"Hound" - The Scholarly Review Part V - The Death of Cú Chulainn

The final installment of my review of Paul J. Bolger's dark fantasy graphic novel

At long last, we come to the concluding installment of my first major scholarly review of a Celtic-themed piece of media. The reason it took me so long to get this out is owed mostly to the fact that I am not as familiar with Cú Chulainn’s death-tale as other stories pertaining to him. I also wanted to get my hands on the latest translation of the story by Bettina Kimpton. If you want a copy of it for yourself, you can grab one here.

As usual, there will be spoilers for both Hound and the original myths that inspired it, so if you haven’t read it yet, you can pick up a copy from Dark Horse Comics’ store.

If you haven’t caught up on my reviews for Hound, I’ve finally put them all in this handy index so I didn’t have to keep posting each individual link in the intro:

The death of Cú Chulainn in art and other media created long after the Ulster Cycle is usually steeped in extreme melodrama. In the case of the Celtic Revival movement especially, it is utilized as a patriotic symbol often standing for either the noble struggle of the Irish or the downfall of the perceived “Golden Age” imagined by Revivalists. While the story does have a tragic nature, the death-tales of Irish heroes are a genre that would likely have been a norm rather than a twist. The fairy tale image of a hero riding off into the sunset or settling into an easy life after many trials and tribulations is not something that would have been so greatly remember in a Medieval Irish audience. In fact, one may look to other world mythologies to find the gruesome ends of heroes that are nowadays considered national icons in different countries’ storytelling traditions.

To be recognized as a hero in Irish literature means to have a good death, meaning one that will be immortalized as a tale in addition to a wealth of stories that will serve as a legacy rather than offspring. Cú Chulainn’s death is no different in terms of being memorable, but is also extremely tragic as it portrays his province in mourning of the loss of their greatest champion. The tale, titled Brislech Mór Maige Murthemni (“The Breach of Mag Murthemne”; hereafter referred to as BMM), follows Cú Chulainn’s downfall as an invading army led by the sons of men he killed in the events of the Tain Bó Cúailnge (“The Cattle Raid of Cooley”; hereafter referred to as TBC) breaches Ulster. Despite efforts to hold him back from fighting, Cú Chulainn enters the battle as sole protector of Ulster, ill-prepared and heedless of omens foretelling his doom. This story, like many other medieval Irish tales, is steeped in cultural nuances, tie-ins to Christianity, and laced with more than a few complex poems.

Hound’s take on the death-tale is a pared-down version of the story, much like how the other chapters have been up to this point. As with the whole of the graphic novel, the story is centered on Cú Cullan specifically. This chapter (aside from the TBC adaptation) was probably the one I had the most conflicted personal and scholarly opinions about. On the one hand, I understand that this piece is Bolger’s passion project and he adapts the Irish sagas to be somewhat more approachable with timeless themes of struggling with humanity’s violent inclinations—which are somewhat extant in the source material. On the other, I feel as though there are some important details that were omitted that harms the narrative and emotional pay-off of Hound.

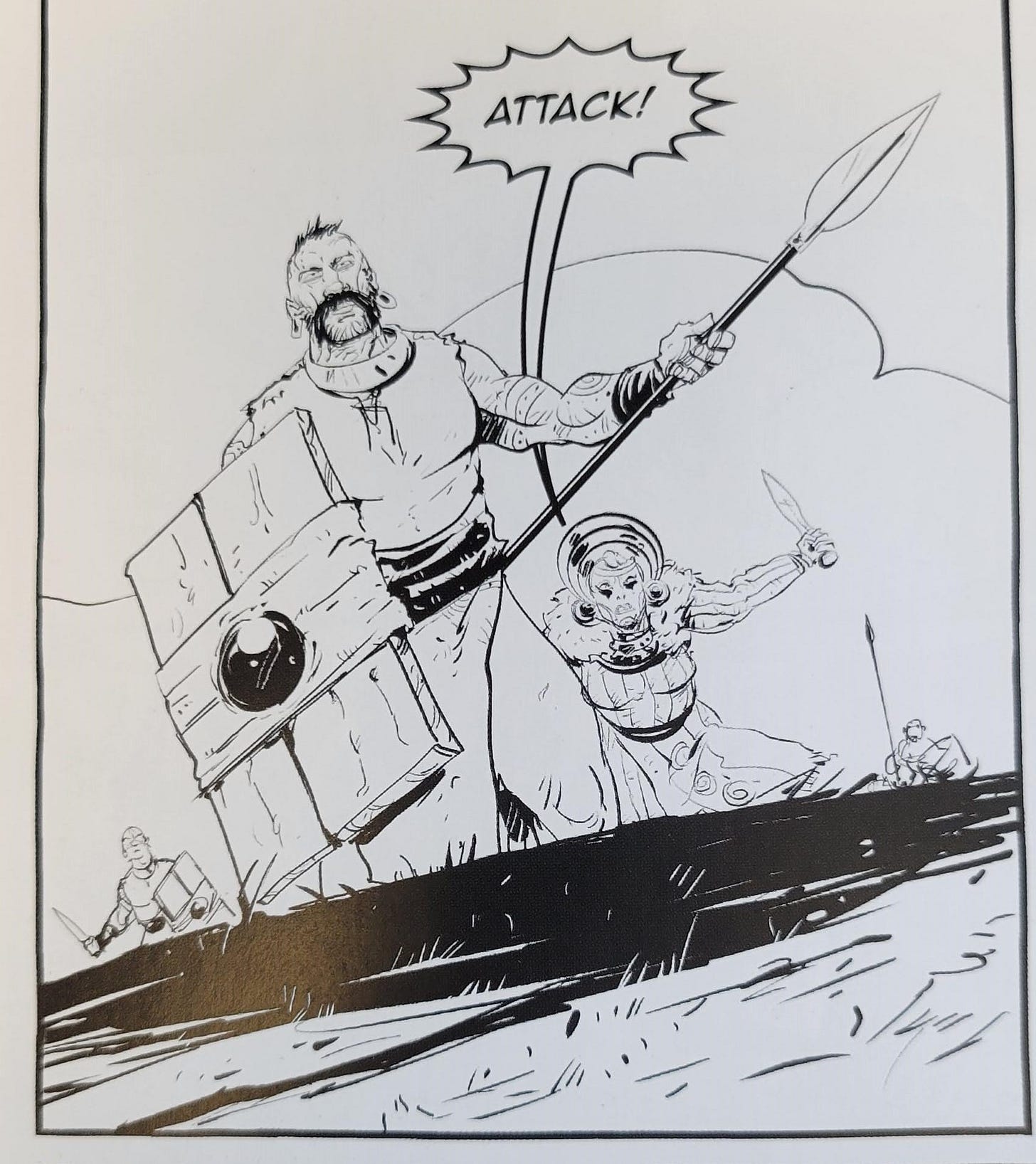

Revenge

In BMM, Cú Chulainn meets his death when invaders from other parts of Ireland raid his home province of Ulster. This troop is led by Lugaid son of Cú Roí, Erc son of Cairpre, and the sons of Calatín.1 The theme of revenge-killing in the name and honor of a family member or friend is prevalent in, but not exclusive, to Gaelic sagas. It is a cycle of violence that was permitted in some cases by Irish law, or at least in popular perception of heroes and champions. Said cycle is on full display following Cú Chulainn’s death when Conall Cernach,2 another great Ulster hero and Cú Chulainn’s foster-brother, avenges him by killing and taking Lugaid’s head.

Hound fixates on Maeve, queen of the province Connacht as the leading human antagonist who wants revenge against Cú Cullan rather than sons of the men he killed during the TBC chapter. This leads to a very awkward ambush scene later on where Maeve and several warrior henchmen jump Cú Cullan’s wife Emer and just simply leave after Cú Cullan breaks up the fight. What would also cause whiplash to someone who read BMM before this is that the fighting during the conclusion doesn’t even take place in Mag Murthemne (Cú Chulainn’s territory in Ulster), rather it takes place at the passage tombs at Newgrange.

Omens of Doom

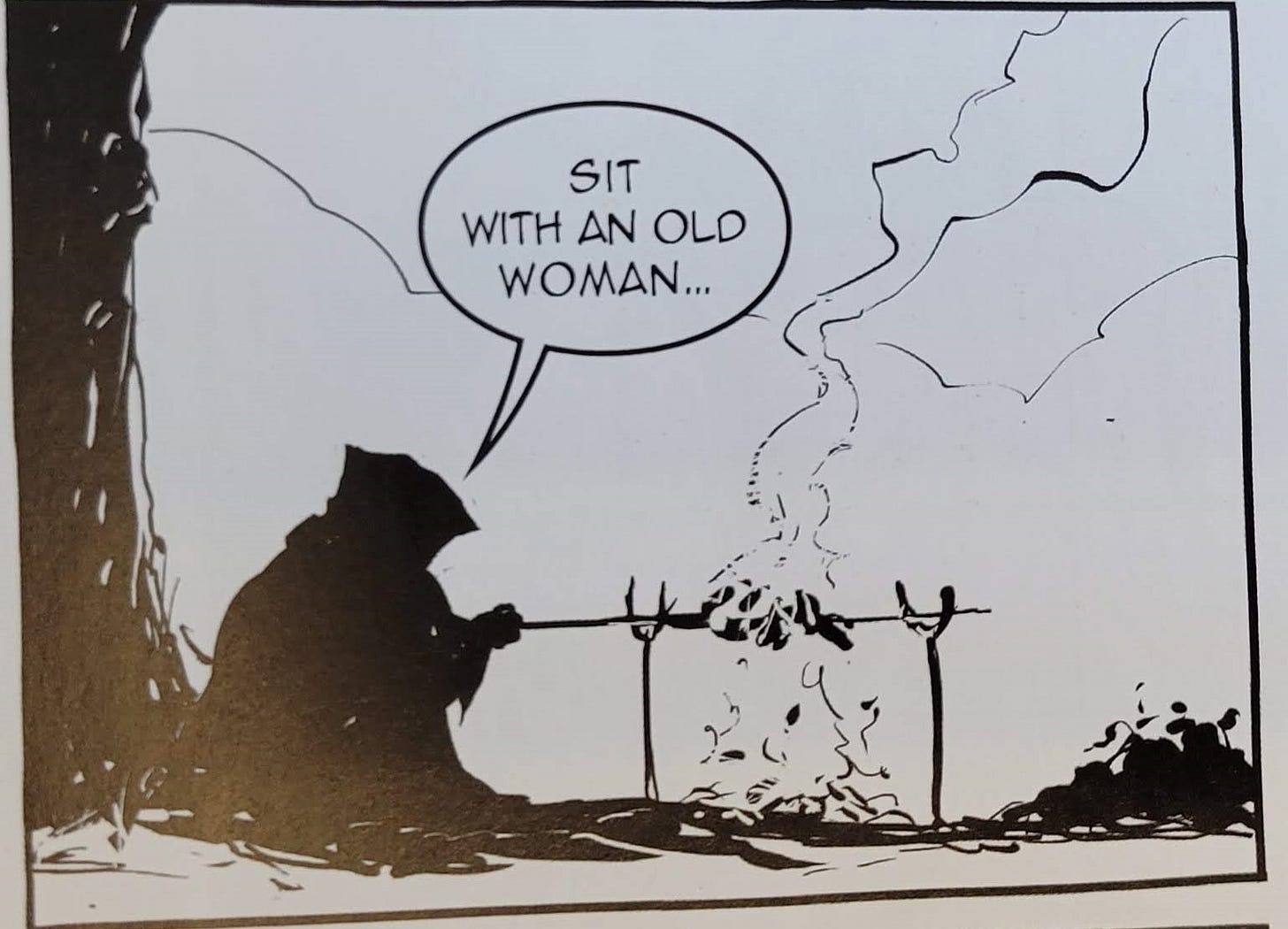

There are two main portents in Cú Chulainn’s death-tale that lead to his demise. One of those is the breaking of his two geasa, which forbid him from refusing hospitality and consuming dogmeat. This comes to pass as he encounters three witches, blind in their left eyes and roasting a hound over a cooking pit, on his way to meet the raiders. Although, in just the previous section, he foretells his doom is near when he runs into those three, half-blind witches, he is coaxed to partake in the forbidden meat when they challenge his geas and honor as a great hero, saying, “He who doesn’t endure or accept something small isn’t capable of anything great.”3 Cú Chulainn comes to a compromise where he accepts the witches’ invitation, but he puts the meat under his left thigh, causing him to lose his strength on his left side.

The other portent are three spears prepared by the sons of Calatín, which they claim “A king will fall by.”4 Lugaid throws the spears between skirmishes Cú Chulainn has with his men, killing Cú Chulainn’s charioteer Lóeg (called the king of charioteers), mortally wounding Líath Macha (one of Cú Chulainn’s horses, dubbed “king of horses”) and Cú Chulainn (dubbed “king of chariot-fighters”).5

Aside from these, almost everyone who Cú Chulainn interacts with tries to keep him from meeting with the invading host, but with personal honor, the threat of satire, and acceptance of his death at the forefront of his mind he goes to battle anyway. Everything prior to his fight with the invaders signals that his end is near, even his horse, Líath Macha (“The Grey of Macha”), refuses to be yoked to his chariot initially.

In Hound, the Morrigan quite literally makes up and lies about what will bring about Cú Cullan’s downfall. She paradoxically wants him to give into her but also seems to have no qualms about killing him outright. Concerning his geasa (or bonds as they are called in the graphic novel), she explains them to Maeve (as Calatin) and claims she “just made them up.” Hound also repeats a popular, erroneous detail concerning the encounter with the witches by having Morrigan be the witch who tricks and weakens Cú Cullan. Understandably, Bolger likely wanted to keep his adaptation focused on Cú Cullan’s relationship with the Morrigan, but in doing so leans into some misunderstandings about her character and completely misses the fact that even the real Morrigan in BMM did not want Cú Chulainn to go to battle.6

The “three spears scene” is equally baffling as in the middle of fighting Cú Cullan and the warriors from Ulla, she mentions, “the prophecy of three spears for three kings” out of the blue. After receiving of volley of spears, Morrigan throws one of them back at Kava whom she proclaims “King of the druids.” The second spear, however, pierces and kills Emer. When Cú Cullan angrily questions Morrigan about this, she claims, “I lied.”

You could remove both of these portents from the last act of Hound and there would likely be no noticeable difference in how things play out. Despite their prevalence in the original source material, geasa are never once mentioned in Hound. Traditionally, these taboos or conditions were placed on heroes and kings as a way to keep their behavior in check. Breaking them would spell a tragic end to the person possessing them, and as such they almost always end up being broken in death-tales. Rather than having them be part of the culture and world of Hound and relegating them to something god-like entities could just “make up” felt somewhat tacked-on to me. It was as if Bolger knew he needed to include the detail about what leads to Cú Cullan’s death but could not find a neat place to insert it into the narrative.

The “three spears” moment, while feeling tacked on given neither Lóeg nor Líath Macha7 appear in Hound does make sense in some ways when looking at the possible analysis of Cú Chulainn’s death being a tripartite death. In the course of BMM, he loses his charioteer and his horses, essentially putting him at his weakest (already hindered by breaking his geas). In Hound, Kava and Emer were the only two “voices of reason” that had any effect on coaxing Cú Cullan away from the Morrigan’s influence, without them, he is on his own in facing her possession.

The Death of a Hero

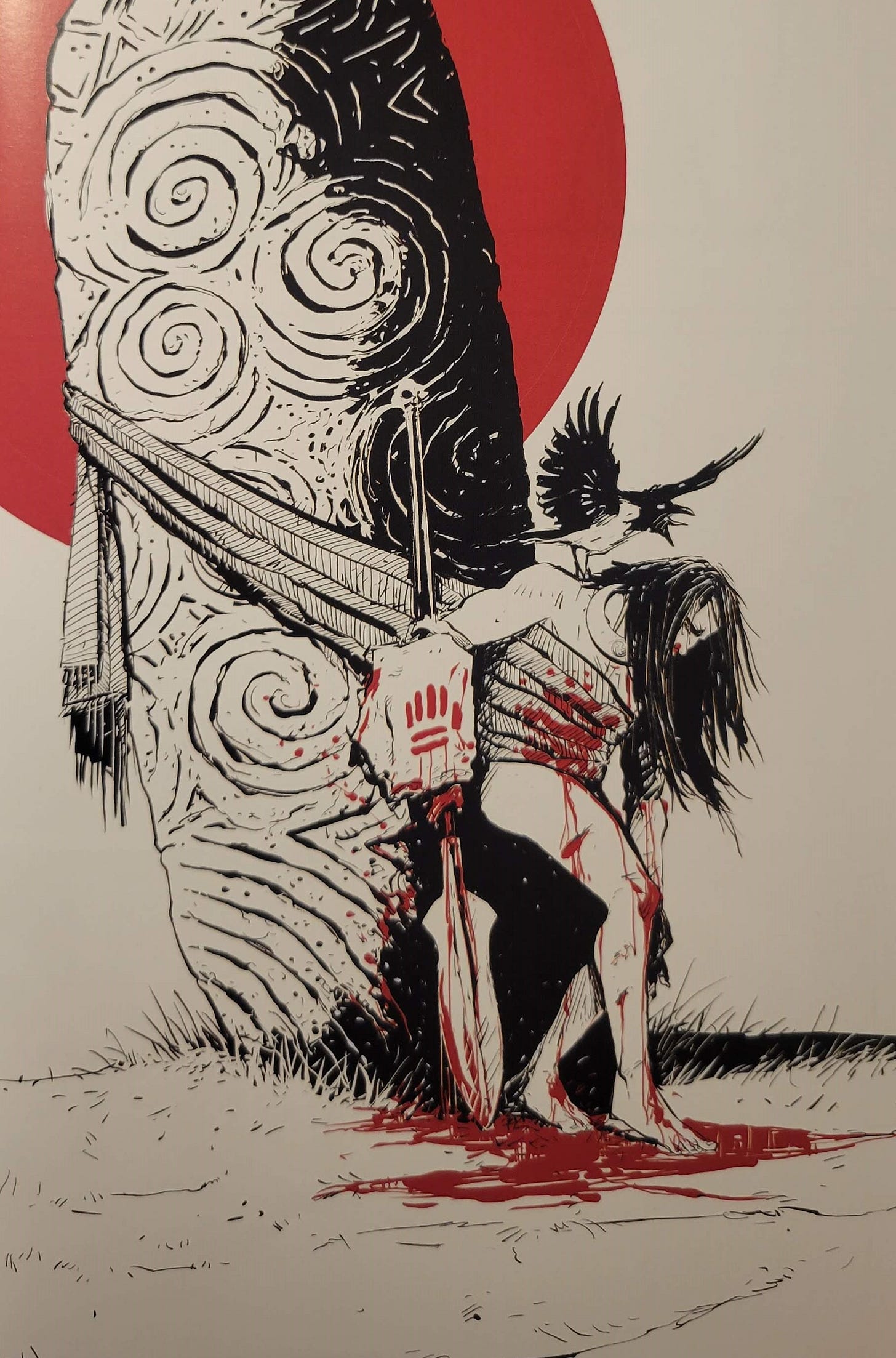

Cú Chulainn, in the original tale, dies after slaying hundreds of invaders before being pierced by the third spear prepared by the sons of Calatín thrown by Lugaid’s hand. He ties himself to a pillar stone to die standing and is comforted by his horse, Líath Macha until he dies. His death is only apparent when a scald crow lands on his shoulder, but even then most of the surviving invaders are to fearful to approach him. Lugaid at last cuts off his head and Cú Chulainn’s corpse cuts off Lugaid’s arm in turn. Angered, Lugaid also cuts off Cú Chulainn’s arm in retaliation.

After Conall Cernach avenges Cú Chulainn and returns to Ulster, Cú Chulainn reappears as a phantom riding a chariot through the sky and prophesying Christianity and St. Patrick’s arrival in Ireland. He also compares himself to a lamb and claims his father, Lug, “was everywhere in every form.”8 Moments like these are plentiful in Medieval Irish literature where the authors were prone to finding ways to canonize their native traditions and characters into Christianity.

Hound echoes some of the imagery of Cú Cullan dragging and tying himself to a pillar stone after a harrowing battle to protect the people he loves. His enemy in Hound, however, is the Morrigan rather than the sons of men he killed. He faces her in the passage tomb where she had taken him as a toddler where he seemingly gives into his violent nature, undergoing the riastrad (“warp-spasm”). The depiction of the warp-spasm in Hound is probably one of the strongest illustrations in the whole graphic novel. It is an abstract, horrific version that seems more spirit-like than flesh but is nonetheless gruesome to witness as glimpses of a bulging eye, crooked teeth, and swollen muscle flash momentarily throughout the panels. Although the warp-spasm seems deliberately avoided in BMM, it is still a fascinating take on Cú Chulainn’s monstrous form. It was moments like these, that I admittedly haven’t dwelt on in my reviews, that I feel could really define a new aesthetic for Irish-inspired fantasy that goes beyond the neutered Victorian depictions of faerie and CW Channel-styled Young Adult novels infecting social media. It is a primeval, terrifying visual of the monster that also protects.

With Hound distancing itself from any Christian themes by trying to portray an Iron Age Ireland, there is obviously no scene of Cú Cullan foretelling Christ’s coming in a phantom chariot. However, themes of pacifism and unity are not as absent as Connor bids for a peaceful, united Erin (Ireland) under the flag of the Red Hand of Ulster.9

The Grieving of Ulster

The original death-tale of Cú Chulainn does not end after he dies, as mentioned prior, his foster-brother Conall Cernach avenges him by killing Lugaid. The whole of Ulster mourns for the loss of their provincial hero. Emer especially is heartbroken and can only see a bleak future without the man whom she was equal with. She laments the downfall of such a mighty warrior at the hands of half-blind witches, worsened by the fact no help came to him.10

In Hound we do not have a prolonged episode of mourning. Emer, as well, dies before Cú Cullan so we never get a long, emotional lament poem commenting on the state of a world without her beloved husband. Instead, Morrigan somewhat usurps that role by leaving the audience with a message concerning the futility of humans committing violence against humans. She also issues a somewhat cavalier challenge to the reader concerning “someone else’s songs of Setanta” if the story “did not ring true for you or went against what you think you know of [her] world…” While it does not entirely seem like Bolger is trying to say Hound is the “definitive” edition of the Ulster Cycle, it did feel like a bit of a bold move especially when it came time for me to crack down on reading between the lines.

Closing this book

Something I had to remind myself during and after my reading of Hound, and consistently throughout my reviews, is that this is an adaptation meant to execute a specific vision the author had. I have heard many theories about the Irish sagas and folklore, from casual enjoyers to rigid scholars, and each person draws out their own meanings or truths from the texts. I get a strong sense that Bolger wanted to strip down the saga of Cú Chulainn to its elemental parts, or at least the themes he felt like exploring. In doing so, he divorced it from many of the medieval Christian tellings of the saga, but also lost a great deal of other cultural nuances along the way. Perhaps the medium of a standalone graphic novel is not the ideal place for a one-for-one adaptation of a sprawling storytelling tradition with innumerable characters each with their own body of tales from a people and era greatly removed from our modern conventions of entertainment and art. The absence of concrete mentions of traditions like fosterage, revenge killing in honor, and geasa tied to a hero’s life and honor removes Hound a bit too much from its own Irish source material. While a lot of what we find in the original literature most likely was more implicit for an audience who understood such concepts and customs, it did sway the story into being somewhat generic dark fantasy at times.

While Hound is not the adaptation I expected (or certainly would have made myself) it is still worth reading if you are interested in modern media inspired by Celtic mythology. It is a start in terms of breaking from the stereotypes that often come packaged with fantasy and fiction concerning the Celts, as it portrays its characters as actual humans rather than nature-loving warrior hippies who can do no wrong. The story is not without its flaws, especially in the eyes of a Celticist, but it at least takes one of the many possible readings of Cú Chulainn’s saga, a critique on war and violence, and presents it in a manner that surpasses the Celtic Twilight interpretations that are wont to permeate popular culture and thought. Overall, I’m glad I came across Hound and gave it a thorough look-through. You might find some truth in it or simply find it entertaining, but it may at least inspire you to look at the older tales.

Thank you all for reading this final installment of my first scholarly review for a pop culture piece! Let me know what you thought of Hound if you’ve read it yourself yet! Are there any pieces of media inspired by Celticism I should look at for my next reviews? Leave them in the comments!

Refer your friends to Senchas Claideb to receive access to special rewards, including a personalized Gaelic phrase and a free, original short story exclusive to top referees!

Shoot me a message!

If you like what I do, consider leaving a tip!

Readers who have read Hound or followed along with my reviews may recognize the name Calatin as the one used by Morrigan in the guise of a Fomorian hag. No such character like the hag in Hound appears in the original sagas, but I did not make the connection until I read BMM.

Conall Cernach is one of the many characters from the sagas left entirely out of Hound. While he is an interesting character, it would be out of the scope of this review to talk about him and the function he has within the original tale. I do recommend reading fellow St.FX graduate Emmet Taylor’s thesis on Conall Cernach, however, which is perhaps the most comprehensive analysis of the character we have to-date.

Cú Chulainn’s Death: A Critical Edition of Brislech Mór Maige Murthemni. Bettina Kempton (translator and editor): §13. Original Irish: “‘Ní túalaing mó nad ḟulaing nó nád geib in mbec.’”

BMM. Kempton (trans): §20, 22, and 24.

Another issue I had with Hound that I’m only realizing now is that Cú Cullan never rides a chariot. While Cú Chulainn is shown to be able to hold is own on foot, a title like “king of the chariot-fighters” ought to be some indication of where he is most dangerous.

BMM. Kempton (trans): §9. Text: “And the Morrígan had dismantled the chariot the night before because she didn’t want Cú Chulainn to go to battle. She knew he’d never return to Emain Macha.”

King Connor’s “war-wagon” in Hound is shown as having two horses yoked to it, one a lighter color (white in the art style of the graphic novel) and the other black, which may be a reference to Cú Chulainn’s horses Líath Macha and Dub Sainglenn (a black horse).

BMM. Kempton (trans): §38.540. Original Irish: “‘Cach cruth cach leth -robae.’”

What is somewhat ironic is that it is possible Cú Chulainn’s original death-tale, which I’m unsure if Bolger was aware of, could have been a propaganda piece authored by the Uí Néill dynasty, which originated in Northern Ireland. The Uí Néill family famously vied for the high kingship of Ireland (which never actually existed), going as far as to declare many of their overlords as High King, when in really they just controlled a bunch of territories and tribes.

The biggest reason Cú Chulainn has no help in BMM is due to the fact that, since Ulster is being invaded, all the men suffer the Debility of the Ulstermen, which causes them to experience pains similar to those of when a pregnant woman goes into labor for a span of nine days, although it is shown as going on for longer in TBC.

I just went through and reread all of your Hound reviews, this was so interesting to follow and a lot more in-depth than I could have imagined! Amazing work.

Congratulations on finishing your scholarly review of Hound! I am looking forward to seeing more of your posts on Celtic mythology and Celtic-themed media!