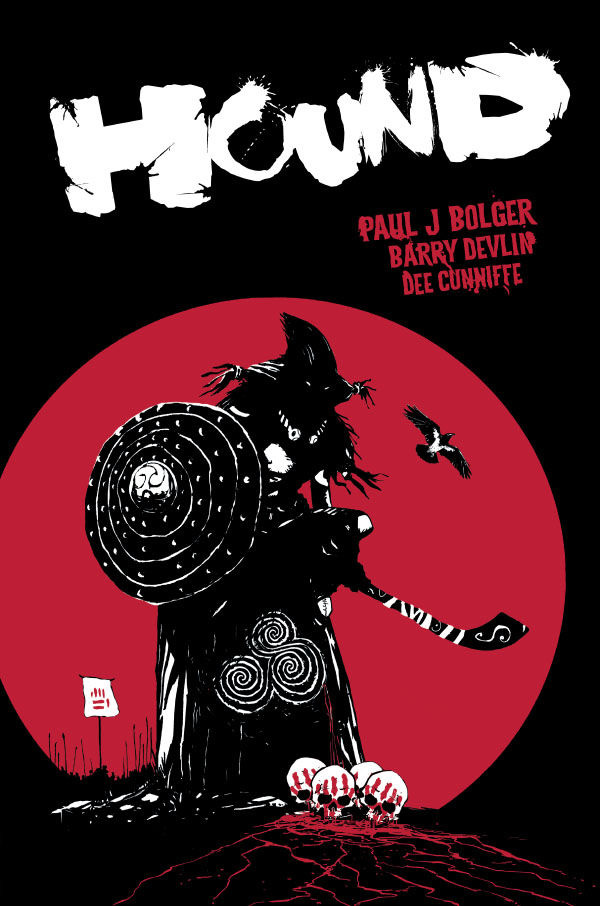

"Hound" Review

My general review of Paul J. Bolger's epic graphic novel adaptation of Irish myth

(Credit: Paul J. Bolger, 2022)

As mentioned in my “First Impressions” post I had been casually following Paul J. Bolger’s Hound since 2019, before I started my master’s in Celtic Studies but after I read several versions of Cú Chulainn’s stories, the Táin Bó Cúailnge, and several other tales from the Ulster Cycle.1 It came back on my radar when I started gearing up to run Senchas Claideb; I decided that part of my posts would include reviews of Celtic-inspired media and Hound would be the perfect subject for a first review.

Hound will be receiving two separate reviews (the second might have multiple parts to it). This review is primarily examining Hound as its own piece of modern media, without much reference to the mythic source material. I will be acknowledging here that it was inspired by the stories of Cú Chulainn, but this will mostly be a “taken face value” review.

There will be minor spoilers here, but if you would like to read Hound first before continuing, follow this link to Darkhorse Comics’ store to get your copy and support the author.

Story

Hound takes place in Ireland ca. 50 BC, which is emphasized as one of the only places in the known world that has not been conquered by Rome. The prologue of the story is narrated by the Irish goddess the Morrígan, one of the Túatha dé dannan (called “the Followers of the Great Mother Danú”; allegedly the pantheon of pre-Christian Ireland). At the end, she reveals her people “forgot how to fight” and fell to the “Sons of Mil…from Galicia [northern Spain]…” finding refuge in subterranean mounds throughout Ireland. Morrígan calls herself “the last of [her] kind” and concludes to prologue by revealing that she is dying.

The focus of the story is on the warrior Cú Cullan,2 claimed to be the child of the Irish “Sun God” and the sister of King Connor of Ulla (the northern Irish province Ulster). The Morrígan takes a special interest in him, kidnapping him from his cradle and imbuing dark powers of war and slaughter within him. She indicates that Ireland is in a period of relative peace and, being a war goddess, she intends to use him as her “Dark Blade” to cause and stir up violence throughout the Isle.

The entire “youth and training” period of Cú Cullan’s story (from the time he is 13 up to 26) deals with the young warrior battling against the seeds of frenzy planted in him by the Morrígan, and struggling to find a purpose in King Connor’s retinue, despite the praise mounted on him as the “Protector Hound” of the province. He finds friendship, love, and prospects of a peaceful life throughout this period, all contrasted by the endemic violence plaguing his mind. He also acquires superior skills in martial arts, which seems to allow him to find control over his battle-lust—but also prepares him to be the “Dark Blade” the Morrígan wishes him to be.

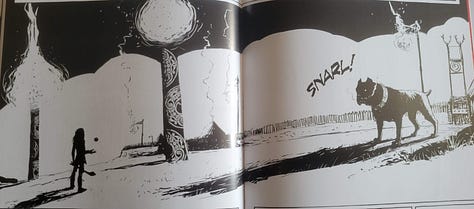

This segment of the story is dripping with dark fantasy edge and relishes in its mythic and prehistoric inspirations. Despite the dour atmosphere, character designs, and themes there is at least a sense of honest fun in the beginning parts of Hound which I find is reflective of most beginnings of mythological stories; the grimmer stuff usually comes later, even if the start has tragedy and troubling episodes.

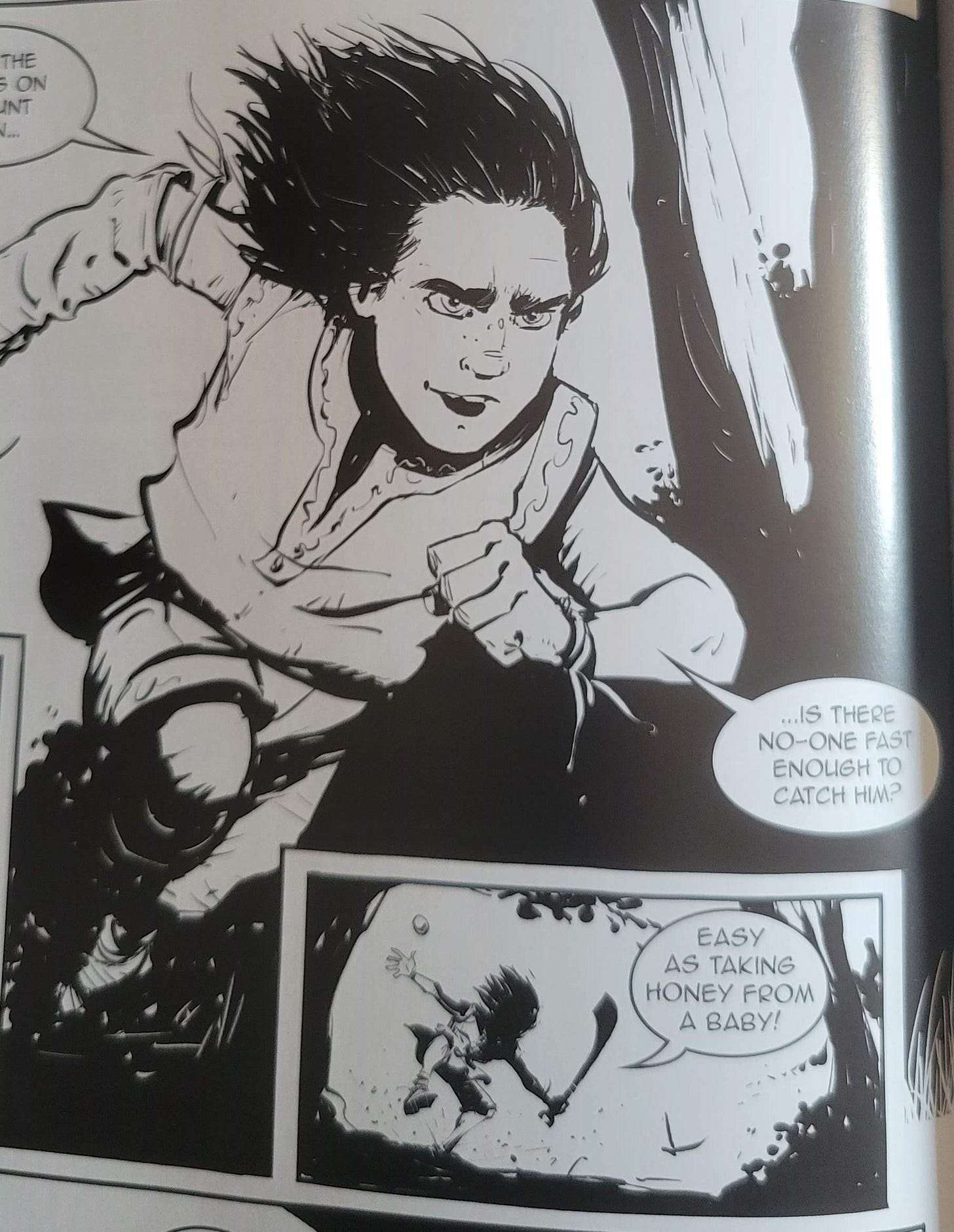

(Above: Young Cú Cullan running in search of a fight)

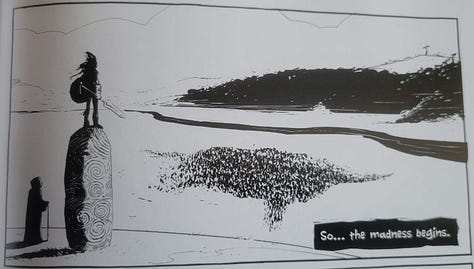

Most of the latter half of Hound focuses on a conflict between Ulla and the western province Connact, ruled by Queen Maeve and her consort Prince Alil. Jealous of Alil’s wealth, Maeve sends thieves to steal a prized brown bull owned by the farmer Ferrell. The theft of the bull is botched, provoking Cú Cullan to take up arms against the invading Connact army as Ulla’s sole protector. This section (even barring my scholarly opinions) feels rather rushed and blends a bit roughly into the third act. Something I notice about comics is that they have a habit of skimming over or omitting information or supplementary panels, and those plot holes shone especially bright in this part of the story. It does, however, contain one of the best and emotionally charged fight scenes in Hound, which remains true to the source material.

The final act of Hound unfortunately fell a little flat for me and I had a hard time segregating my judgement of it as its own piece of media from an adaptation of complex, mythic source material. Reading it, I felt as though Bolger attempted to remain true to telling his own version of Cú Chulainn’s saga This part also contains another emotional fight which, while not as strong as the aforementioned one, contains striking imagery and brief, yet poignant moments. It also has a very interesting rendition of the famous “warp-spasm” that I’ll further explain in my scholarly review of the graphic novel.

Overall the story has a very strong start that remains true throughout most of the middle. The latter half, however, begins to peter off as we are treated to a parade of references crammed into a somewhat rushed ending. The very conclusion of Hound does offer some stellar imagery and leaves readers with a firm anti-war message that is endemic to many modern Irish stories and songs—and has potential roots in the overall message of Hound’s source material.

Characters

The story devotes most of its time to the relationship between Cú Cullan and the Morrígan, but hosts quite a large cast of characters.

Cú Cullan seems conflicted with his desire to be a warrior, especially in his later years; he begins as a youth who is eager to prove himself as the greatest warrior of Ireland, despite the taunts of his peers. He struggles with his violent nature after gaining some renown in his early adulthood, actively shunning some violent mannerisms of his fellow Ulstermen. Even in his latter years, when he tries to divorce himself from his violent nature and warlike expertise, Cú Cullan retains his dignity as a man and protector of his people and province.

The Morrígan serves as Hound’s antagonist; as the goddess of war she puppeteers conflicts and exacerbates Cú Cullan’s bloodlust so he may kill in her name. The reasoning behind her meddling with Cú Cullan and the affairs of mortals is that she wishes to break an inexplicable “peace” that has fallen over Ireland. Barring even scholarly notes, it is a bit dubious to imagine a period of human history anywhere where conflict of some kind was nonexistent. Her orchestration of the raid led by Connact, however, did feel more organic than her direct warping of Cú Cullan’s mind. It’s difficult to see why the Morrígan chooses Cú Cullan as her champion other than the fact he might have godly lineage, which is hinted at in the beginning and towards the end. Since the nature of the old gods in Hound are kept mostly quiet (which is reasonable given that we know very little about the pre-Christian Irish deities) we can’t say for certain if it’s because of Cú Cullan’s alleged parentage or if simply the relationship between him and the Morrígan was emphasized for the sake of this adaptation.

The supporting cast I will examine closer in my scholarly reviews, but for now I will say that most of their purposes revolve around Cú Cullan rather than standing out as their own person with goals, dreams, and a firm role in the story. I will mention that the side character who stands out the most is Cú Cullan’s best friend Ferdia, a Fer Bolg warrior from Connact. I have a lot to say about Ferdia, which I will save for my scholarly review, but I am very glad Bolger kept this integral emotional relationship from the source material. Some of the best interpersonal moments come from Cú Cullan and Ferdia’s interactions, bringing joy and sometimes comic relief to an otherwise grim world.

Art

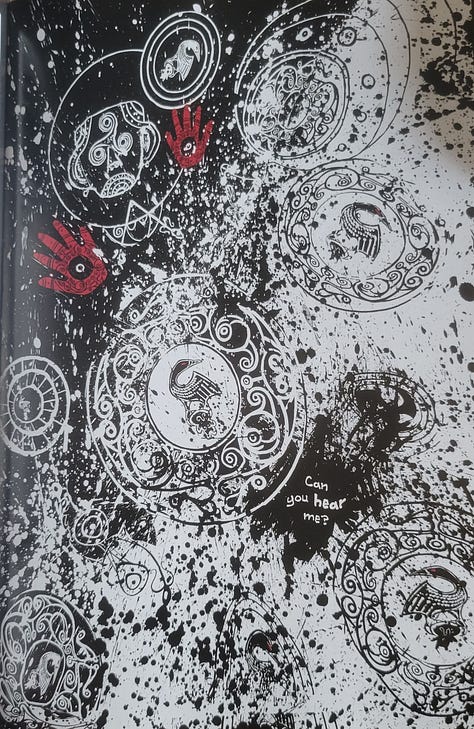

What really stood out to me about Hound’s artwork, as I mentioned in my “First Impressions,” was the similarities to the illustrations in Kinsella’s edition of The Táin. Hound and The Táin’s illustrations have stark, graphic linework and evoke a primitive mood that captures the period the story is meant to take place in—a prehistoric Ireland. It wonderfully compliments the violent, harsh nature of Cú Chulainn’s story but also does not lose the mystical, “Celtic” qualities that are popular in visual interpretations of all things “Celtic.” What makes it stand out from standard Celtic media is Bolger’s references to actual Iron Age technology and clothing, as well as the prehistoric symbols and standing stones that found in the old tombs of the Isle. Viewing these, I was struck and inspired in a similar way as when I had first visited Ireland years ago and almost felt as if I had been returned to the Isle itself by immersing myself in the pages of Hound. Despite the color palette being limited to black, white, and red I could easily see the greys, greens, blues, and golden sunbeams that also swim in the natural Irish landscape. This is also true of the costumes, artefacts, and manmade structures; Bolger put in a great amount of research to show us a time in Ireland—or time period in general—we don’t often see portrayed in media—the Iron Age. Hound’s visual fidelity to the period it portrays (aside from its interpretation of the Gae Bolg) is phenomenal and easily one of the high points of the graphic novel. Any reader, casual or scholarly, will have to admit that every scene in Hound brings to life a time and a place we have barely seen done before.

(Credit: Paul J. Bolger, 2022)

Tomm Moore, who wrote the foreword in Hound, wrote and directed the animated films The Secret of Kells and Song of the Sea, both of which also draw inspiration from medieval and earlier Irish artistic sources. They are direct contrasts to Hound, being aimed at a rather young demographic, but nonetheless carry the same spirit of breathing fresh life into modern interpretations of Irish mythology. These works of modern Celticism remove themselves from the drab classical public domain art most are familiar with and drench themselves in a new aesthetic that I hope inspires more artists and storytellers to emulate and build upon.

Closing Remarks

Despite my criticisms that I have outlined here so far (and the ones in my forthcoming review) I highly recommend Hound to any fan of Irish mythological sagas and dark fantasy. Celtic-themed media is few and far between, but this graphic novel is a great addition to popular culture and I hope other artists and storytellers use Hound as an example to inspire and improve upon for years to come. It was a pleasure getting to read Bolger’s passion project so close after completing my thesis for Celtic Studies, based on the very mythologies I researched.

Newcomers to Irish mythology and Celtic studies will be especially amazed by this story, for the artwork and the concepts and characters presented from a different mythology from the more popular cultures (e.g. Greek and Norse). Celticists like me might be reading Hound with a grain of salt, but I’d rather rejoice in what Hound does brilliantly rather than dwell on the things that nagged my critical mind (even if that might not seem like the case in my scholarly review). Simply put, we need more adaptations of Irish (and other Celtic) stories, not necessarily to “update” them with modern values and agendas, but to reinvigorate interest in these overlooked cultures and mythologies. Hound is a great start, but I am also looking forward to what other projects may come that bring Celticism out of the stereotypes we’ve come to expect and into fresher—mayhap more accurate—territories of art based on myth.

Thank you for reading!

This has been my first, general review of Hound by Paul J. Bolger, and my first review on Senchas Claideb! Please leave a like and comment on this post, especially if you’ve read Hound yourself and give your thoughts on this epic adaptation, and spread the lore using the button directly below:

Also, if you know a friend who enjoys Celtic-themed, dark fantasy stories, refer them to Senchas Claideb using the “refer a friend” button below and receive access to rewards such as custom Gaelic phrases and an original short story!

Also, tune in this Friday (September 29th) to read my latest short story “The Phantom Hill”! You can read a sneak peek of it here!

Irish stories found in manuscripts from the medieval period are commonly divided into four “cycles” — The Mythological Cycle, The Ulster Cycle, The Fenian Cycle, and The Historical Cycle. The Ulster Cycle contains stories centered around heroes and events in the northern province of Ulster, the stories of Cú Chulainn are the most well known in this cycle.

I will be talking about this in more detail in my scholarly review, but there are a lot of Anglicizations of names that I found odd in Hound, Cú Chulainn’s being one of them. In the original Irish, his name is spelt as Cú Chulainn, but in Hound it is changed to Cú Cullan. Aside from ease of reading, I’m not sure what Bolger’s intention was for these changes as many of them also line up more closely with modern Irish pronunciations rather than medieval Gaelic.

I like the breaking up of the review. The art does look impressive, and I like stories that know how to have and prioritize properly emotional moments. Not familiar with Irish mythology so I'll likely learn quite a bit from the faithfulness review.

Excellent, thorough review! The art itself looks quite lovely, though I'm not sure how I feel about it only being in black, white, and red. Gives me callbacks to Dynamite Comics' Red Sonja. I feel like since this is an Irish myth there should be a lot more color, like emerald green for the landscape and bright cerulean for the sky. Ireland is colorful and lush! Feels like a missed opportunity, especially since it sounds like this adaptation is marketed towards a younger audience.

Sorry, rambled there for a bit. Other than my gripe with the color scheme, I'm really digging the art style and am curious to check this out for myself. Next time I'm down in Milwaukie I'll head into Dark Horse Comics and see if I can pick up a copy. I always love seeing reviews of obscure books/media, these creators deserve a chance of recognition. Looking forward to seeing your scholarly analysis of the tale!