Using Celticism in Sword & Sorcery

A "How-to" on Using Obscure Mythology and Folklore for an obscure Fantasy Subgenre and a Sneak Preview of January's Short Story

European mythology is one of the most prominent influences on the modern fantasy genre. For better or worse, writers have taken and simplified many concepts from myth and folklore to suit their stories and secondary worlds. Celtic myth and folklore are some of the more misunderstood traditions used for fantasy stories. This is likely due to the scarcity of material available to general audiences and the complex nature of the material that is available. I know that I didn't quite “get” a good deal of Celtic Studies until I undertook my postgraduate program led by some of the leading scholars in the field. Even before then, I knew I wanted to write fantasy stories inspired by Celtic mythology. The problem I ran into during my earliest attempts was being able to sort what we actually understood about the myths as opposed to fantasy narratives invented by internet gurus. I was not exactly aware of those kinds of pitfalls or academic integrity as a younger writer, and as a result, many of my past projects contain inspiration from odd assortments of online blogs, Wicca books, and truncated versions of saga tales. What is really important, I’ve learned, is understanding that many of these tales come from real traditions held by real people, some of whom are still alive and hold fast to the idea that some of the events in the stories could have happened.

As with most world mythologies, the stories of Celtic-speaking1 cultures are usually presented in simplified versions for the sake of delivering in school lessons but lose the fascinating nuances that make the stories—and the cultures they came from—unique. Celts and Celt-like cultures are often stereotyped in fantasy as “barbaric” and nature-loving. The people and creatures of the Celtic Otherworld are always labelled as “fae” (or fey) and usually divided into specific “courts” based on seasons or the conception of Seelie and Unseelie fae, and they are a number one target for edgy Young Adult fantasy novels and tabletop roleplaying campaigns to have “sexy and mysterious” characters. What is more is that usually Celtic-inspired media might also have other cultural myths grafted onto it due to lack of available information (or drive) for authors to research this obscure field (see The Iron Druid Chronicles). Genuine Celtic myth and folklore is rife with opportunities to use settings, characters, and story elements in original tales of swords and sorcery. In this post, I will provide some writing tips on how to use Celticism in ways beyond the common tropes that have permeated fiction and popular perception for years.

People

A story is nothing without its characters and Celtic folklore, myth, and history is packed with characters that are more than simply roaring barbarians, chimerical yet suave fae, and furtive, tree-hugging druids. Celtic-speaking peoples from ancient into modern times had their own sets of complex customs, philosophies, and societal norms—the same can be said for the characters in their stories. Some Celtic heroes to a degree match the motif of S&S heroes (e.g. Conan, Kull, Fafhrd) who live on the boundaries of society and thus have more connections and encounters with the wilderness and the beings that dwell within—natural and supernatural. These heroes of Gaelic oral folklore and manuscript tradition are known as the Fianna (or Fenians, but that term sometimes carries negative connotations in certain areas of Ireland and the UK) who may have been inspired by semi-nomadic bands of hunters and warriors from the Iron Age made up of aristocratic youths, druids, and rogue satirists. The function of these groups was partially to prepare young nobles in the arts of war, leadership, and survival among a small community.

Heroes of Irish mythology also slant more towards the morally ambiguous attitudes and actions that certain S&S heroes might take, such as Karl Edward Wagner’s Kane and Michael Moorcock’s Elric (or any variation of his Eternal Champion archetype). Cú Chulainn2 for example is unfaithful to his wife Emer several times, uses brutal and unfair tactics against his opponents in battle, and has a literal monstrous side, called the ríastrad (“warp-spasm”), that he uses to lay waste to enemies. Even as a child, he is rather capricious as he injures his foster-brother Conall Cernach to prevent him from claiming the glory from Cú Chulainn’s first expedition to slay men. Fionn mac Cumhaill, a legendary figure in Irish folklore murders his father’s killer, Goll mac Morna, in his sleep despite having him as part of his warband for many years prior. There are even folkloric stories of Fionn and his men killing people in the thousands in order to escape capture from enemies.

The internal affairs and perceptions of heroism within Gaelic culture vary greatly from popular modern perceptions, Christian perceptions, and even other European cultural perceptions. The most common answers to the question, “What is a hero?” usually include “someone who always does the right thing,” “someone who saves people,” and “someone who is good.” What should be taken into consideration when examining the surviving hero-tales of Celtic culture is that many of them may predate Christianity and standardized concepts of good and evil. Heroes, therefore, may do things that we can objectively think of as “good,” but will also be prone to deeds that are overly violent, cruel, or even “evil” to our modern perceptions. Many of their acts performed in the latter category are done to preserve or even enhance their heroic status. One of the most desirable traits of an archetypal Celtic hero is immortal fame that outlives mortal life. Often, Irish heroes die young, but their stories have survived into the modern day as recorded in manuscripts and from oral tradition. Traits such as immortality or invulnerability were not things valued by Insular or Continental Celts, and often they threw themselves into situations that would be glorious whether they died or survived. Bards would then immortalize these deeds in songs that could be spread amongst communities and down generations.

Historically, the cattle raiding martial custom of the Gaels have been labelled as “banditry” by outsider observations from the British. Within the culture, Gaels considered it a greater crime and shame to steal one sheep from a neighbor in secrecy than to lead a full attack upon a rival clan to steal their livestock, which itself was a way to gain heroic recognition amongst peers. The benefit to succeeding at these raids also included an increase of material wealth for both the raiders and their communities.3 The Highland Gaelic clan system was a very different culture relative to other European societies at the time, and also maintained a lot of the ancient philosophies of heroism. Highland warriors prided themselves on being able to overcome significant odds or having the courage to die with honor in a large-scale fight or duel against a rival. The bardic tradition remained strong among the clans and stories about men in their age who could defy death and bring great glory and wealth to their clans through martial exploits were highly valued amongst nobility and commoners alike.

Similarly, S&S heroes may approach “morally grey” philosophies and are also usually entirely mortal and vulnerable, but can embody boundless endurance and fearsome strength. In one of my earliest posts, “Make Your Fights like the ‘Soulsborne’ Games”, I discussed how Conan in “Xuthal of Dusk” emerged from the final fight of the story incredibly bloodied and mangled but still survived. To a Celtic audience, this would be an incredibly glorious deed as Conan seemingly bests death itself. There is also the fact that Robert E. Howard himself was incredibly proud of his Irish heritage and grew up with tales in the oral tradition—which is the favored transmission of Celtic-language folklore—so he might have had some influence from the stories of his ancestors when deciding what could really be “heroic” in his fantasy stories.

The people of the Celtic Otherworld are also often grossly misinterpreted in popular media and perception. White Wolf Publishing’s Changeling: The Lost once rejected a Celtic Studies consultant’s ideas for including more influences from explicitly Celtic stories due to their belief that they had acquired enough from Grimm’s Fairy Tales, which deals with German stories—which are not Celtic in the slightest. Beings from the Otherworld are often labelled as “fae” which is a term that stems from faerie (or fairy, which is etymologically closer to French). Traditional folkloric customs in Celtic-speaking communities have a multitude of names for these supernatural people which include terms like Little People, the Good People, the Boys, and so on. The closest term that might be collectively used would be aes síth (pronounced ahs shee; “People of the Faerie Mounds”). A síth or sidhe in Gaelic folklore and mythology is a faerie mound (sometimes translated as “elf-mound” in older translations), which are places that are often regarded as entryways to the Otherworld or at least sites where supernatural phenomena occur. In Welsh mythology, the idea of faerie mounds is much less overt, but there are still instances of stories where supernatural events occur when characters encounter mysterious hills or mounds. People from the Otherworld can emerge from these mounds or appear in other liminal spaces (such as mist, thresholds of homes, at the edges of society, and in dreams). They are either incredibly beautiful or hideously ugly and for the most part may look human, but can also bear specific traits that range from the colors of clothes they wear (often green, purple, white, red, and black), the types of jewelry or weapons they wield (which can be made of strange materials like gold and silver), or weird physical characteristics like animal limbs, or single eyes with multiple irises. Their personalities and perceptions of the world as well are wholly alien from human emotions (especially in folklore) and philosophies. They are often unapologetically capricious and some of their behaviors border on the decadent, horrific practices like that of the Melnibonéans of the Elric Saga, cannibalism and vivisection included.

One of the possible mythological predecessors of the Otherworldly people in Irish mythology, the Túatha dé dannan (“Tribes of the Goddess Danu”), I believe most definitely can read as ancient sorcerer-kings that ruled over antediluvian worlds of pulp fantasy. Mythology has them studying occult sciences and diabolical arts in either Lochlann (possibly Scandinavia) or the Northern Isles (Orkney, Shetland, and the Faroe Islands). The body of works featuring them the most is the Mythological Cycle4 (but they are sometimes referenced in the other cycles), the most famous story within this cycle being Cath Maige Tuiread (“The Second Battle of Moytura”) where they do battle with the rude, monstrous Fomori (or Fomorians). The manuscript cycle claims they were driven underground by the Milesians (ancestors of the Gaels) and thus became the aes síde. Tales of the Túatha dé dannan are often filled with superheroic deeds, inexplicable magic, and great battles containing larger-than-life heroes and villains. While they might seem like a people more at home in High Fantasy, their stories serve as an epic basis for the pre-history of Ireland.

The Fomori are also interesting mythological figures, subject to as much speculation as the Túatha dé dannan (if not more so), as it is not really certain what they were originally before events such as the conversion to Christianity and the Viking Age changed Ireland entirely. Like the Túatha dé dannan, they also primarily appear in Cath Maige Tuiread and as well in the early text Lebor Gábala Éirinn (“The Book of the Invasions of Ireland”), the latter serving as a list of the numerous peoples who invaded and attempted to settle in Ireland. The Fomori stand apart from the six invading peoples due to the fact that they always seemed to have been in or around Ireland. In Cath Maige Tuiread, there is a reference to them having a home base in Lochlann as well as being from the síde (“elf-mounds”). Cath Maige Tuiread, having been written in the 12th century AD, potentially uses anti-Viking propaganda to characterize the Fomori as sea-faring raiders who illegitimately settle in and tax Ireland. One of their members, Eochaid Bres, has a Fomorian father and a mother from the Túatha dé dannan. He is chosen to rule as king of the Túatha dé dannan in place of Núadu who lost his arm in the First Battle of Moytura when taking Ireland from the Fir Bolg. Bres essentially becomes a puppet for his Fomorian relatives to invade and lay heavy taxes upon the Túatha dé dannan. It becomes so unbearable that Núadu has his arm restored and he retakes the throne. It is likely Cath Maige Tuiread’s authors poured their anxieties about the state of their world, grafting the characteristics of their country’s invaders onto a monstrous race that likely predated the Vikings’ arrival.

This just goes to show how much history itself can influence myth. It is not too dissimilar from S&S worlds like Hyboria where the world contains historical and mythic analogues. It is essentially like how current events can influence popular culture and can even transcend simple analogies by becoming archetypes within genres.

Place

The concept of place in Celtic myth and folklore, and in turn for stories based upon either, is incredibly important. There is an entire genre of poetry in Gaelic storytelling tradition known as dindshenchas (“place-lore”) which are stories that explain the reason behind the name of particular hills, rivers, lakes, mountains, plains, and even simple cairns. Usually these tales involve someone dying in the location and thus giving their name to the place they died or were buried in. I have seen various philistines in historical writings and online discourse mocking how Celtic countries don’t have the same material ruins as Classical and Mediterranean civilizations like Rome or Greece. I believe stories are the real “ruins” of the Celtic landscapes; they contain the literal narratives of the people who occupied certain areas and creates a sort of map that people back in the day could have used to navigate the land based on stories alone.5

Although the Celtic Revival Movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries is often criticized for simplifying the culture and history of Celtic-speaking peoples, poetry and portraits of the landscapes they inhabit are some of the more valuable contributions from the Revival artists. I recently wrote about this in a guest post published on DMR Books’ blog where I discussed James Macpherson's Ossianic poems, a precursor to the Celtic Revival Movement. Essentially, through the use of identifying and extrapolating on the beauty and wonder of the natural world combined with narratives like those presented in place-lore poetry, writers could create an immaterial memorial that acts as a “ruin” to be explored. There might not be any physical remains in the place described (or the place might not even exist), but the audience would be able to explore the story behind the place and the people who lived there and possibly died there.

The Otherworld is also a notable place to use in Celtic-themed stories. Even into the modern day, traditional communities in Celtic-speaking areas hold fast to the belief of a world that exists parallel or even hidden within our own. The Otherworld is normally accessed through liminal spaces that include mist, twilight, thresholds, sleep, and the fringes of society. Visitors in the Otherworld may find normal objects like trees and fruit to be made of strange materials like gold and silver. There might also be bounties of food and beautiful flora and fauna. There are also legends of supernatural islands to the far west where the inhabitants and visitors never age while time outside of their shores marches on as normal. Stories of the Otherworld are often very psychedelic, relying on suspension of disbelief as the very logic of their narratives becomes closer to that of a dream.

Possibilities

Now that I’ve listed out the characters and settings of Celtic myth and folklore, here are some ways writers could implement them into their own works if they're keen on trying to go beyond the normal fantasy stereotypes perpetuated in most popular fiction.

Although gold and other forms of material treasure are coveted in S&S, what truly mattered to many Celtic heroes was the idea of immortal glory; stories of a great and heroic life could outlast even the wealthiest of men. What could make for an interesting Celtic-themed S&S character is one who fights for fame rather than fortune and is willing to leap headfirst into the most dangerous of situations for the sole purpose of having a better story to tell should he survive.

“Celtic Martial Arts” in general is a field of intense speculation especially when factoring in literary references to cleasa (“feats”)6 that are most famously associated with Cú Chulainn’s war-like excellence, but other heroes also have their own repertoire of feats. One of the motifs of S&S heroes is their martial expertise, which often ends up being hulking men wielding huge swords or axes. While this is a perfectly serviceable method of maintaining the ideals of barbarism, intimidation, and raw, primeval strength I have noticed that even the most thrilling combat scenes in S&S don’t make use of flashier, or unique fighting styles or move sets that heroes of myth might have used. Understandably, lengthy descriptions of blow-by-blow fights do not make for engaging prose, but having more unique skill sets and tricks for characters to utilize when they're in a bind could make for fun moments in combat. Bear in mind that the feats we find in sagas have little to no description, perhaps relying on the audience or a storyteller’s interpretation to generate an idea of how a particular feat was executed.

Of course, I could not have an Swords & Sorcery post where I solely talk about the “swords” aspect. Sorcery and supernatural events are plentiful in Celtic myth and folklore. Magic as it occurs in stories doesn't usually have the corrupting effects of eldritch sorceries but it is still often thaumaturgic and can affect direct targets or the world itself through subtle or grand means. For example, magic-users may turn themselves or opponents into animals, the sorcerers of the Túatha were able to bring the sun itself down upon their Fomorian enemies at the Second Battle of Moytura, and music itself could have enchanted qualities to induce laughter, sadness, and sleep in those who listened to it. Folk magic as well has a place among the arcane abilities of the Celts. Folklorist Alexander Carmichael and his descendants and associates compiled the Carmina Gadelica, a collection of Scottish Gaelic folklore in the late 19th and early 20th centuries focusing on hymns, proverbs, and spells. Some of the spells were blessings for good luck, others were blessings that had originally been invoked by saints, and some were curses. Each is relatively simple and short yet in a community where the old ways held strong, they likely could have been wielded to great effect. Sorcerers in Celtic-inspired stories could be unassuming cunning-folk, farmers and old grannies who know a couple tricks to keep foes at bay or how to properly commune with the people of the fairy mounds.

Before I close off, there is also the matter of place. The vistas of the Scottish Highlands, Welsh marches, and rolling southern Irish countryside and bleak coasts are all places that spark the imaginations of fantasy and general fiction authors. The fact many of them remain protected and untouched adds to their primeval majesty, thus making for great backdrops in any story. However, what really matters is of course the story; as mentioned above, how places got their names could be ripe ground for a story by itself, or mayhap characters learning the truth of how a place got its name (see “The Grey God Passes” by Robert E. Howard for inspiration). Places in Celtic folklore also can intersect with the weird, wild Otherworld, presenting a whole new set of adventures or problems for characters. In fact, it is quite common in stories featuring the Otherworld to have its inhabitants seek help from mortal heroes to deal with monsters or otherworldly foes.

The world of Celtic mythology and folklore is one that is shrouded in mists; we are so far separated from it that we can only guess and theorize as to what these stories might have signified during their heydays. As a writer who draws from this mythology, I think that even the fragments alone are inspiration enough to launch hundreds of stories without the need to appropriate or graft other cultures onto them for the sake of “filling it out.” The number of academics in Celtic Studies is a small field, but we are quite passionate and excited to see how creatives can bring new interpretations of these ancient stories and peoples into the popular eye.

Just don’t use Google Translate for Gaelic…

Thanks for reading! If you found some inspiration for your own Celtic-inspired stories, hit the button below to comment what you'll be using!

Keep reading to read a sneak preview of January’s short story: “In the Dragon’s Nemeton.” This is another Eachann MacLeod and Connor Ua Sreng story where the lads, in need of funding for their roving, seek out a treasure hoard rumored to be hidden on the summit of a mountain guarded by an ancient, powerful beast.

The lads waved the dust away from their faces to reveal a large hole running inside the mountain where the boulder once stood. Eachann grinned as he stepped inside the cool, dry tunnel. Connor followed, but turned his gaze skyward as another faint boom sounded—black clouds hovered above the summit. His bones and blood, in tune with the primeval rhythms of the world, sensed an oncoming storm.

“Look, Connor!” cried Eachann.

Connor tore away from the dimming sky and went into the small cave, half-lit by the sun. Eachann knelt before a massive trove of golden furniture, piles of fine silks, weapons and shields encrusted with gems, clay urns painted with scenes of decadence, and jewelry befitting of a king who could rule the world.

“In all my life,” Connor breathed, “never did I dream of a trove such as this!”

Eachann looked back at him, a huge grin and wide eyes taking up most of his fair face. “There’s no way we can carry all of this to Orkneyjar with us, but we know where to find it when we return!” He reached for a broad sword sleeping in a sheathe of ivory and silver.

Before his fingers brushed the treasure, the cave shook as if something slammed into the summit and a peel of thunder blasted the air. Dust rained down from the low ceiling along with chunks of stone and earth. The sunlight streaming into the tunnel dimmed as thick, black clouds blotted it out.

“Macrall!” cussed Eachann, covering his pate. He stood and fled to the exit with Connor.

A warm wind picked up outside, laced with a sharp, metallic scent like heated copper. The lads dashed up the ledge to the summit, halting in place as they beheld the henge, now entirely shattered. The debris spread across the flat space, dust clouds still hanging heavy in the air.

“It looks as if the hammer of the Storm itself smashed those stones.” Connor ground his teeth, lifting his dark brown eyes towards the sky.

“It will destroy us too if we don’t haul what we can out of here.” Eachann turned, moving back to the trove.

Connor remained, still in awe of the destruction covering the summit. The winds picked up, lifting more dust off the ground, grain by grain. The Fer Bolg’s eyes widened as the gusts unearthed masses of shattered human bones. He understood then, the farmers’ tales of the druids placating the beast of Beinn na Beithir.

They did so with gold and blood, he realized.

“Eachann!” he shouted, running after the Gael. “We must—”

A roar of thunder tore across the summit, shaking Connor down to his very bones. His gaze too went watery at the sheer might of the blast and he shut his lids to clear his eyes. Once he opened them, a huge, serpentine shape descended from the clouds over the southern side of the mountain.

“In the Dragon’s Nemeton” will be available to read in full on Friday January 26th! Share this post with the button below to spread the lore!

Senchas Claideb is still looking for some more authors for our Contemporary S&S Author Sound-Off post at the end of January! This final post will be essentially a chance for authors currently in the scene to share some of the stories they are working on and spread their lore onto Substack! If you would like to participate or know someone who would, follow this link to fill out a short survey and you’ll be included in the sound-off!

Follow me on other platforms linked below!

The term “Celtic” can be most accurately applied to an Indo-European language family that encompasses the Goidelic and Brythonic language groups, the only Celtic language groups that are spoken today. The surviving Celtic languages include Breton, Cornish, Irish, Scottish Gaelic, Manx, and Welsh.

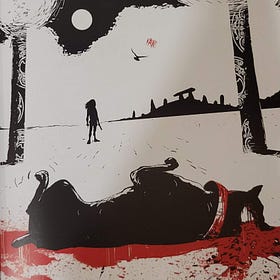

Cú Chulainn is one of the foremost heroes of Irish saga literature. His story was subject to a graphic novel adaptation by Paul J. Bolger titled Hound, which I am in the process of reviewing in multiple installments where I compare the mythological Cú Chulainn to his dark fantasy counterpart. To read my reviews released so far, follow the links below:

"Hound" - First Impressions

This is far from the formalized review I have planned for the Hound graphic novel, but I wanted to give my readers a preview of my initial thoughts after finishing it two weeks ago. Hound captured my interest when I came across its Kickstarter page back when I was in college (either in 2019 or 2020). I had not taken a formal class in Irish mythology or C…

"Hound" Review

(Credit: Paul J. Bolger, 2022) As mentioned in my “First Impressions” post I had been casually following Paul J. Bolger’s Hound since 2019, before I started my master’s in Celtic Studies but after I read several versions of Cú Chulainn’s stories, the

"Hound" The Scholarly Review I - The Conception and Boyhood Deeds of Cú Chulainn

I mentioned in my general review of “Hound” that I might have to split my scholarly review into separate parts. I decided it would be best to do that based on the primary “episodes” that make up the life and saga of Cú Chulainn. This review will be examining Paul J. Bolger’s

Cattle and other livestock remained a standard form of currency among Scottish Highland Gaels even in the years leading up to the Battle of Culloden Moor in 1746. The Battle of Culloden Moor was the final battle of the 1745 Jacobite Uprising fought between the Jacobites and Hanoverians in Scotland. This engagement is largely considered to mark the decline of Highland Gaelic culture in Scotland as many Gaels supported the Stuart Dynasty which was supported primarily by the Jacobite faction.

Medieval Irish Manuscript Tradition is divided into four “cycles” (or categories): Mythological, Ulster, Kings/Historical, and Fenian. The Mythological Cycle largely deals with pre-historic events and supernatural characters, such as the Túatha dé dannan.

In one of my earliest posts, I discussed the idea of ditching maps in fantasy stories in favor of focusing the narrative on the primary characters, utilizing elements such as place-lore to build the world around them as they explore it. Read it at the link below:

A Case for Losing the Maps

A worldbuilding practice many fantasy writers (especially new ones) utilize is drawing a map of their secondary world. If they publish their novel or collection, they might include it on one of the first pages or inside the cover. These maps broadly indicate the major nations and biomes we might see in the story or series. Some elaborate maps may also h…

The most extensive list of feats is references Cú Chulainn's martial training:

[T]he apple feat - juggling nine apples with never more than one in his palm; the thunder-feat; the feats of the sword-edge and sloped shield; the feats of the javelin and the rope; the body-feat; the feat of Cat and the heroic salmon-leap; the pole-throw and the leap over a poisoned stroke; the noble chariot-fighter's crouch; the gae bolga; the spurt of speed; the feat of the chariot-wheel thrown on high and the feat of the shield-rim; the breath-feat, with gold apples blown up into the air; the snapping mouth and the hero's scream; the stroke of precision; the stunning-shot and the cry-stroke; stepping on a lance in flight and straightening erect on its point; the sickle chariot; and the trussing of a warrior on the points of spears.

In Foglaim Con Culainn (“The Training of Cú Chulainn) in addition to Cú Chulainn’s feats, the sons of his mentor Scathach also have their own unique feats named after them, which unfortunately lack precise description of their function.

A very interesting post! One thing I find intriguing is that when one thinks of “Celtic”, they automatically think of the British Isles, yet there were Celtic tribes on the European continent as well stretching from France, Hispania, all the way to Central Europe. Why aren’t there any Celtic stories set in continental Europe?

I've also found that on closer inspection, mythology really is treated poorly (and even disrespected) by a lot of current fiction and fiction authors that use it, so I've become a lot more careful about my own research. And it has made me enjoy some works a lot less, I stopped playing one game after digging into actual mythology made me realize more of its depictions were awful than good.

At least with my secondary world fantasy I loathe the idea of a direct real world counterpart, so even unintentional distinctions from what I use as inspiration can work in my favor, while writing about mythology directly is obviously much more strict on faithfulness. One major misconception people seem to have is that they think the absence of a canon means its impossible to be wrong, when there is a difference between the natural evolution of culture and a comic book writer making something up.

I'm only a hobbyist in terms of research, but google scholar, JSTOR, and looking for proper academic books/PDFs has done a lot to help me move past the basic wikipedia info and get to the real meat of things. Though my own efforts have been mainly focused on the Aztec, the god Tezcatlipoca in particular, whose treatment in/by pop culture I despise and would argue still has traces of colonial attitudes.

Also I had just finished reading The Saga of Hrólf Kraki and His Champions before reading this, so while not Celtic I thought of it when you mentioned the importance of fame for warriors. I think ultimately there needs to be more of an effort from people to understand mythology on its own terms, not conform it to our own.