound cut out a lot of the original elements that made it a much broader epic, in hindsight it makes sense for Bolger to have pared down the original story in order to focus on Cú Cullan’s personal struggles and the overall anti-war thesis of the graphic novel. Although TBC itself is grim and gruesome all the way through, but somehow—perhaps thanks to its visual medium—Hound seems to dial up the dark elements, even if some of them slip into “edgy” territory. The section where Cú Cullan seemingly goes mad confused me somewhat, but again makes sense for the kind of story Bolger wanted to tell.

The strongest part of this chapter was most definitely Cú Cullan and Ferdia’s fight. In the spirit of the source material, this scene is one of the emotional high points of the story. Bolger uses it to great advantage, punctuating the inner struggles of Cú Cullan manifesting in his physical world and the overall thesis of Hound. Irish heroic stories tend to be tragic and present lessons about the dark side of vying for immortal glory whether the original authors intended it or not, and Hound illustrates this by challenging notions of war, martial culture, and heroism. He demonstrates the fine line Cú Cullan walks of being both protector and destroyer in his role as champion of his province. Although his fight against Ferdia puts an end to the raid, Cú Cullan loses and kills his own friend. It is a tragedy that is rarely discussed in popular discourse of Irish heroes, when they are even discussed at all.

Read the next part here!

Thanks for reading this week’s post! How do you feel this part compared to the original story? Share your thoughts in the comments!

Refer your friends to Senchas Claideb and receive special rewards, including a personalized Gaelic phrase and a free, original short story!

Follow me on other social media platforms!

Táin Bó Cúailnge Recension 1. Translated by Cecille O’Rahilly, 2011. §1849-50. https://celt.ucc.ie/published/T301012/index.html.

TBC Rec. 1. O’Rahilly (trans.).

TBC Rec. 1. O’Rahilly (trans.).

eDIL s.v. conganchnes.

I especially like your summation in which Cu Cullen wants only peace— not war, ever again. If only that could be the way of our world now!m

I'm glad to read more of your scholarly review of Hound this month! I thought you were saving it for later since you said you would dedicate this month to Sword & Planet.

How many parts are left in your scholarly review of Hound? Do you plan to treat the death of Aífe's only son and the death of Cú Chulainn in separate parts?