The Melancholic Longing of the Second Poem in "Fragments of Ancient Poetry"

A Counterfeit but Beautiful Scene sung by the Blind Bard

James Macpherson is a controversial figure in Celtic and Scottish Studies due to his influence on 18th century romantic literature and establishing motifs that would become commonplace in the Celtic Twilight movement of the 19th and 20th centuries. His seminal works of Ossianic poetry were meant to give Scotland a national and artistic identity following the debilitation of Highland Gaelic culture in the wake of the final and failed Jacobite Rebellion of 1745-6. Folklorists, historians, and tradition-bearers, however, are rather disgruntled by the warped perceptions Macpherson created of traditional Gaelic folkloric heroes and events.1 The poems gained widespread popularity in Europe with Napoleon himself even owning a copy of the poems that he was said to have carried into battle, and Wolfgang von Goethe (author of the play Faust) devising his own imperfect translation to spread throughout Germany. They are effectively a highly fictionalized version of the Irish Fenian Cycle, dealing with versions of Fionn mac Cumhaill, his family, and friends. At the center of them all is Ossian, a blind bard who is the last of his people, lamenting them in the empty wilderness of Caledonia.

Critics of Macpherson even often dismiss the poems themselves, calling them turgid or overwrought. At best, academics at least acknowledge the artistic value of these poems while separating as having any actual weight concerning the storytelling traditions of Gaelic-speaking communities. Personally, although I strive for accuracy and academic integrity, I fall more in line with the latter class of critics, I may at times, however, be an unapologetic Macpherson fan since I also remember the context in which these poems were written—as sort of a reaction to Highland Gaelic culture being beaten down by imperialist forces and Macpherson, a native Gael, growing up in a world where being Gaelic was taboo. His poems reflect that very feeling at a time in history where the future of an entire language and culture looked incredibly bleak. Even if his poems are not to be taken as true cultural artifacts of Gaelic storytellers, they at least provide insight on the anxieties and sorrows of extinction.

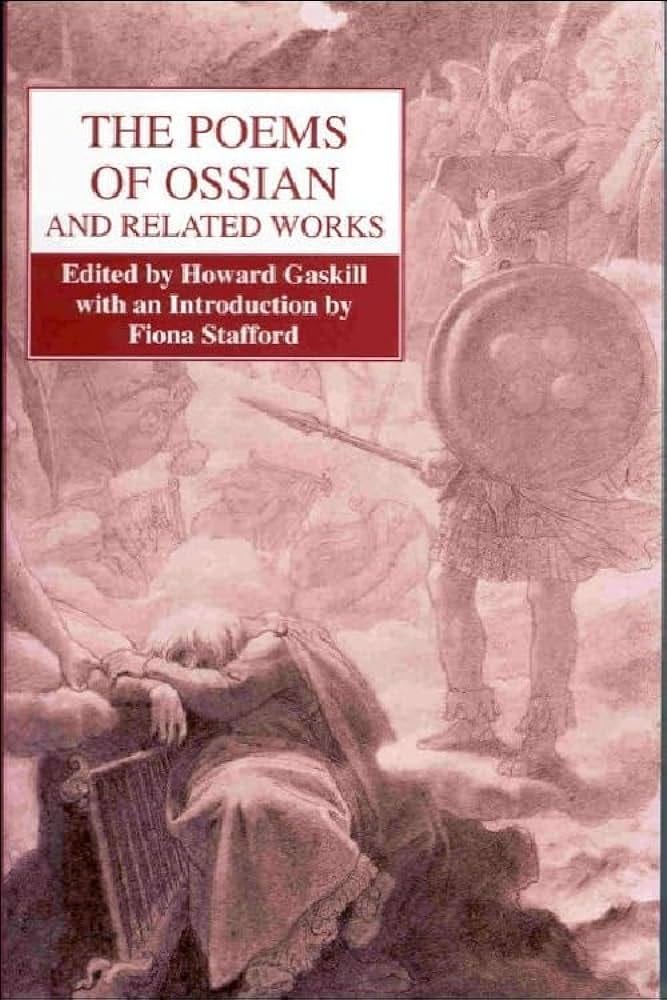

In my sophomore year of college, I took an intermediate poetry course as per my requirements for fulfilling my creative writing major. The course itself irreparably damaged my urge to write poetry on a whim, but it at least exposed me to different forms of poetry and led me to getting my hands on what would become one of the most influential texts in my writing career. I forget the exact reason why I was prompted to seek out a book of poetry of my choice for class, or if I just happened to recall the name “Ossian” mentioned by my main lesson teacher for my “History through Music” class in 11th grade and wanted to explore it for myself. Whatever the case, I purchased a copy of The Poems of Ossian edited by Howard Gaskill and started reading it that night. What struck me was the almost postmodern formatting of the first collection of poems in the book (Fragments of Ancient Poetry, originally published in 1761), which sets them up as somewhat imperfect and in ways that demonstrate obvious editorial intervention—from Macpherson more than Gaskill. It was not until my senior year of college that I read Corinna Laughlin’s article “The Lawless Language of Macpherson’s Ossian” where I found a quote that has stuck with me for years afterward: “Macpherson makes us feel…we are reading an epic in ruins.”2

This rings true in terms of how the poems are presented and the contents of them; they are simultaneously epic and tragic, taking place at the twilight of a nation. Keep that in mind as you read the second poem from Fragments:

I sit by the mossy fountain; on the top of the hill of winds. One tree is rustling above me. Dark waves roll over the heath. The lake is troubled below. The deer descend from the hill. No hunter at a distance is seen; no whistling cow-herd is nigh. It is mid-day: but all is silent. Sad are my thoughts alone. Didst thou but appear, O my love, a wanderer on the heath! thy hair floating on the wind behind thee; thy bosom heaving on the sight; thine eyes full of tears for thy friends, whom the mist of the hill had concealed! Thee I would comfort, my love, and bring thee to thy father’s house.

But is it she that there appears, like a beam of light on the heath? bright as the moon in autumn, as the sun in a summer-storm, comest thou lovely maid over rocks, over mountains to me?—She speaks: but how weak her voice! like the breeze in the reeds of the pool. Hark!

Returnest thou safe from the war? Where are thy friends, my love? I heard of thy death on the hill; I heard and mourned thee, Shilric!

Yes, my fair, I return; but I alone of my race. Thou shalt see them no more; their graves I raised on the plain. But why art thou on the desert hill? why on the heath, alone?

Alone I am, O Shilric! alone in the winter-house. With grief for thee I expired. Shilric, I am pale in the tomb.

She fleets, she sails away; as grey mist before the wind!—and, wilt thou not stay, my love? Stay and behold my tears? fair thou appearest, my love! fair thou wast, when alive!

By the mossy fountain I will sit; on the top of the hill of winds. When mid-day is silent around, converse, O my love, with me! come on the wings of the gale! on the blast of the mountain, come! Let me hear thy voice, as thou passest, when mid-day is silent around.3

In the moment, I thoroughly appreciated reading this poem and others in the collection, but my actual analysis of it—when I actually took the time to sit down and absorb the poems—came as I wrote my critical component to my senior capstone project. My research focused on the Celtic Twilight and fantasy media influenced by the movement; I drew a lot of information from Macpherson’s Ossianic works as a result and emphasized the idea of liminality and longing. Fragments perfectly embodies the feelings of the uncertain period Macpherson grew up in following the suppression of Gaelic language and culture. In my capstone, I postulated that the narrators in Fragments of Ancient Poetry are representative of a “middle period” or people living on the interstice where the past is slowly slipping away and the future is uncertain or even nonexistent. The symbolism of twilight is highly apt for this type of poetry as dusk and dawn can be applicable to the situation the Ossianic characters and Macpherson find themselves in—dusk representing the past and the sun having set on it and dawn representing the possibilities of the future. A character who represents the concepts of dawn is Ossian’s son Oscur, a promising warrior and grandson of Fingal (Macpherson’s version of Fionn mac Cumhaill). Oscur, however, never gets to live up to his full potential as the legacy of his people (his death is described in the sixth poem in Fragments), thus the gloomy finality of dusk may also apply to his character.

Reading Macpherson exposed me to a new lexicon of words, styles of writing epic stories that can make them truly feel out of another time, and scholarly research into how people may mourn the loss of heritage through art. Although I actively avoid trying to be as verbose and purply as Macpherson in my normal fiction, I take heavily from his descriptions of the natural world and emotion in order to add a flare that makes its pre-Celtic-Twilight influences known. It is one of the texts that came into my life which I feel a very personal connection with. It's something I could read over and over like how some readers have a classic novel or poem they can return to time after time. Macpherson's Ossianic poetry embodies how I viewed Scotland and Gaelic culture when I was younger, before I learnt of the nuances and actual history of the place and people. Now, I can read it and still appreciate the effort that Macpherson put into this work while also acknowledging the existence of authentic Gaelic tradition-bearers who have been able to keep what few memories we have of the language and culture alive into the modern day. Even in academia I have seldom found someone who shares my enjoyment of Macpherson, so I normally keep this influence in a very special place in my collection and sources of inspiration.

Thanks for reading this week’s post! Are there any poems or poets that opened your eyes to new ways of writing? Leave them in the comments using the button below!

Refer a friend to Senchas Claideb and receive access to special prizes, including a personalized Gaelic phrase and a free, original short story!

Follow me on other social media platforms!

“The Ossianic Controversy” caused by Macpherson’s “discovery” of ancient manuscripts and poems that he claimed to have strung together in a narrative that gave proof of Scotland’s artistic and national value in the face of English imperialism. Macpherson, however, made up most of his sources or failed to cite them entirely—although he did make an expedition to the western Highlands and islands to gather information on stories that inspired his works.

Corinna Laughlin. "The Lawless Language of Macpherson's Ossian." Studies in English Literature, 40.3 (2000): 512. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1556259.

James Macpherson. Fragments of Ancient Poetry in The Poems of Ossian edited by Howard Gaskill (Edinburgh University Press, 1996): 9.

MacPherson sounds like a fascinating figure, even if many scholars doubt the veracity of his claims of coming across Ossianic poetry and translating it from the original Gaelic. He was undoubtably a very talented author. I can understand why people would be upset by his dishonesty, but it sounds like he cared a lot about Celtic culture, and around the time he was writing., there was very little scholarship on the subject, so I can at least laud him for trying to spread awareness of it.

Your deep-dives of Celtic history and literature and always so fascinating!

Years ago John Dolan aka The War Nerd shared a fascinating paper from his time in academia where he compared James Macpherson to both John Smith (of the Mormons) and literary forger Thomas Chatterton. I believe he argued that Smith and MacPherson were closer to each other than either was to Chatterton. I can't find the actual paper in my files right now, but I did come across this note I must've made at the time: "Also a really interesting discussion about the ways people actively suspend their disbelief, and the needs of the Americans and the Scots to find a better history for themselves (Dolan argues the English were secure enough not to need this, and thus Chatterton was the only failure among these three examples)."