"The Brave and the Bold" - The Scholarly Review III

A Celtic Studies Scholar reviews Batman and Wonder Woman's caper in the Celtic Otherworld

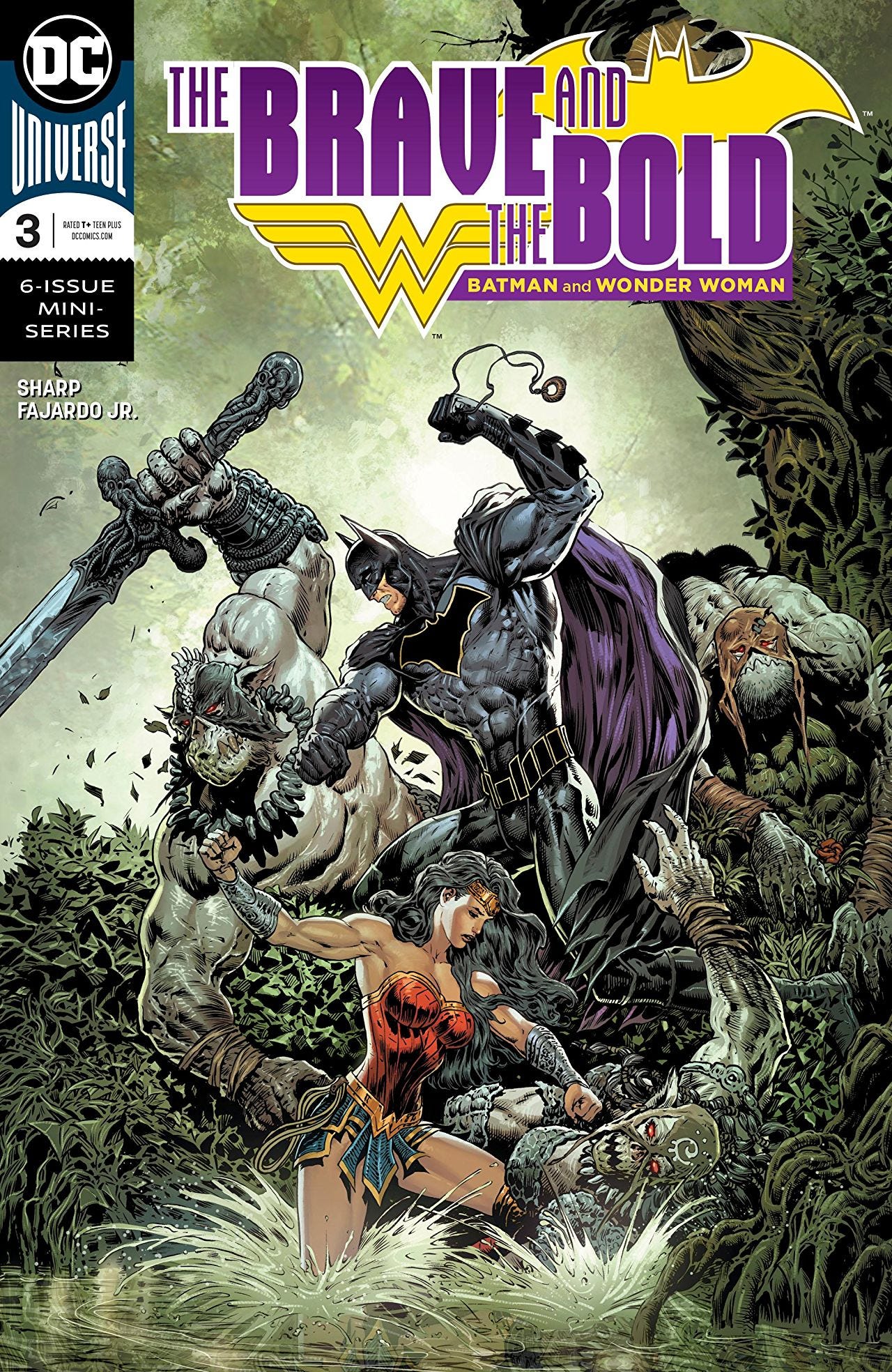

There is something rotten in the world of Tír Na nÓg and the World’s Greatest Detective is finally on the case! Wonder Woman brings Batman into the Celtic Otherworld to solve the alleged murder of a god. Although the magic of this supernatural land confounds Bruce Wayne’s scientific mind, he soon learns there may be more going on than what can be seen on the surface.

Catch up on the other parts of the review!

Bridging the second and the third chapter, Wonder Woman visits Batman with the help of Cernunnous in order to recruit him to solve the alleged murder of the Fomorian King Elatha. Although he is willing to lend his aid to the Otherworld, Batman is hesitant about staying for long due to the waking nightmares plaguing Gotham’s Irish Quarter. Wonder Woman reinforces the fact that “time flows differently” in Tír Na nÓg. Again, this falls in line with how many Otherworld stories portray journeys wherein time will pass differently within the Otherworld as opposed to the mortal world. In the case of The Brave and the Bold, time seems to pass more quickly within Tír Na nÓg than on Earth, making it more convenient for the purposes of Batman’s mission in Gotham. Soon after Batman’s arrival, he goes out with Wonder Woman across the Otherworld to obverse the land itself and the goings-on, all the while attempting to apply science to every minute detail.

One of the most striking points of The Brave and the Bold’s third chapter is Batman’s relationship with Irish folklore. On his ride with Wonder Woman, he explains that he had an Irish nanny named Dora from County Cork who spun him “fabulous tales of Oisin’s wide wanderings and of the little girl stolen away from Coloney Village for seven years by the ‘gentry’…” Since superhero backstories can be subject to incredible change based on storylines and authors, I did not bother trying to verify if any other comics that touched on Batman’s youth made any sort of reference to or showed an Irish nanny. For the purposes of this particular story, I suppose it is a convenient detail to help “hook” Batman into going along with the weirdness of the Celtic Otherworld.

He precedes his mention about his nanny by confessing he know only a little bit about the lore, but decides that it is the only way to help supplement his scientific analyses. The choices of stories he mentions are definitely things that most tradition-bearers in Irish communities would know very well; they slant more towards the heroic and supernatural genres of stories respectively, but most folk storytellers from Ireland likely would have at least a few tales about the Fianna and faeries in their repertoire. Furthermore, both Oisín and the “gentry” have connections with Tír Na nÓg itself, which makes sense as to why the Sharp chose these for Batman to reference specifically; Oisín, son of Fionn Mac Cumhaill, famously leaves the Fianna after being coaxed by the otherworldly woman Niamh to Tír Na nÓg, only to return to Ireland by the time St. Patrick’s conversion has already gone underway; the more personal story about the little girl stolen by the gentry is similar to regular accounts of Faeries kidnapping people in rural Irish communities.

Batman’s convenient link to Irish folklore comes in handy later on in the story, but for the time being it’s a simple addition to help give him something to work with as if solving the mystery of a god’s death wasn’t incentive enough.

Another interesting part of this chapter is that we get a better look at what the comic seems to portray common Fomorians as. In my previous reviews, I made mention that the Fomorians mostly seem to have orcish traits (i.e., grey-green skin, pointed ears, tusks or fangs, etc.), but at the same time there are members of their tribe who appear more human-like or at least closer to the fair, tall, elfin Dé Danann—such as Elatha and his wife Ethné (who mostly appears in the background until the next chapter). Batman and Wonder Woman encounter three Fomorians who appear in the manner of the common, orcish variation of their race. They are also invisible, but are discovered by Batman when he chances upon and uses a hag stone,1 a small stone with a hole naturally eroded into it. I suppose these Fomorian characters were meant to provide a bit of comic relief as suggested by their names—Maggie, Declan, and Lug. The first two names are obviously modern Irish names that are common but might border on the line of stereotypical, and the last (at first glance to a Celticist) looks like the same name as the mythic King Lug of the Tuatha dé danann, but was more likely to reference this Fomorian character being big and oafish (i.e., being a “big lug”) rather than having any relation to the mythic character—whom ironically has Fomorian heritage.

The odd choice of names aside, these Fomorian characters provide a bit of interesting exposition about their people and the current situation in Tír Na nÓg. They reinforce that they are part of the sidhe (or are the people of the sidhe, which are the fairy mounds in Gaelic folklore), which makes them linked to the Dé Danann even if they struggle to coexist. I touched on this point in the first part of the review, but to summarize, Cath Maige Tuiread implies that the Tuatha dé danann and Fomori have a shared heritage or at least possess similar qualities as supernatural people—the text at one point even calls them the “warriors of the síd.” Another interesting point is that they seem to behind a series of raids that happened off-screen in the time leading up to the story. This is sort of a regular portrayal of Fomorians in pop culture as barbaric or simply monsters (their character designs tell as much). The ones speaking to Batman and Wonder Woman, however, imply they know a little more about the mystery behind Elatha’s death than they may be letting on. Maggie simply states, “The King wanted change” after explaining her King’s regrets of the stagnation and “malaise” plaguing the people of Tír Na nÓg

One of the most interesting aspects of this chapter is the further characterization of Tír Na nÓg as a place as well as its inhabitants. In one of Batman’s initial hypotheses about the Otherworld’s existence, he describes it in a manner that implies he thinks of it as a sort of simulation, questioning if the sun is even real. Near the end of the chapter, Batman and Wonder Woman reach the tangible border of Tír Na nÓg, the “dread ring,” so-called by the narration text, which rises from the sea up to the clouds. Wonder Woman immediately contrasts this to her otherworldly homeland, Themyscira, which has no border—this is another detail on the wider lore of DC comics that folks are free to help verify and explain in the comments. When discussing the “spirit world” in folklore, mythology, or in general, often times we might imagine there being a border between “this world” and “the next.” In most myths, otherworldly locations like Olympus, Aesgard, Helheim, and Hades were considered to be actual places people would physically travel to, so long as they met certain conditions or knew how to locate it. In Irish folklore and literature, the otherworld can be a bit more obscure in the sense of where it was located, but usually it could be accessed also under certain conditions ranging from location to time of day or even relativity to society.

On a less concrete topic, Batman also makes an observation about the uneasy existence the people of Tír Na nÓg lead with constant fighting and feuding while they are trapped in this prison they made for themselves. He describes their conflicts as “games,” which have no real consequences or progression. On the one hand, it brings to mind the idea that otherworldly entities likely have a different view on violence and warfare than earthly humans; many stories portray creatures like elves regarding death and war as being of no real consequence or even something to look forward to. It is also telling about the stagnation the people of the sidhe face while confined to the Otherworld, but to me it also read as possible commentary on the nature of myths and folktales concerning the supernatural or heroic characters from tradition. Storytellers from Gaelic tradition generally don’t strive to innovate or create new stories, their main function as members of their community is to remember and recite certain stories so new generations might remember and recite them in turn. It is certainly possible for tradition-bearers or other members of traditional communities to tell stories, gossip, or legends as they happen in and around their home, but certain cycles of stories often remain mostly unaltered with a deep reverence for the material, namely stories of the Fianna. (I could go on about different literary theories concerning the Fianna and Fionn Mac Cumhaill, but I’ll keep it brief here.) Although the end of the Fenian Cycle is something that is acknowledged in folk and manuscript tradition, the stories are still told over and over again. The characters are, in a sense, confined to their cycle of stories seemingly without end or alteration to who they are as people.

It was moments like this where it really did seem Sharp had let his research or storytelling abilities shine through. It certainly made me want to read on and see what happened next!

Thanks for reading this week’s post! Share this with any friends or family that are fans of Batman or DC Comics as a whole!

Refer your friends to Senchas Claideb to receive access to special rewards, including a personalized Gaelic phrase and a free, original short story exclusive to top referees!

Shoot me a message!

If you like what I do, consider leaving a tip!

I don’t know enough about folk magic from primary sources to comment thoroughly on reports about hag stones, or “adder stones” as most sources online seem to lump them under, but it seems like there are various terms, uses, and stories surrounding these objects from the British Isles to Scandinavia. Generally they seem to be stones that have holes or knot-like formations caused by erosions, but traditional explanations claim them to be formed by a serpent’s spit or venom (thus the term “adder stones”). The Wikipedia entry (normally I don’t use Wikipedia for serious research, but if a page is cited correctly it can be an adequate method of finding secondary sources and a few primary sources) also listed Gloine nan Druidh (lit. “The Glass of the Druids”) as a Scottish Gaelic term for this. Wanting to verify it since the English page on the subject did not list where this term came from, I found the Scots Wikipedia page on “Edder stanes” (Scots being the Scots Leid, the language spoken in Lowland Scotland that is one of the closest-sounding languages to Middle English; while it is a Germanic, not a Celtic language, it has some words that borrow from Scottish Gaelic) where it provided a few more sources. (Incredibly, I can read some Scots Leid simply from exposure to the poetry of Robert Burns and Scottish folk music.) Some of the sources, which I will definitely be adding to my bookmarks, include The Scottish Gallovidian Dictionary by Sir John Mactaggart and An etymological dictionary of the Scottish language by John Jamieson (although the latter didn’t seem to have any reference to “edder stanes” or Gloine nan Druidh upon my initial glance). Most helpful, however, was referencing volume 1 of Edward Dwelly’s Illustrated Gaelic Dictionary (p. 505), which included a subentry on Gloine nan Druidh that quoted Pliny the Elder’s observation on druidic rites and reverence for these types of stones—the Scots Wikipedia page on edder stanes also included this quote. In terms of any supernatural properties they might have, I also also can’t say for certain what they can do in traditional folk beliefs, but it could be possible for them to help reveal hidden creatures or objects as a lot of real-world magic tends to involve sight or looking at things in certain ways.