One of the very first things I’m asked as a Celticist is what “Celtic” means. My own explanation would warrant a post by itself, but for the purposes of this one I’ll focus on how a “Celtic” flavor can be applied to horror—not only that but how to practically use it in writing and other artistic projects. In short, “Celtic” refers to a specific language family, under which are the Celtic languages, the current ones spoken being Irish, Scottish Gaelic, Manx, Welsh, Cornish, and Breton. The people who speak these languages are most accurately considered “Celtic.”

The idea of horror is not so far removed from world mythologies, folklore, and even historical fact. Humans are capable of horrific things just as well as the monsters brought to life by traditional stories, who are likely manifestations of human anxieties and tabus. The mythologies, folklore, and histories of Celtic-speaking peoples are ripe with themes and seeds for horror fiction. The Gaels of Ireland and Scotland, in fact, have some claim to the origins of Halloween with their ancient festival of Samhain (pronounced Sah-when). In medieval Irish literature and Gaelic folklore from Ireland, Scotland, and the Isle of Man, the night of Samhain (or Halloween or October 31st) is considered a time when spirits and demons are present in the world of the living. The 10th century Irish tale Echtra Nerai (“The Adventures of Nera”) says the following concerning Samhain or Halloween:

Great was the darkness of that night [Samhain] and its horror, and demons would appear on that night always.1

The protagonist of the tale, Nera, encounters the living corpse of a hanged man as he leaves the safety of the fortress of Cruachan. It is not explained how this man is returns to life but it might be the case that his soul was unable to pass into the afterlife; a medieval Irish audience was likely aware of the supernatural occurrences during Samhain. Aside from suddenly springing back to life, however, nothing more horrific transpires with this corpse.

Nera’s encounter with the corpse does remind me of an episode in “The Boyhood Deeds of Cú Chulainn” when he searches a battlefield2 for his uncle Conchobar, king of Ulster, following a harrowing battle. Cú Chulainn, armed only with his playing stick, encounters a pair of phantoms (called an airdrecht):

He saw in front of him a man with half a head carrying the half of another man on his back.3

The phantom with half a head becomes hostile when Cú Chulainn refuses to assist him, throwing the mangled corpse he is carrying on top of the boy-hero. Cú Chulainn retaliates by decapitating the phantom with his playing stick, seemingly killing him for good. Although we normally think of phantoms as incorporeal, it’s likely the medieval Irish had a different creature in mind when using the word airdrecht if such “phantoms” could be harmed by simple playing sticks.4 What is also interesting is that this encounter is not specified to occur on Samhain, but a badb is present as well. A badb is a scald-crow that is a form Irish war-goddesses could appear in, and her presence on the battlefield naturally indicates the abundant violence and death are part of her divine function. She also instigates violence by taunting Cú Chulainn:

“Poor stuff to make a warrior is he who is overthrown by phantoms!” Whereupon Cú Chulainn rose to his feet, and, striking off his opponent's head with his hurley, he began to drive the head like a ball before him across the plain.5

What we find in this episode is that battlefields in general might also be ripe grounds for horror or general supernatural happenings. With a countries whose history is as bloody and violent as Ireland and Scotland’s, even long past the Christianization period, there is potential for phantoms and old goddesses to emerge from the strife. Not every mortal who comes upon them may be as lucky as Cú Chulainn.

The episodes from Echtra Nerai and “The Boyhood Deeds” also share the quality that they are outside civilization. This goes into the broader concept of Celtic beliefs (or really most universal beliefs) in where supernatural events occur. Traditional Gaelic belief points to an Otherworld that is occupied by creatures the anglosphere would label as faeries, elves, and spirits. It is not exactly clear if spirits of the dead are known to occupy this space if they cannot find rest in Heaven or condemnation in Hell, but like most otherworldly beings they are also active on Samhain or in places and situations removed from society. Supernatural events and creatures in Gaelic folklore and mythology are most likely to manifest in spaces which can include the wilderness, darkness, twilight, mist, on water, underwater or underground, and even while sleeping (i.e. in dreams). Not only are these locations or conditions “thresholds” into the world of the supernatural, but they are prime, evocative settings for horror or dark fantasy stories.

When Celticists examine supernatural events occurring in the wilderness, we almost immediately think of the Fíanna and the legendary Irish hero Fionn Mac Cumhaill (also anglicized as Fin McCool). The Fíanna in Gaelic literature and folklore are semi-nomadic groups of hunters, warriors, and poets who live on the fringes of society—they warrant their own post as well, but it is still worth mentioning that they are extremely popular and integral to Gaelic storytelling and culture. One of their stories that stands out as a particularly interesting horror scenario is from the late medieval text Duanaire Finn (“The Book of the Lays of Finn”) and is titled “The Headless Phantoms.” Finn, his son Oisín, and the rest of his warband are guests to a crazy, ax-wielding churl6 able to raise and command nine headless corpses whose decapitated heads sing a horrendous chorus of shrieks:

The song they sang for us would have wakened dead men out of the clay : it well-night split the bones of our heads : it was not a melodious chorus.7

The churl kills the warband’s horses and tries to feed them their steeds’ meat. When they refuse, he and his undead minions attack the unwilling guests who must survive until dawn. This story alone has the makings of an archetypal “survive the night” horror story akin to something like Aliens (1986), Dog Soldiers (2002), or Predator (1987) complete with a band of hardened warriors fighting otherworldly threats.

Less martial-intensive stories and traditions concerning supernatural horror are also plentiful in Gaelic folklore. For example, the Fairies (Good People, The Boys, or any of the other names they are known by) operate on different logic than humans, with some of their tricks being cruel or downright malicious if it serves to entertain them or remedy a slight against them. One image that stands out to me from a short tale is a man from the fairy mounds roasting a human corpse on a spit along the roadside; the hapless traveller he asks to turn the spit for him soon realizes the corpse is still living and is scared senseless.

The locations of these otherworldly encounters also play into what little historical evidence we have concerning the pre-Christian belief system of Celtic-speaking peoples. Subterranean or chthonic areas such as underground (or under hills, specifically) or underwater may have been considered access points to the Otherworld and are where we find evidence of funerary rites and ritual offerings to deities. Entire hoards of treasure where thrown into lakes and rivers or even left out in open-air temples, but was let be for fear of falling victim to a curse. Arthur Machen and Robert E. Howard ran with ideas of fairy mounds in Ireland, Scotland, and Britain being host to prehistoric peoples who devolved over the years into pale, child-thieving monsters. Most famously—and relevant to this post—there are also the “Bog Bodies,” which are naturally preserved mummies. Mummies such as the Tollund Man, Weerdinge Men, and Old Croghan Man have evidence of ritual sacrifice or execution methods; the exact purposes or functions of these sacrifices are unknown to historians but ripe ground for writers to imagine what primordial powers these men were slain in the name of.

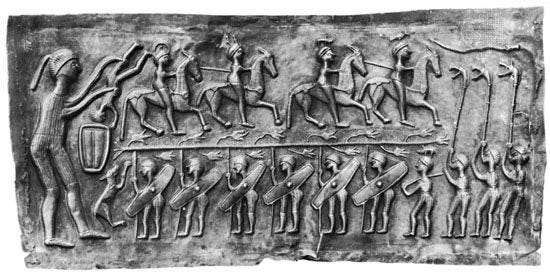

(Above: Panel from the Gundestrup Cauldron)

Truly this, in my opinion, is where the untapped potential of “Celtic” horror comes from. We know so little about the gods they worshipped other than that they manifested in nature and a single passing remark from a Roman observer that Celts visiting the city laughed at the idea of gods being portrayed as human-like. Although Romans painted Celts in a mostly negative light, there are still fragments of their propaganda that align with the more Lucan’s description of a sacred grove (called a Nemeton) is highly reminiscent of the police raid on the swamp cult in “The Call of Cthulhu”:

There was a grove, never violated during long ages, which with its knitted branches shut in the darkened air and the cold shade, the rays of sun being far removed. This no rustic Pans, and Fauns and Nymphs all-powerful in the groves, possessed, but sacred rites of Gods barbarous in their ceremonial, and elevations crowned with ruthless altars, and every tree was stained with human gore. If at all, antiquity, struck with awe at the Gods of heaven, has been deserving of belief, upon these branches, too, the birds of the air dread to perch, and the wild beasts to lie in caves; nor does any wind blow upon those groves, and lightnings hurled from the dense clouds; a shuddering in themselves prevails among the trees that spread forth their branches to no breezes. Besides, from black springs plenteous water falls, and the saddened images of the Gods are devoid of art, and stand unsightly formed from hewn trunks. The very mouldiness and paleness of the rotting wood now renders people stricken with awe: not thus do they dread the Deities consecrated with ordinary forms; so much does it add to the terror not to know what Gods they are in dread of. Fame, too, reported that full oft the hollow caverns roared amid the earthquake, and that yews that had fallen rose again, and that flames shone from a grove that did not burn, and that serpents embracing the oaks entwinned around them.

The people throng that place with no approaching worship, but have left it to the Gods. When Phoebus is in the mid sky, or dark night possesses the heavens, the priest himself dreads the approach, and is afraid to meet with the guardian of the grove.8

Untouched wilderness inhabited only by whatever supernatural “guardian” had occupied it since time immemorial. Even the very wind dares not disturb the branches of this primeval ground. The only evidence of supplication potentially being the remains of sacrifices spattered on the trees and stones. Although much of the world has been hewn, industrialized, and explored there are surely pockets which had been missed or which gods locked under prisons of concrete and metal would do anything to be released from their torture.

(Above: Sir Christopher Lee as Lord Summerisle in The Wicker Man [1973])

Although the human sacrifice aspect of the pre-Christian Celtic religion may have been exaggerated by Roman propaganda, there is still evidence (however scant) of it being practiced, as with the Bog Bodies mentioned above. The sacrifice methods of hanging, drowning, and burning in devices such as the Wicker Man are images that have entered popular culture already. Paired with the unknowable, mysterious gods these methods paint the picture of grim tribes using what means—no matter how dire or bloody—they can to keep the darkness at bay. Although the modern Celtic-speaking peoples are far removed from pagan peoples, primordial fears and beings still dwell in the night to prey on what poor souls—unwitting sacrifices—they can scrounge up in an age where Christ is King.

I have also written on the god Cromm Crúaich and my use of him in my story “The Tomb of Tigernmas”, found in DMR Books’ Samhain Sorceries (see this post for more information). Cromm remains an enigmatic deity as most depictions portray him as a big snake, although I cannot find any archeological or literary evidence to support this. In my opinion, it may be more interesting to view his domain of Mag Slécht as something like a nemeton, a sacred ground where he is the guardian with no clear manifestation other than a force of nature which occupies a grim, cyclopean idol erected by hands that might not have been human.

Before I end this post, I wanted to include an aside about my own possible brush with a creature from Scottish Gaelic folklore on Halloween. There is the belief among Gaels in two types of spirits that emerge on or around Halloween night—the spiorad-nam-bàs and the spiorad-nam-beò. A spiorad-nam-bàs is “a spirit of the dead”, which is a typical ghost and usually is trapped on Earth due to some unfulfilled business (e.g. an unsolved murder, something left behind, or a crucial message). These spirits are harmless and if asked what they want, they’ll respond. A spiorad-nam-beò (“spirit of the living”) is the apparition of a person who is alive but is restless in their own way, such as wanting to be somewhere else than where they are now. These spirits are hostile and will attack anyone who comes near them or tries to speak with them—so if you’re out on Halloween and see a person you know for a fact is supposed to be somewhere else, it’d be best to avoid them.

My experience comes when I was in Nova Scotia in my first year of graduate school. I was at my friends’ house for their Halloween party (on October 30th). The house was a raised bungalow with a set of stairs at the front door leading up to the living room. I was sitting near the top of the stairs leading down to the front door when it suddenly opened and a whole crowd of people shuffled in. One of my friends at the party was dressed like Cher and amid that crowd I spotted our other friend, a guy dressed like Sunny Bono—he was looking straight ahead with a blank expression on his face but I didn’t think much of it at the time. Later, I overhead my friend dressed as Cher mention that our friend—the Sunny impersonator—didn’t come to the party. When I was able to think through all the cider, I realized he in fact mysteriously vanished after that crowd of people I saw him in dispersed through the house. I didn’t bring up what I’d seen until a year later when I mentioned that “Sunny” must have bailed during the middle of the party, however both my friends confirmed he in fact did not come but was intending to go dressed as Sunny Bono. During my coursework that first year, I’d learnt about the two types of spirits and realized that I quite possibly saw our friend as a spiorad-nam-beò. When I brought this up to “Sunny” he mentioned that he had wanted to come to the party but got roped into last minute work obligations. You might wonder if this was too much cider, a trick of the light, or just an honest mistake. However, I choose to believe that I saw a spirit from Gaelic folklore in Nova Scotia—a place where Gaels brought their songs, stories, and ghosts—very close to Samhain’s Eve.

“Celtic” horror, like most things labelled “Celtic”, is difficult to summarize in a single breath. Although most of my post has examined the mystique and darkness of the ancient Celtic-speaking world, it is still possible to apply the horrors into modern day. Celtic-speakers still live today, and as such so do their stories, so it only makes sense that fearful things from their past can be frightening in the present. This idea of “Celtic” horror shouldn’t feel restricted by time periods, but place most certainly is a key factor—Celtic-speakers “haunt” places they’ve been with place-lore (dindshenchas) and these places become integral in their mapping of their own world. Like the wider world, there are dark corners, and what lurks in those dark corners could be older than anyone could ever guess.

Thanks for reading! Leave a like and comment your thoughts below! Has anything in this post inspired you to write a new story? Do you know of a scary story from a Celtic-speaking person? If so, feel free to share it!

Also, keep reading for this week’s Halloween recommendations!

Butterfly Kisses (2018): This “meta” found footage movie framed as a documentary follows a struggling film maker trying to simultaneously market and analyze a film he claims to have dug out of his in-laws’ basement. Said film is of a college student’s thesis inspecting a folkloric entity known as “Peeping Tom.” Although he claims the footage is genuine, he cannot find any proof of the people in the film actually existing or ever having gone missing. Butterfly Kisses mostly examines how art becomes an obsession and can even spread like a disease, almost like how the “Yellow Sign” from Robert W. Chambers’ The King in Yellow affects the minds of artists.

“The Idol of Cromm Cruac” from Hall of Fantasy: This short radio drama is a fun listen for people who want a small sampling of “Celtic” horror. There are inaccuracies abound in this tale, but it nonetheless has some nostalgic moments for those who grew up listening to classic radio.

Absentia (2011): I’ll be honest and say that I do not like Mike Flannagan’s recent Netflix series, however I will give him credit for his crowdfunded release Absentia. What Flannagan does best in this is making the mundane feel tense and foreboding. He sets it right in an unassuming suburban area, but seeds hints of horror early on and slowly unravels the plot (but not the mystery), leaving us in the dark until the very end where it is up to the audience to piece together what happened.

Photo by Thomas Despeyroux on Unsplash “The Dead Valley” by Ralph Adams Cram: A classic, short horror story, I recently came upon this while listening to the H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society’s The Literature of Lovecraft audiobook. It is a simple, yet chilling tale centered around a young boy in Sweden who chances upon a mysterious, frightening valley one night and tries to seek it out again despite the misfortune it brought him.

“The Man in the Black Suit” by Stephen King: If I had one chance to hook a new reader onto Stephen King or convince a King-denier that he’s actually a good writer, I’d recommend “The Man in the Black Suit.” This tale is what I have come to term as “The Essential King”—it is from the perspective of a young boy encountering a boogieman in the New England wilderness during a disconnected era of America—everything which makes Stephen King’s work his own and him at his best. I won’t say more on it since it is a gripping read and perfect in case you haven’t had a dose of King this Halloween season yet.

Thank you again for reading! Be sure to hit the button below to share this post and spread the lore!

Also, use the referral button below to refer a friend to Senchas Claideb and receive access to special rewards, including a customized Gaelic phrase and an original short story chockfull of Celtic horror.

Echtra Nerai: §2; translated by Kuno Meyer in Revue Celtique 10 (1889); Original Irish: Ba mor iarum a dorchotai na haidqi sin, ogus a grandatai, ogus doaidbitis demnoie ind oidqi sin dogres.

The original Irish dubs it as ármach which literally translates to “slaughter-field” (ár = “slaughter” + mag “field”). Although it is a small detail, it is an interesting thing to call battlefields in this period.

Táin Bó Cúlainge (Recension 1), translated by Cecile O’Rahilly; Original Irish: Co n-acca ara chind in fer & leth a chind fair & leth fir aile fora muin.

Cú Chulainn’s superior strength might also have aided him in fighting his supernatural foe; he also can be considered a demi-god thanks to one of his incarnations being sired by the god Lugh. It is also worth mentioning that the second recension of the Táin Bó Cúailnge states Cú Chulainn’s playing stick is made of bronze, however, I am not aware of bronze having the trait of damaging supernatural entities in medieval Irish belief.

Táin Bó Cúailnge (Recension 1), translated by Cecile O’Rahilly; Original Irish: “Olc damnae laích fil and fo chossaib aurddrag!” La sodain fónérig Cú Chulaind & benaid a chend de cosind luirg áne & gabaid immáin líathráite ríam dar in mag.

There is also an aside that implies this churl has only one eye which is usually an indicator of someone having otherworldly knowledge or powers.

Duanaire Finn: XIII.30 translated by Eoin MacNeill and Gerard Murphy; Original Irish:

Lucan, Pharsalia, translated by H.T. Riley: 112-3.

Celtic lands and Celtic culture certainly give us both beauty and foreboding - simultaneously. On our recent trip to Cornwall, we were astonished by the beauty of the rugged coastline as we trod the southwest coastal path. On the return leg of our walk, the mist quickly rolled in and transformed the same landscape into an otherworldly scene. It’s no wonder that so many stories have been inspired by the Celts.

Also, it’s “Sonny” Bono of Sonny and Cher fame.

You have certainly given your audience a plethora of choices for spooky stories to read on Halloween!